Back to selection

Back to selection

THE 2012 HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH FILM FESTIVAL

The strength of the Human Rights Watch Film Festival is also its weakness. This year’s 23rd edition boasts 16 doc and fiction flicks from 12 countries – yet most fall firmly in the category of solid ITVS fare (in fact, only three are narrative features). Like with the agribusiness detailed in Micha X. Peled’s Bitter Seeds, about the epidemic of farmer suicides in India, variety is often an illusion – especially when U.S. or U.S. co-productions are in the majority. This is another way of saying that, yes, the chances of seeing a stinker at HRWFF are slim, but there’s also not much in the way of stay-with-you cinematic experience on display, magical discoveries worth dragging yourself up to the Film Society of Lincoln Center Walter Reade Theater for, rather than just wait until the likely PBS broadcast and see it for free. Fortunately, after viewing more than half of this year’s selections I did manage to find the exceptions to what might be called the “Ken Burns Rule.”

Two films in particular renewed my faith in the power of the moving image. The first was Kirby Dick’s The Invisible War, which garnered the Audience Award for U.S. Documentary at Sundance and the Nestor Almendros Award for Courage in Filmmaking at HRWFF – and might just be one to watch for next year’s Oscars shortlist. The veteran doc-maker – who I had the pleasure of meeting at last year’s Santa Fe Independent Film Festival, where he showed work-in-progress clips from the film – has long struck me as an interestingly paradoxical director. He’s more hard-working craftsman than artist, and fearlessly tackles taboo subjects from BDSM to the MPAA, through a fairly mainstream filmmaking style. Dick’s latest takes on the issue of rape in the military, opening with rarely seen archival footage from the earliest days of women in the armed forces, from recruitment ads to shots of basic training. Interviews with lady soldiers, who offer passionate testimony about their love of the military and the reasons behind choosing to serve their country, soon follow. But the patriotic spirit quickly fades to black when words on the screen reveal that over 20% of female vets have been sexually assaulted. Indeed, it’s the title cards with their enraging statistics, as much as the former soldiers reliving their ordeals (often violent rapes) through painful accounts, that turn The Invisible War into a loaded gun. 15% of enlistees have attempted or committed rape before entering the military (twice that of the normal population). Women who’ve been raped in the armed forces have a PTSD rate twice as high as men who’ve been in combat. An estimated 1% of males in the military – that’s 20,000 soldiers – have been sexually assaulted in the past year as well. WTF?

In addition, The Invisible War makes a compelling case to counter my recent complaint that most “activist” doc-making is as likely to change the world as your average Hollywood popcorn flick. Why should we as moviegoing civilians care enough to join the fight for the reform of military policy when there are so many other more important issues (i.e., the economy) to worry about? Serial rapists in the armed forces don’t touch our world – until, of course, they inevitably do. For upon being discharged, the majority of these predators, without so much as a slap on the wrist, are free to roam and prey in civilian clothes, never to be flagged on any “watch list.” Food for thought. And if you ever, like me, gave up hope that cinema could make a dent in an armored and flawed system impervious to even the biggest lawsuits, be sure to stay for the film’s final, and truly remarkable, end titles.

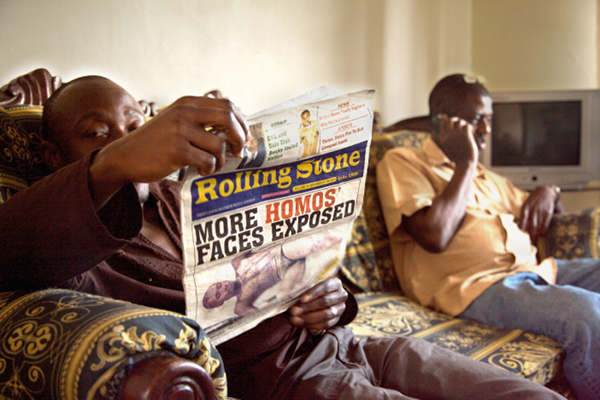

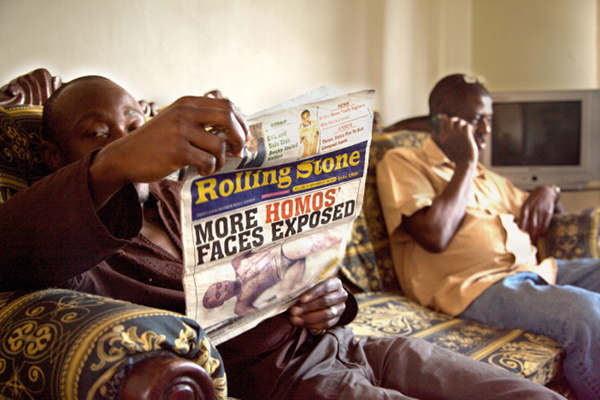

But the one doc to really rock my world was the film that recently swept the Berlinale and just nabbed Best International Feature at Hot Docs. Call Me Kuchu is Katherine Fairfax Wright and Malika Zouhali-Worrall’s gripping account of unbelievably bold LGBTI activists in Uganda, who make the ACT UP crowd seem like sissies (and whose organization, Sexual Minorities Uganda, has an equally catchy acronym – SMUG). With intimate access the filmmakers focus on four of its members, two gay men and two lesbians (who are also part of the Coalition of African Lesbians), led by the small-statured yet charismatic, tactical and fearless, “advocacy and litigation officer” David Kato – a Martin Luther King, Jr. figure, both heroically and tragically, if ever there was one. In a country where homosexuality is outlawed, and where the major tabloid Rolling Stone incites hate crimes (and, not incidentally, sells papers) by publishing the names and photos of kuchus (Ugandan slang for queers), it’s shocking a guy like David Kato – the first gay man to come out of the closet in Uganda – would even exist. Not content to simply allow us to get to know the flesh-and-blood individuals affected by Uganda’s endemic homophobia as they struggle for basic human rights (including, as The Clash would have it, “the right not to be killed”), the co-directors expand their focus to provide an all-inclusive and crucial context.

To this end, we’re introduced to an array of anti-homosexual, politically powerful talking heads – including Giles Muhame, the unapologetic and horrifyingly glib managing editor of Rolling Stone. (Muhame is also Uganda’s black answer to George C. Wallace – basically making the same case against homosexual-accepting international influence that the governor of Alabama did to counter black integration being federally forced upon the South.) We meet a bishop who faces the wrath of the Catholic Church for wanting to build a safe house for the LGBTI community – and for just doing his job by offering counseling – as well as hear from pundits who explain that Uganda’s (pro-death penalty for HIV-positive men) Anti-Homosexuality Bill was backed by the Life Network, an American evangelical group. (Ironically, the criminalizing of homosexuality was actually introduced by the West.) The doc moves briskly, taking us on an in-depth journey filled with paradox and hypocrisy, with uplifting moments and eye-opening surprises. Until, of course, we reach that final heart-wrenching half hour. For we know from history that the price of change through nonviolent action is forever higher than anyone wants to believe.