Back to selection

Back to selection

EASTERN PROMISES, WESTERN AVOWALS: THE NEW YORK FILM FESTIVAL (PART TWO)

That undefinable thing called texture: It is a principal difference between cinematographic imagery from West and East. For starters, take a look at the wall show of French celebrity photos in the Walter Reade Theater’s Roy Furman Gallery, faces and torsos foregrounded with little or no regard for light or materials, and complete disregard for context. Then take a look at the stills pictured here from the four films reviewed below.

That undefinable thing called texture: It is a principal difference between cinematographic imagery from West and East. For starters, take a look at the wall show of French celebrity photos in the Walter Reade Theater’s Roy Furman Gallery, faces and torsos foregrounded with little or no regard for light or materials, and complete disregard for context. Then take a look at the stills pictured here from the four films reviewed below.

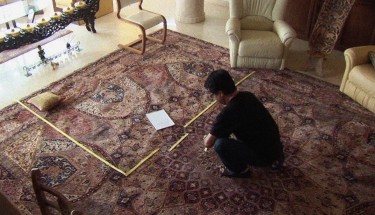

In the Canadian/British A Dangerous Method, by David Cronenberg, and the American Sean Durkin’s Martha Marcy May Marlene, they are basically head shots, not particularly interesting, and they tell you little about the narrative they are supposed to be emblematic of. On the other hand, the still from Iranian filmmakers Jafar Panahi and Mojtaba Mirtahmasb’s This Is Not a Film (pictured, right) is a microcosm of the movie’s topic (creating while banned from doing so) and tone (desperation); and the one from Turkish director Nuri Bilge Ceylan’s Once Upon a Time in Anatolia is a slice, a cross-section, of a serious, moody film in which details such as lighting and composition provide as much or more information than exposition about characters, their baggage, and their relationships.

A lesson in the varying weight of, and respect for, the senses in Western and Eastern visual styles is right there in some of the diverse elements that make up this edition of the NYFF. Like the gallic celeb snaps (selling point: legends caught casual), the stills from A Dangerous Method and Martha Marcy May Marlene (fully posed, with approvals by publicists et al de rigeuer) also say a lot about star power in the West. Yet in the photo from This Is Not a Film, an unadorned Panahi squats on his living-room floor trying to work and explain, while in the image from Once Upon a Time in Anatolia, the performers are not even recognizable: Their have their backs to the camera.

All of the films reviewed here have few principal characters, and not many supporting ones. Can the comparison of stills East and West serve as some sort of model by which to evaluate the full-length features? I hypothesize that yes, the lack of bodies, as well as props, does not affect the organic nature of the Turkish and Iranian films; the American and Canadian/British movies, however, feel lacking, in very different ways. High costs are, of course, a major factor in the American indie scene, its films frequently appearing underpopulated, no matter what the filmmaker and crew do to make up for it. The Canadian/British is a different story: It is as enervated as the still on display here.

The third and final installment of my coverage of the NYFF appears later this week.

Wind From the East

An Effort, as the credits put it, by Iranian filmmakers Panahi (The Circle, The White Balloon) and Mirtahmasb (Good Bye) to simulate a real movie around the directing constraints placed upon the former by Iranian authorities, the very special This Is Not a Film succeeds in its mission. In the process, it becomes without intention an excellent master class for the viewer. (Now under house arrest and awaiting a final decision on his fate, he is banned from directing for up to 20 years and could serve up to six years in prison.)

He deconstructs for Mirtahmasb the execution of the film he has been planning to make from his own screenplay. He translates what might otherwise have been storyboards and continuity notes into verbal descriptions of images and action, even using tape on the living-room floor of his luxurious high-rise apartment to outline sets and elaborate upon scenes in a two-dimensional approximation of the phantom third. Ironically, the plot anticipates his own destiny: Religious parents lock up their daughter in their home in order to prevent her from attending university.

It breaks the heart to observe Panahi’s sullen face while he receives on the phone pessimistic updates on his legal prospects. He kills time, playing with his daughter’s giant pet iguana or just moping on the couch. But once he shifts into a filmmaking mindset, his juices get going and he makes the most of the restrictions. He shoots exteriors from his balcony, and, for vertical variety, films in the building’s elevator the boy who takes out the garbage. In spite of these transgressions–camera work could be defined as a subset of directing—set-ups for the static shots inside his apartment were set up in advance by his son. Somehow, they have a compositional elegance that comes natural to the father.

Livia Bloom wrote in Filmmaker that Mirtahmasb said that during the shooting of the film, Panahi was in fact allowed to go outside, anywhere within Iranian borders, in fact. Assuming this to be true, you might ask, Is this a what-if situation, a film shot in subjunctive mode?

Turkish director Ceylan has struck gold with Once Upon a Time in Anatolia, one of his best films, which has an extended nocturnal first 90 minutes that are too languorous for many. There is a payoff: They are rich in providing details that help define characters in the remaining, brightly lit hour. (A sublime late-night meal at a village mayor’s house divides the film in two.)

The storyline is simple: A caravan comprised of, among others, the local police chief, his driver, a staffer, a doctor, several laborers, two suspected killers, and a prosecutor from Ankara moves from one site to another on the southern Anatolian plains in a near-futile attempt to uncover the corpse of the murder victim. The chief perp either lies or can not remember the exact spot where he buried the man, in what may have been a feud over his unfortunate man’s young widow and the paternity of her son. The real goal for the authorities is to complete a required, anachronistic bureaucratic report.

All of the men have issues, merely hinted at here and there. (Their interaction reeks of a combo of male fraternity and rigid hierarchy.) The chief of police has a son with seemingly severe problems he has so much trouble dealing with that he stays away from home as much as possible. The prosecutor repeats over and over to the doctor a supposedly hypothetical case of a woman who timed her own death after childbirth to punish her husband for infidelity. The young, handsome doctor ends up being the most mysterious: He has a stone face, tells us his story with glances, and even falsifies an autopsy report on the dead man (who was hog-tied and possibly buried alive). We are never sure what his connection to the dead man and his wife might be; we can only speculate.

Ceylan is a master of lighting, of landscapes of nature and the human face. The flow of the narrative is never rapid or rushed: It is a slow tide that gives you time to meditate on every scene.

Go West!

Kudos to director Sean Durkin and editor Zac Stuart-Pontier: I’ve rarely seen such smooth editing between different time periods as in Martha Marcy May Marlene. It is incumbent upon them to make it work, in order to maintain a chilling effect throughout, in this profile of a mentally disturbed young woman. She has fled from a twisted farming commune in upstate New York, a collection of pod people under the abusive supervision of a Mansen-like patriarch, Patrick (John Hawkes), and takes refuge with her straight-arrow, haute bourgeoise older sister and her banker husband in suburban Connecticut.

Martha, aka Marcy May or Marlene at the commune, is played by Elizabeth Olsen fairly well, except that her expressions don’t change much between one location and the other. Either her repertoire of gestures is limited, or a problem with Durkin’s screenplay prevents her from signalling much information. She never explains herself or her actions, although one shockingly violent flashback of an episode in which the commune dwellers rob a house informs us what had been her breaking point. Olsen has been lauded for this role, but I found it difficult to care much for this lost character without a persona.

We know little about her, except that her sister, Lucy (Sarah Paulson), is her only surviving family member, the two did not have a close relationship, and that they come from some kind of troubled home. Martha cracks a couple of times, but that’s about as far as she gets from a vague blankness throughout. Lucy’s goal-oriented husband, Ted (Hugh Dancy), has a low threshold of tolerance for his directionless sister-in-law and just wants her out.

Saunder Jurriaans and Danny Bensi’s music, often simply ominously long chords, adds to the atmosphere of disorientation, for Martha and for us, helping to keep the film within the generic boundaries of a psychological thriller. The antipodes of Martha’s residences, though, are too pat, so that sometimes sound and montage feel compensatory. We’ve seen the clone-like commune dwellers and their leader before, and Lucy and Ted’s sprawling house and pool are reminiscent of many imposing residences in Hollywood pictures over the years. Durkin’s direction is praiseworthy, but this good film could have been better if he had blurred the distinctions a little more.

If you go to see A Dangerous Method under the assumption that it is, somehow, Cronenbergian (violence, creatures, grittiness, etc.), you’d best reconsider. This is a case study in lacquered Europudding, as stagnant as the waters of Lake Constance, where some of the encounters take place. Unlike Martha Marcy May Marlene, everything—walls and floors, clothes and skin, Victorian-era phonographs and bric-a-brac—feels squeaky clean, as is often the case with internationally funded coproductions. The term texture is hardly operative.

A voice coach committed to ensemble playing might have been a plus: There is no consistency of accents. Of the principals, only Keira Knightley’s Sabina Spielrein, a Jewish émigré from Russia to the twin settings of Switzerland and Austria, attempts to speak with a native accent. She does a poor job of it, but it comes off worse for the fact that the Swiss Carl Jung (Michael Fassbender) and the Austrian Sigmund Freud (Viggo Mortensen) have no Germanic inflection to their words: They speak British English. Masterpiece Theater English. Then suddenly a character like the director of the Swiss hospital where Jung practices and to which Spielrein has been committed comes out with thick German more Hogan’s Heroes than echt teutonic.

The stagnancy of dialogue and action could stem from the film’s theatrical roots: It is based on the play The Talking Cure, by Christopher Hampton, who also wrote the screenplay. Words like transference and counter-transference are thrown about as in a Psych 101 class.

There are two saving graces: One is Mortensen, who does not gesticulate unnecessarily like Knightley (she gobbles up the scenery—it’s the worst performance I’ve seen all year–whether she’s in hysterical feral mode at the beginning or speaking to Freud and Jung as a trained psycholanalyst merely a few years later), yet he is never wooden, like Fassbender. With only a bare movement of his mouth or a puff on his cigar, Mortensen’s Freud feels like a real person.

The other is Vincent Kassel as their colleague Otto Gross, the one welcome smudge on the glossy film. A self-assured cocaine addict and sexual obsessive with no regard for convention, his character’s wild, chaotic nature comes through, as if a tourniquet has been removed from the narrative flow.

You can look at the film as a construct: Freud = superego; Jung = ego; Gross and Spielrein = id. Another dynamic is the zigzag father-son relationship between Freud and Jung, which is much more credible than the affair between Jung and Spielrein, no matter how much he spanks her, or the frozen obligatory rapport between Jung and his wealthy wife, whom he treats more like a breeding machine than a real person.