Back to selection

Back to selection

The Best Animated Films of 2011

It’s a good time to be making animated films, enough so that even regular indie filmmakers may want to sit up and take notice. Animation has always been on the cutting edge of film artistry and technology, and in a year that saw innovative use of motion capture, rotoscoping, CGI, and 3D (in documentaries, no less), an animated picture may be indie film’s next big thing.

2011 was also exciting because it gave us a wide open field for cartoons. For over a decade Pixar has dominated feature animation, but there’s now room for newcomers and underdogs to enjoy their place in the sun. Award nominations already reflect this: the five nominees for the Golden Globe’s Best Animated Feature Film prize are fairly straightforward, but the 18 films submitted for Academy Award consideration run the gamut in terms of style, audience, theme, and nationality. (More on that here and here.)

In the spirit of end-of-the-year wrap-ups, here are some of the best and most innovative animated features of 2011. Most of these were completed this year, but I’m including a few that are a couple years old but reached American shores in 2011. I’ll first look at native English-language films, then those from farther abroad.

America and England

The best animated film of the year — and arguably one of the best films of the year in any medium — is Gore Verbinski’s Rango. Besides the dusty and detailed visuals, the crackling dialogue, and John Logan’s intelligent script, Rango reinvents the western more than anything we’ve seen this side of Leone. Verbinski makes the transition into animation deftly and actually elicits a better performance from Johnny Depp than in any of the Pirates of the Caribbean films. Like Robin Williams in Aladdin, Rango could be Depp’s comic masterpiece.

2011 also saw its share of sequels and spin-offs. Another Alvin and the Chipmunks picture might not pique much interest with indie filmmakers, but The Smurfs emerged from a lengthy development hell with a picture that seeks to reinvent the franchise in a snarkier, hipper world than when Peyo first created the Schtroumpfs in 1958. Disney went the other way with its newest Winnie the Pooh film, under the guidance of animation veterans but fairly new directors Stephen J. Anderson and Don Hall. The new Pooh aims past Disney’s recent variants on the franchise — films named after Piglet, Tigger, and even the fictive Heffalump — to A. A. Milne’s original two books. The result still can’t completely please Pooh originalists like myself, but it has a warmth and intelligence that surprised some critics who expected Disney to keep cranking out quota quickies with this property as fast as its animators were able. The passage of time since the first Pooh film in 1977 is evident in things such as voice actor Sterling Holloway’s absence, but by and large the homes around the Hundred Acre Woods are untouched by modernity, making this a safe and welcome film for parents to take their children to.

2011 also saw its share of sequels and spin-offs. Another Alvin and the Chipmunks picture might not pique much interest with indie filmmakers, but The Smurfs emerged from a lengthy development hell with a picture that seeks to reinvent the franchise in a snarkier, hipper world than when Peyo first created the Schtroumpfs in 1958. Disney went the other way with its newest Winnie the Pooh film, under the guidance of animation veterans but fairly new directors Stephen J. Anderson and Don Hall. The new Pooh aims past Disney’s recent variants on the franchise — films named after Piglet, Tigger, and even the fictive Heffalump — to A. A. Milne’s original two books. The result still can’t completely please Pooh originalists like myself, but it has a warmth and intelligence that surprised some critics who expected Disney to keep cranking out quota quickies with this property as fast as its animators were able. The passage of time since the first Pooh film in 1977 is evident in things such as voice actor Sterling Holloway’s absence, but by and large the homes around the Hundred Acre Woods are untouched by modernity, making this a safe and welcome film for parents to take their children to.

DreamWorks also worked to keep two of its most successful franchises alive with Kung Fu Panda 2 and the Shrek “prequel” Puss in Boots. Neither film does much to mess with a previously successful formula, but the new Panda moves into darker territory, setting the property up for a third film and–following the Penguins of Madagascar — television series. Puss in Boots was likewise as expected: a satirical swashbuckler that gives a popular sidekick the spotlight, reuniting Antonio Banderas and Salma Hayek in a fun film that parents can enjoy watching alongside their kids.

Two original films worthy of mention are Twentieth Century Fox’s Rio and Aardman’s new CGI project Arthur Christmas. Rio, a fish-out-of-water tale about an exotic bird being rehabilitated in the tropics, is fresh and fun, and Arthur Christmas, which my daughter insists we see this Saturday for our New Year’s Eve filmgoing tradition, has gotten a lot better reviews than Aardman’s previous computer-generated film Flushed Away. With a Golden Globe nomination and strong box office, Aardman is showing they can please with CGI films as much as their traditional stop motion. And it’s nice to see a British Santa for a change.

Another Golden Globe nominee is already stirring up the expected controversy: is Steven Spielberg’s The Adventures of Tintin an animated film or not? Purists of course strongly believe it isn’t, but then what exactly is it? And when an entire film is created this way, is that any different than integrating one motion-captured character (usually Andy Serkis) into a live-action film? Weta Digital did much of the work for both Tintin and Rise of the Planet of the Apes, for instance, and to my eye it’s Spielberg’s film that is much more enjoyable to watch. All the technology aside, The Adventures of Tintin is a remarkable film, a strong adaptation of an iconic property that of course can’t please everybody but which remains remarkably true to Georges Remi’s original — again, largely through the decision to use animation rather than live-action.

One last English film that deserves mention is the underrated Gnomeo and Juliet, directed by Kelly Asbury from a script by a bevy of writers adapting the Bard for little tykes. This film also had a reportedly difficult development and release, but if my seven-year-old’s enthusiastic reaction is any indication it’s a great way to introduce Shakespeare to children — and a lot truer to the original than The Lion King’s Hamlet. We’ll see if the Academy agrees.

Foreign-Language Films

These films I admittedly haven’t yet been able to see, but I’m anxious to do so as they represent a much broader range of pictures than the American and British films, which are mostly CG and mostly geared towards children. For instance, Wrinkles (Arrugas), a Spanish film by director Ignacio Ferreras from a comic by Paco Roca, is set in a retirement home and centers around a character suffering the early symptoms of Alzheimer’s. It premiered in September at San Sebastian, so let’s hope it gets wide exposure and release in the English-speaking world.

These films I admittedly haven’t yet been able to see, but I’m anxious to do so as they represent a much broader range of pictures than the American and British films, which are mostly CG and mostly geared towards children. For instance, Wrinkles (Arrugas), a Spanish film by director Ignacio Ferreras from a comic by Paco Roca, is set in a retirement home and centers around a character suffering the early symptoms of Alzheimer’s. It premiered in September at San Sebastian, so let’s hope it gets wide exposure and release in the English-speaking world.

A second Spanish film, Chico & Rita, premiered at Telluride in 2010, but has just begun its Oscar-qualifying run in Los Angeles this month; expect a general release by GKIDS early next year. This film, co-directed by Fernando Trueba and Javier Mariscal, is a bolero love story set in pre-revolution Cuba. It’s received rave reviews, including praise for its music and brash yet lush visuals.

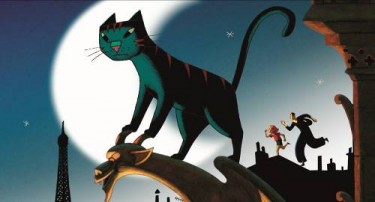

Moving east to France, 2011 saw the release of Joann Sfar and Antoine Delesvaux’s The Rabbi’s Cat (from Sfar’s comics), Jean-Christophe Roger’s 2010 The Storytelling Show (which had its US premiere at the New York International Children’s Film Festival this year), Jacques-Remy Girerd’s 2008 Mia and the Migoo (with an English-language version, including Matthew Modine, James Woods, Whoopi Goldberg, and Pixar veteran Wallace Shawn, released this March), and directors Jean-Loup Felicioli’s and Alain Gagnol’s A Cat in Paris (2010, but which won the Children’s Jury Prize at the Chicago International Children’s Film Festival this October).

Moving east to France, 2011 saw the release of Joann Sfar and Antoine Delesvaux’s The Rabbi’s Cat (from Sfar’s comics), Jean-Christophe Roger’s 2010 The Storytelling Show (which had its US premiere at the New York International Children’s Film Festival this year), Jacques-Remy Girerd’s 2008 Mia and the Migoo (with an English-language version, including Matthew Modine, James Woods, Whoopi Goldberg, and Pixar veteran Wallace Shawn, released this March), and directors Jean-Loup Felicioli’s and Alain Gagnol’s A Cat in Paris (2010, but which won the Children’s Jury Prize at the Chicago International Children’s Film Festival this October).

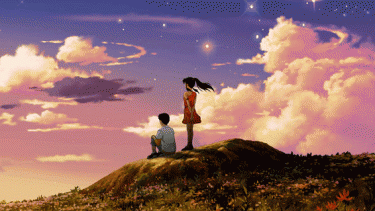

One Asian film that caught my attention is The Dreams of Jinsha. This 2010 film, written by Xiaohong Su and directed by Daming Chen, is the first major Chinese animation in many years. In 2D, it bears the mark of Japanese anime, particularly historical films like Princess Mononoke, and hence looks to me a lot like a cultural hybrid akin to Tsui Hark’s animated version of his Chinese Ghost Story films. The story deals with a modern teenager thrust back to a magical medieval land, and though it didn’t get an Oscar in 2011 it was seen here in the US this year.

One Asian film that caught my attention is The Dreams of Jinsha. This 2010 film, written by Xiaohong Su and directed by Daming Chen, is the first major Chinese animation in many years. In 2D, it bears the mark of Japanese anime, particularly historical films like Princess Mononoke, and hence looks to me a lot like a cultural hybrid akin to Tsui Hark’s animated version of his Chinese Ghost Story films. The story deals with a modern teenager thrust back to a magical medieval land, and though it didn’t get an Oscar in 2011 it was seen here in the US this year.

Finally, from the Czech Republic comes the perhaps the most intriguing animated film all year: Tomas Lunak’s Alois Nebel, also an adaptation of a graphic novel by Jaroslav Rudis and Jaromir 99. This decidedly adult and apparently black-and-white rotoscoped film evokes Waltz with Bashir, A Scanner Darkly, and the noirish feel of Ashes and Diamonds. Noir, in fact, is the primary way to describe a murder mystery set on a train at night, with a suspicious mute stranger and a wrong man suddenly thrust into the melee. A cross between Hitchcock and Wajda, but with a possibly transcendent ending, this film looks a far cry from Rango and Winnie the Pooh, as the trailer attests: