DOCS AT THE 2011 URBAN WORLD FESTIVAL

When historical documentaries spotlight the dynamic past, they also reveal, if one is prone to see, an uncomfortable present. This can fuel nostalgia and a yearning to return to that great by-gone era just witnessed on the screen. While making you feel good about the past, docs can make you feel lousy about today. After watching the premier Brooklyn Boheme, and listening to the Q&A afterwards, a lot of us felt lousy about today.

For some 15 years in the 1980s and 1990s, Fort Green and to a lesser extent neighboring Clinton Hill were home to an extraordinary community of Black and Hispanic artists. In the film we hear from former and current residents, including filmmaker Spike Lee, actress Rosie Perez, jazzman Bradford Marsalis, comedian and actor Chris Rock, and rock guitarist Vernon Reid. Spike Lee calls this time “the Brooklyn equivalent of the Harlem Renaissance.”

While the Harlem movement was limited to literature and jazz, the Brooklyn bohemian community was broader, including performance artists, filmmakers, comedians, and visual artists. Both, however, were rich in African-American and Hispanic talent, both were a synergy of artists and community, and both — one before the Civil Rights Era and the other after — left strong historical imprints.

Filmmaker Nelson George, who still lives in Fort Green, presents an intimate portrait of an exciting place at a creative time. The film begins in the 1970s when the neighborhood is impoverished and riddled with crime, yet also cheap to live in, followed by the 1980s and 1990s with the incredible creative explosion, and finally the gentrification of the neighborhood that has resulted in an exodus of artists.

Told by those who lived there and participated in its artistic community, Brooklyn Boheme presents a gripping story with the voice of authenticity. While a similar artistic gathering occurred at roughly the same time in downtown Manhattan (mostly white and documented in numerous films), the story of this once dynamic African-American community across the East River in Brooklyn is much less known. Brooklyn Boheme fills an important gap in the history of American bohemia and does it extraordinarily well.

When film festivals begin to look and feel too similar, and you’re bumping into the same films too often, Urban World Film Festival on 34th Street in New York City is a great antidote. Heavily African-American (the audience, the filmmakers, the film subjects) the festival also travels the globe with films from and about Africa, the Middle East, India, and the Philippines.

“Our goal is to be a platform for multi-cultural filmmakers,” says Gabrielle Glore, the executive director of Urban World Film Festival. “We want films by and about people of color, but more important than race is an urban sensibility.”

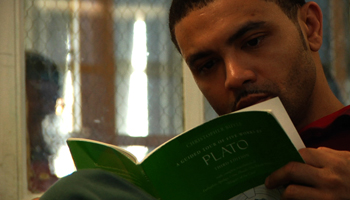

Zero Percent (pictured top) is, except for one Chinese-American, also about a group of African-Americans and Hispanics. They’re significantly different, however, from the “Black Nerd” artists of the Brooklyn Renaissance. For one thing, they don’t have to worry about gentrification. Their neighborhood is surrounded by very high walls.

Although there are many films about prison life, probably too many, that is beside the point for Zero Percent. This prison doc is simply riveting.

With extensive access to the notorious Sing Sing Correctional Facility, director Tim Skousen tells the story of the transformation of a group of inmates. The catalyst for their change is a desire for education. The vehicle is a rigorous college education program run by the nonprofit Hudson Link organization (the prison sits on the banks of the Hudson River) in partnership with Mercy College. The inmate-students are middle-age men serving long prison sentences, many for more than 20 years for murder. At the same time, the men are inquisitive, highly motivated, and well prepared for class — students that would make the typical American college teacher drool with envy.

In the prison’s school the men are engaging and articulate, expressing their thoughts and opinions with force and self-confidence. Outside class they confront their horrible crimes and envision themselves as honorable men. Captured on camera are the men’s tears, their self-doubts, their dreams, their pain, and their shame. Then comes graduation day, and the college diploma becomes proof that they are now worthy of being honorable men. It’s very moving.

Over the years, our educational and correctional communities spawned many experts pushing grandiose plans that quickly ended up as failed experiments. With little faith in reforming our schools, the substitute became more standardized testing; with little faith in rehabilitating inmates, the alternative became longer incarcerations. Yet, the recidivism rate today for released prisoners in the United States is a whopping 60 percent. This is dangerous and expensive for society. Meanwhile, for the 46 released inmates who have graduated from the Hudson Link/Mercy College program, their recidivism rate is zero.

Zero Percent is an honest, exhilarating documentary with an important message, one that this nation would be wise to examine.

In Brooklyn Boheme a community inspired a diversity of individual artists to innovate and create, and in Zero Percent a college education program was a critical tool to remake men who had committed horrible crimes. Now in my third doc, The Start of Dreams, art is not an end but a means. And the goal is not to remake damaged prisoners but for high school kids to understand themselves.

The Start of Dreams, directed by the Horne Brothers of Atlanta, is organized around African-American Broadway director Kenny Leon and his effort to counter the expanding cultural void in America. What galvanized the award-winning director was the growing public belief that art education is expendable — the first program to be cut, the last program to be reinstated. So Kenny Leon formed the August Wilson Monologue competition for minority high schools students with winners from various regional events brought to perform on the New York stage.

Although the documentary is about winning and losing, experiencing success and coping with failure, on a deeper level, as one young female participate says, it’s about “finding ourself.” The monologue competition is about bringing a new generation of African-Americans into the theater and making America a better nation, but more it’s about bringing a new generation of African-Americans to themselves and this will make America a better nation.

As students deliver heart wrenching and forceful monologues, interwoven are notables — Samuel L. Jackson, Denzel Washington, Phylicia Rashad, Anthony Machie and of course Kenny Leon — who pound away on art being a necessity, not a luxury. Art feeds the human soul. Art expands the creative mind. Art is critical for our struggling country. Art is essential for our children who will inherent our struggling country.

The Start of Dreams is a delightful film that moves the heart as it probes the mind. While entertaining, the film is thought-provoking. While encouraging the dreams of youth, it demands America nurture these dreams. While our nation moves away from the arts — Kansas being the first state to end funding for the arts — The Start of Dreams is not only informative but extremely timely.

After a few years on the circuit, film festivals tend to be relatively simple to categorize. Their film programs run from highly eexperimental to cinephile esoteric to mass accessible to thematic focused to genre specific. Urban World, with its “urban sensibility,” is not easy to categorize. Executive Director Glore elaborates: “The urban is not only Black and Latino, which many people think it is, and not just [about] ethnicity — urban is a sensibility with geography and energy and grit. It’s edgy.”

The urban doesn’t necessarily have different concerns, but there are different emphases. The rainbow of themes is not the same, which means the experience is different. The people are somewhat different, but race is always a shallow indication of that, but discussions are somewhat different. This is what diversity is about. Although an easy word to say, diversity, it is an increasing difficult concept to keep alive in our age of spreading homogeneity. But it’s sure alive at the Urban World Film Festival.

And right now I’m trying to decide on seeing either a film about gentle Filipino teachers in rough Baltimore or a film on modern urban Indian women seeking traditional arranged marriages. There is nothing simple about the urban sensibility.