Back to selection

Back to selection

The Microbudget Conversation

We're Only Talking a Few Thousand Dollars by John Yost

The Microbudget Conversation: Form And Content

As we wind down “Season One” of the conversation we take a look back and discuss what might have been overlooked. When I first started this column my hope was that filmmakers and tastemakers would use this forum as a way to debate, raise questions, and challenge one another. For the most part I’ve been happy with the subjects raised by this column and the subsequent conversation that has started in the comments section of some of the posts. However, as we push forward in the new year I would like if we didn’t just talk at you, but with you. We will still use this as a place to raise questions and to present a topic, but I would love it if we were to add more of an answer to the question, or a thread of discussion outside of the comments section. Perfect example…today’s post. Alex Barrett is a filmmaker from the U.K. and one of our avid readers. His entry is a perfect example of a well thought-out response to the “questions” we’ve been asking, and the future of this column.

When I started thinking about ideas for this article, the first thing that occurred to me was the use of the word ‘conversation’ in the series title. Assuming it to be carefully chosen, I decided that rather than writing my piece in a vacuum – and therefore creating a monologue – I’d go back through some of the previous articles in the hope that they might spark something closer to the start of a dialogue. Many interesting points have been covered, and I wanted to use my response to them as the seeds for discussing my own ideas of filmmaking – ideas shaped while working on my microbudget debut feature, Life Just Is.

Going through the articles, I was struck by Nicole Elmer’s piece on Script v. Story, which promotes a mode of microbudget filmmaking that eschews traditional scriptwriting in favor of capturing “magical moments” brought about through improvisation. Elmer’s argument appears to be that filmmakers often “forever tweak scripts for which they keep trying to raise money” rather than simply making films, and that even seemingly simple scripted scenes inflate budgets by requiring “resources that must be pulled together for this completely fabricated event.” Her point is well argued and articulately put across, but I still can’t help but disagree with it, especially given my experiences, and my intentions, when making Life Just Is.

I’d like to clearly state that I’ve never met Nicole Elmer, and that based on what I’ve read, I have nothing but respect for her. My purpose is in no way to debase her argument, but merely to offer some contrasting views in the interest of opening up debate. Also, inasmuch as Elmer is keen to point out that she still loves scripts, I’m equally keen to say that I’m in no way against improvisation or the type of filmmaking she’s advocating. Many good films have been made, and will continue to be made, that way, and it was filmmakers like Joe Swanberg who inspired me to actually go out and make films. My point is simply that I believe that working from scripted material offers a range of benefits not offered by a more improvisational approach.

The first benefit admittedly stretches beyond the microbudget conversation and into more general filmmaking conversations, but that certainly doesn’t mean that those working on low/no budgets shouldn’t be taking it into consideration. As my Executive Producer, Christine Hartland, has said to me: whatever the scale of your film, your budget isn’t the most important thing. Telling a good story, conveying your ideas and connecting with the audience all take precedence. So, in this sense, making a microbudget feature is no different from making a multimillion pound feature (and there’s no reason why low funds should prevent you from running your production in a professional manner). More to the point, if you want to make a film which is going to find an audience, however limited or niche, you need to think about what’s going to make it different and what’s going to make it connect. I’m not necessarily talking about putting your audience first (filmmaking is, and should be, as much a mode of personal expression as any other art form), but about finding a way to convey that personal expression to an audience so that it makes sense. To put it another way: I’m talking about taking your abstract ideas and turning them into physical form.

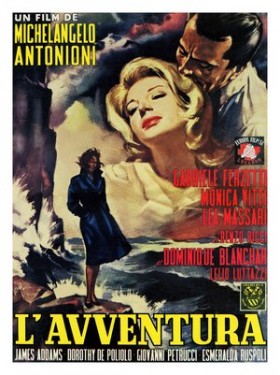

Moving beyond this we come to what I’ve grown to believe is the highest form of cinematic expression: a synthesis of form and content. As an art form, film is almost all-encompassing, including as it does a wide range of disparate audiovisual elements. To arrive at its purest form of perfection, then, all these elements should come together in a mutually cohesive whole, each one working to support and enhance one another, while all striving towards to same goal. Lest this become too abstract, I’ll give you an example:

Michelangelo Antonioni’s 1960 film L’Avventura concerns the sudden disappearance of Anna and the subsequent hunt to find her by her lover Sandro. The moment Anna disappears is conveyed as such: Anna and Sandro are standing on a small island, arguing. He crosses from screen right to screen left, the camera following his movement, taking Anna from screen left to screen right. The image of the lovers dissolves into an establishing shot of the island, which places a cliff-face on the left of frame and the sea on the right. The framing of these two shots, along with the dissolve itself, means that Anna fades into the sea while Sandro fades into the island. A small boat crosses from left to right, heading away from the island (and thus Sandro). This, we can assume, is Anna making her escape. The soundtrack is sparse, the noise of the waves all-consuming. Thus, in one simple dissolve Antonioni has shown how Anna has made her escape and left Sandro behind on the island: story and filmmaking have become one, and a complete synthesis of form and content has been achieved.

Michelangelo Antonioni’s 1960 film L’Avventura concerns the sudden disappearance of Anna and the subsequent hunt to find her by her lover Sandro. The moment Anna disappears is conveyed as such: Anna and Sandro are standing on a small island, arguing. He crosses from screen right to screen left, the camera following his movement, taking Anna from screen left to screen right. The image of the lovers dissolves into an establishing shot of the island, which places a cliff-face on the left of frame and the sea on the right. The framing of these two shots, along with the dissolve itself, means that Anna fades into the sea while Sandro fades into the island. A small boat crosses from left to right, heading away from the island (and thus Sandro). This, we can assume, is Anna making her escape. The soundtrack is sparse, the noise of the waves all-consuming. Thus, in one simple dissolve Antonioni has shown how Anna has made her escape and left Sandro behind on the island: story and filmmaking have become one, and a complete synthesis of form and content has been achieved.

Now, at this point I have to be honest and say that I don’t know how Antonioni created this moment: I don’t know whether it was planned in advance, or whether it was a happy accident discovered in the edit room. Perhaps it was even the simple result of genuine innate genius. It’s certainly true that it makes synthesizing form and content seem deceptively simple when, in reality, only the greatest filmmakers manage to pull it off with any level of consistency. But if, as I believe, this is what ultimately represents the greatest use of the cinematic medium, surely it’s something that we should all be working towards, despite its difficulty.

So, if a synthesis of form and content becomes our aim, one clear question arises: how can it be achieved if we don’t know in advance what our content actually is? This, then, is where – for me – scripting and pre-planning become essential parts of the filmmaking process: surely taking the time to think things through and figure out the best way to achieve that perfect blend, in advance of the pressures of the shoot, is a good thing? It’s also worth remembering that, although it does take time, planning doesn’t cost anything. Thinking is free. So no matter how small your budget is, it still shouldn’t prevent you from being able to think your film through in advance.

It’s probably important for the sake of clarity to state that I’m not talking about planning a film to the extent that all life and spontaneity is completely crushed from it. I’m talking about solid planning, not rigid planning: it’s an important distinction. Even on a scripted film shot in a controlled environment, elements of chance and inspiration will come into play. That’s simply part of the filmmaking process, and a part that should be embraced. It’s also worth remembering that, even when working from scripted material within a story-boarded frame, your actors will bring a whole other level of unexpected magic to your material. For instance, there’s a moment in Life Just Is when one of the characters is upset. Her flatmate notices, and goes to stroke her arm consolingly. But as she does so, she picks a hair off her shoulder first. To me, the picking of the hair is a magical, spontaneous moment, and while neither my script nor my storyboards planned it, they also didn’t prevent it. A more significant example, perhaps, is a scene where a character was supposed to exit the room and then re-enter at the end. On the day, the actor suggested that it would be better if he stayed out of the room, thus shifting the focus of the scene’s ending onto the two characters left in the room. It worked brilliantly. Planning doesn’t have to kill spontaneity. But, to quote Christine again, you can’t move on to Plan B if you don’t have a Plan A. If you get on set without a plan and inspiration doesn’t strike, you’re either going to be wasting a lot of time waiting for it to come or, more likely, you’re just going to make something flat and uninteresting.

So, while it’s true that, if the planets align and the magic comes at the right moment, you could end up with something brilliant – perhaps something even better than anything you’d have been able to plan in advance – I ask: why take the risk? Filmmaking is hard work. Bloody hard work. There’s never any guarantee that the film you make will come together as you want it to or that all the elements will click into place. So why take a chance on finding it as you go? If you have a script and a proper plan, you’re not cheating. You’re giving yourself a fighting chance.

Elmer is certainly correct to caution against toiling away for years and years trying to perfect your script, but in the words of Stanley Kubrick: “don’t you want to get it right?” Elmer herself states, “Artists only improve by continually working on their craft,” but to me this is as much an argument for redrafting screenplays as it is for getting out there and shooting your film. In the cut-throat world of filmmaking, you are only ever as good as your last project, and if you don’t take the time to get it right, what’s the point in making it at all? Of course, mindless perfectionism isn’t helpful: you’re never going to make a perfect film unless you’re an out-and-out genius, so it’s important to recognize when it’s time to jump in and sink or swim.

And this leads me to another advantage of making a film from a completed screenplay… While it’s certainly true that a lot of bad films have been made from good scripts, it’s also true that having the project properly written out gives you a better idea of where you’re going and helps you sense if you’re cooking up a turkey or a golden goose. All too often filmmakers have the former while thinking they have the latter. The sad truth of it is that not all films deserve to be made, and figuring this out at script stage can save a lot of people a lot of time and a lot of money. I suspect most filmmakers have an innate desire to create (because if they’re in this business for any other reason, they’re just plain stupid), but that doesn’t mean that every script they write is the one. There was a great story in the piece on knowing when to give up that John linked to previously, about a filmmaker who gave up on one script only to get his next one off the ground. For my own part, I’ve written scores of scripts that I know never deserve to see the light of day. The process of writing Life Just Is was a long one (five years, all told), but I was doing other things during that time, including learning my craft. There was a whole year where I didn’t so much as look at it. The fact that I still felt passionate about it after such a long absence told me it was the right film for me, but it could have easily gone another way.

Like a lot of independent projects, Life Just Is won’t be a film for everyone. I know that, and it’s a fact that was borne out by responses to the script. Some people hated it. But other people loved it. The general response was strong enough that I knew I had something. When the time came to put it into production, when I felt I was ready to make a feature and I wanted to pursue it properly, I set about trying to find a producer. Quite a few of the other articles in this series have spoken about using friends as your crew, but I’m not sure I agree with this. For one thing, putting your script out there and seeing who bites is a good way to test the water and find out if it has genuine appeal. But more importantly, finding people who believe in the project – rather than people who are there because they feel they owe you one – is one of the best ways to ensure passion and dedication. That’s not to say I didn’t work with friends on Life Just Is (some of the crew were people I’ve known and worked with for years), but primarily people came on board because they believed in the script and my vision for the project. I’m not sure I would have got the same support, or the same level of talent, without having a script. And this is equally, if not more, true of the cast: we did days and days of auditions because actors and agents responded so well to the script, meaning that we ended up with established talent in our cast, like Paul Nicholls (If Only, Bridget Jones: The Edge of Reason) and Jayne Wisener (Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street). In his recent contribution to this series, Alexander Poe says the same thing about getting Dexter actress Jennifer Carpenter on board his project: she liked the script.

On a side note, another point about choosing your crew, especially for a debut, is to go with people who will get something out of it for themselves. The chances are that if you’re microbudget you’re not paying, so don’t expect people with years of experience to jump on board for free. If people are taking a punt on you and your vision, return their faith. Several of the people in my crew had never made a feature before, and that’s what made it so exciting, challenging, and enjoyable to be on set every single day. Everyone was there because they genuinely wanted to be.

In concluding, it seems only right that I should address the issue of whether scripts add cost to the production by nature of calling for specific situations, locations and props. I would argue that there’s no real reason why, on a practical level, there should be any substantial difference in price between an improvised and a scripted piece – though, of course, that depends on what the script contains. But let me posit an idea here…

Anna Rebek wrote a very interesting contribution to this conversation, calling for microbudget filmmakers to abandon the idea of “embracing limitations” in favor of “staying true to the VISION.” But what if, as FollowMyFilm has rightly stated in the comments to Rebek’s piece, the project is conceived within these limitations? What if the limitations inform and help shape that very vision? Here’s something I wrote in my director’s statement:

When writing the script I knew that, as my debut feature, Life Just Is would have to be realised on a microbudget. As a result of this, I always kept in mind the practicalities of how it would ultimately be made. Although this created a number of limitations on what would be possible, it also helped me to focus on what was important to the story, and in this way I was able to turn these limitations into advantages. By freeing myself from the distractions which often come with larger-scale projects, I was able to concentrate first and foremost on creating an intimate character study, infused with the existential and spiritual dilemmas so central to, yet so ignored by, so much of modern life.

In his Letters to a Young Poet, the poet Rainer Maria Rilke suggests that when starting out it’s best to write from personal experience rather than trying to master popular genres, as it takes years to master your craft and therefore others have no doubt already tackled those same genres far better than you can. Elmer, in her embracing of “story,” seems to be making a similar point. So maybe there’s a middle ground here that offers a solution: microbudget films which embrace life, embrace limitation, but do it without compromise to artistic vision, and do it without abandoning all the other benefits that scripts can bring. As Christine has put it: it shouldn’t be about shrinking a story to fit a microbudget, but about finding a great microbudget story.

– Alex Barrett is an independent filmmaker, critic and festival programmer. To find out more about his work please visit www.alexbarrett.net or www.lifejustisfilm.com. You can also find him on Twitter @albaztks.

We are still running our sound mix contest here, plenty of time to get your film in and win a chance to have it mixed by a pro!

We’d never turn down the chance to hear from you, especially microbudget fans and filmmakers. To become part of the conversation please send us your thoughts, responses, and questions.