Back to selection

Back to selection

This Is Where You Work

On the Surprisingly Influential Nature of Offices by Zachary Wigon

This is Where You Work: Eve Sussman

What sparks creativity? It’s safe to assume that an artist’s work environs affect the process of art-making, so perhaps it’s possible by examining those environs to find some of the seedlings of ideas, of productivity, that space engenders to get the mind to engage with work. That was the idea behind the “This Is Where You Work” series, and when I turned my focus to my first subject, filmmaker Braden King, I was a bit shocked by how relevant the idea was – the items and artifacts filling King’s workspace created a sort of map of his personal life and history of art-making, much in the way that the characters in his recent film Here use different kinds of cartography to chart personal histories.

This was in mind when I went to check out subject number two, artist and filmmaker Eve Sussman. Sussman’s most recent film, whiteonwhite: algorithmicnoir, was at Sundance 2012 (and was covered by this website during the festival). whiteonwhite stands alone in terms of its conceptually innovative structure — it’s a film that auto-edits. The film edits itself according to an algorithm, which means that each time it is being watched, it plays in a different order.

Bearing that in mind, it was less surprising when this time I found, again, that the filmmaker’s office space mimicked the themes of her work. Like whiteonwhite, Sussman’s workspace is modular – she explained that she doesn’t have a set desk, but rather, works from various places at various times – and many-functioned. With a lot of room, the South Williamsburg loft, where she’s lived and worked since 1998, functions not only as an office, but a theater, studio, and social space. The space, peppered with artwork and notes and other various mementos, has the feel of an incredibly vast closet of all the stuff that’s too weird for your friends and relatives, and invariably gets tossed out of sight.

However, the arrangement of the artworks in the space isn’t totally haphazard – there’s a sensation of some kind of sublime, transcendent order arising out of the chaotic scramble on the walls, the various works and images that fight for your attention. It’s the sense of realizing that a studio covered with artwork is often greater than the sum of its parts, that a collection of art stimulates the brain in ways that the individual works cannot, on their own. When you look at a space and are confronted every day with various items, all aesthetically unique and distinct, you learn to refocus your attention on different things constantly – much as an algorithmically-edited film restructures the order of its scenes. What interests Sussman, I imagine, is not one structure versus another, but rather, the way that any structure can seem as valid as any other – an egalitarianism of structure. Having artworks and other aesthetic items constantly competing for your visual attention, of course, is a good way to become acclimated to the legitimacy of different ways of seeing.

In keeping with the large, complex nature of the studio space, I had a long, rambling conversation with Sussman that touched on any number of items and themes. These are some of the things we discussed.

Eve Sussman: The neighborhood has changed dramatically. There wasn’t a 27-story luxury tower across the street when I moved in here! The Hasidic community has grown, and the luxury community has grown. Luckily, the Hasidic community keeps the luxury community out of the south side. The Hasidic developers own a lot of property, and they rent primarily to Hasids. There are some mixed buildings too, the projects are mixed, mostly Latino and Hasidic. In the ’70s, the artists started coming, by the ’90s people started being displaced by rich developers and yuppies that could afford the exorbitant rents. The community has been devastated – the rezoning of the waterfront was the kiss of death for the artistic community. We were absolutely screwed by this mayor and the previous one. Bloomberg hasn’t met a developer he doesn’t like. As soon as you rezone neighborhoods for residential, you push out creative, entrepreneurial culture, because artists often live and work in manufacturing zones. You have to keep in mind that residential rezoning isn’t about creating houses for average people, it’s about housing the rich, the 1%. Small business gets priced out to make way for luxury housing. It’s bad for the arts, it’s bad for jobs and it’s bad for the working classes.

When my partners and I came here, this was an empty floor. No windows, no plumbing, no walls. Pigeons and rats. The owners had owned the building for about 15 years. They had 1970s’ CB radios on the top of the building. They had a company that stored lampshades on the seventh floor. The rest of it was empty. We had to build everything.

Sussman: Simon Lee and I run the Wallabout Oyster Theatre. We move the theater from his space to my space depending on what we’re doing. An artist named Jan Baracz did an installation with these beautiful seats – the leather ones – and the risers, and when the installation was over he didn’t have a place for them, and he offered them to us for what he spent to get them. As soon as we had them, we realized, wait, once you have seats and risers, you have a theater! Simon and I both work with actors, and we thought, we could do stuff with some of the actors we know. So far, we’ve given the theater to the actors we know as a platform for them to do work they’re interested in. Jeff Wood and Nesbitt Blaisdell have done things here a couple times. Neither Simon nor I have directed anything here yet, but we will, in the future. So far we’ve been the producers.

Filmmaker: Was working in live theater a conscious interest before you came to have a theater in the space?

Sussman: It is an interest and some of the films have been like large live theatre events documented on film –– specifically the fight scene at the Herodion Theatre in The Rape of the Sabine Women. I’ve also collaborated with dancers and I’ve worked as a video artist with live performers. But I never thought we’d be doing it in our studios the way we are with Wallabout. All of that came about very organically.

Filmmaker: Having a theater set in your workspace, do you ever feel like the set works its way into your thought process somehow?

Sussman: For sure it does. Both the theater itself and sets we create for it. The set we built for Hughie, the Eugene O’Neill play, was really beautiful. For a while I thought, I don’t want to take it apart, I can use it for something else. It was supposed to be a hotel lobby, but it could easily be a speakeasy. It had a 1930s ambiance. It changed the feel of the whole space. Building sets is something I’ve done a lot. We built Yuri Gagarin’s office for whiteonwhite. When we took apart the Hughie set, I thought, I can put it back together really easily. It’s like, when you asked me where my desk was, and I said “My desk is always moving” – I’m always transforming the space. Everything’s on wheels, everything can be moved around. Even the studio wall. The desks can fold out or in –– it can be flat or it can be furniture and the entire wall is magnetic – sheathed in sheet metal. I also think of that wall as a potential film/theatre set. Since everything can be architecturally transformed – the entire space is a set design.

Filmmaker: Seeing as how whiteonwhite is about a narrative that constantly rearranges itself, and your workspace is an environment that you’re constantly rearranging physically – well, I wonder if you think that’s coincidental.

Sussman: No! It’s something I think about a lot. I like the fact that you can always change the context, you can change your understanding of what’s going on, that everything’s modular. I have a real interest in modular architecture, temporary architecture and uses of pre-fab. It’s funny, because one of the things Simon and I have been talking about is trying to buy a lot that we would build a set on and shoot something on, and then sell the lot to pay for the production. To me, that’s a great idea because you can take the NYC real estate game and actually use it in a creative way – get it to fund your next project. I’d have to find a lot I could afford, of course, which might be a tall order, but maybe not impossible – I’ve been perusing the NYC auction site a lot. I’m also interested in the itinerant lifestyle. whiteonwhite was an itinerant film – shot in these different landscapes, different places, leading to different understandings of what’s going on around you.

Filmmaker: It’s about shifting perspective, right? Even if you shift perspective just a bit, you’re going to have a different interpretation of what is happening right in front of you. Like what happens when you rearrange your workspace – you gain a new perspective on how to see things.

Sussman: Yeah. I just treat it as this really organic thing, where you don’t know what’s going to happen from one moment to the next.

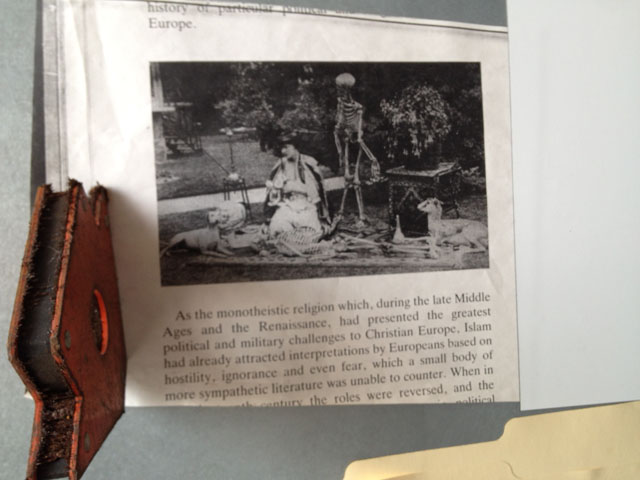

Sussman: It’s a picture I found in an old research folder, xeroxed from a book I was using years ago – Images of Women: The Portrayal of Women in Photography of the Middle East, 1860-1950. The image is bizarre. It references baroque painting in the way that it’s set up and has a weird theatricality. I’m interested in how the West views Islam and am really aware of the rise of Islamophobia in America, which is so ignorant and upsetting. I’m very curious about how the “other” is pictured. During the Cold War the “other” was anything Soviet. At the end of the Cold War “the other” morphed into something much harder to pin down – a shape-shifting amorphous other that is much more frightening. The core of all horror movies. I went to high school in Turkey and when I was a kid my mother drove the Khyber Pass. I’ve never understood the Islamophobia and the overall xenophobia that’s so prevalent now in America, which has always been here, lurking. Even as a high school student in Istanbul, I was aware that the next “other” would be Islam. Here’s what that book says about the photo: “Little is known about this photograph, but it is assumed to have been a private joke.” That’s total conjecture. “It is unlikely that the objects in the photo had any particular meaning for the participants other than to increase the exotic quality of the photograph.” But the author doesn’t actually have any idea.

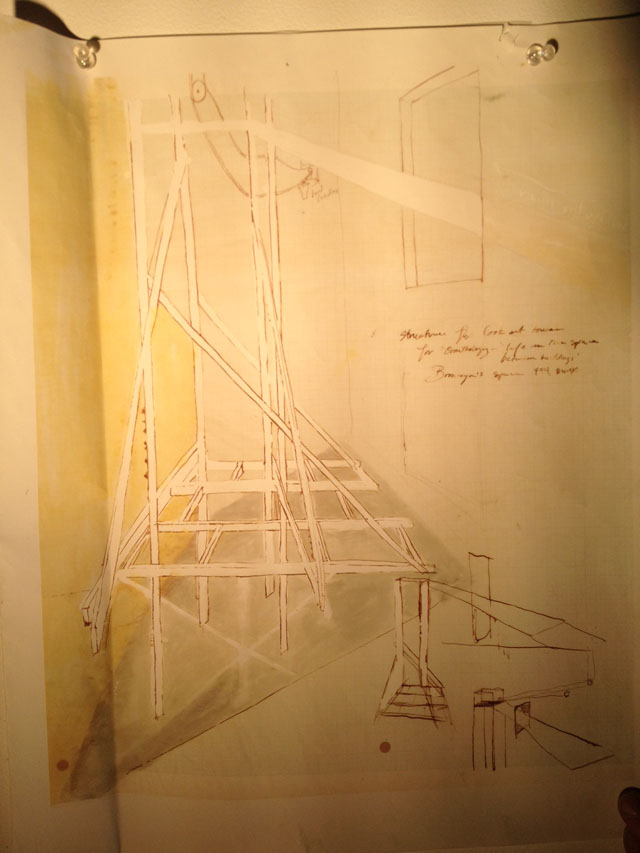

Sussman: This was a drawing for a piece called Ornithology, which was my first solo show in New York, in 1997. I made installations then. The piece was a surveillance piece of pigeons in a light well in a fourth-floor gallery. There were 12 surveillance cameras. We built a tower and a ramp and a platform, so the audience could be on the platform between the buildings and observe what was going on in the light shaft, which was filled with pigeons. I put bird feed out there. I did pieces at that time that involved live surveillance and some kind of structure or architectural change. I was creating site-specific things that had an architectural element.

Filmmaker: It’s interesting, the way you have these traces of all these works you’ve done in the past, these spectral traces of old works lying around and on the walls. It’s like they coexist here and maybe create some sort of ghostly aura representing everything you’ve done up until now. I wonder if these traces influence you in some way?

Sussman: I’ve been thinking a lot about how things are kind of circular, and you go back to the ideas you had 10 or 20 years ago. I’m definitely interested in some of the stuff I left behind 15 years ago or so. I think that’s probably why there are things pinned to the walls from the 90s. I think I went off on a tangent that had to do with making things that looked more like movies. I used to do things that were more installation based – I still used film and video, and photography, but they were more site-specific, more difficult to classify. There’s a site-specificity and an architectural aspect that I’m interested in with that older work. The work was responsive to its surroundings. I’m trying to get back to that, to remember that there’s a whole type of work that I used to make that I haven’t made in more than ten years. And to remind myself that I don’t have to do big projects that are kind of like feature films that can take years to complete. I don’t work in the film world, I work in the art world. I assume most people you talk to for Filmmaker, when they’re not making a movie, they’re off directing a commercial or teaching. I don’t teach and I don’t direct commercials. I’m not a director for hire, so doing big productions like Rape of the Sabine Women or whiteonwhite means not working through ideas quickly – a lot of things get back-burnered. I miss that mode of working that was more spontaneous. The way most films are made is not at all spontaneous. The process kind of kills creativity. I’m much more interested in, how I can work with motion pictures – in a live setting – and have it respond to the world around me.

Sussman: This is a postcard from Brasilia. It was sent by Angela Christleib, who was one of the cinematographers for whiteonwhite and like Rape of the Sabine Women. We’re both very taken with high modernism and the utopian ideas that modernist architecture was borne of.

Filmmaker: And this natural form right next to it – the swan.

Sussman: Yeah. Next to that architecture. It certainly makes me want to go to Brasilia!

Filmmaker: And travel back in time.

Sussman: Well it’s funny, when we shot in Aktau, there was that same idea of being in the future and in the past at the same time, which is what you love about that architecture — it feels like it must be sci-fi, but you’re going back in time. That simultaneous going forward and going back is really interesting.

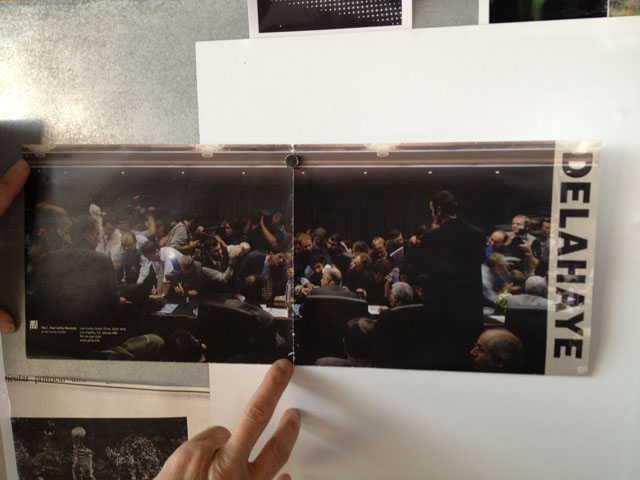

Sussman: We shot big crowd scenes in Rape of the Sabine Women – we had hundreds of extras – and when I came across his work at the Getty I thought, Oh my God, I really want to meet this guy. You know what it is?

Filmmaker: Trading floor?

Sussman: It’s even weirder than that. It’s an OPEC meeting. “The 132nd meeting of the conference in its Vienna headquarters.” I actually know that he created this from a few different photos. I went to his studio in Paris and spoke with him. He’s awesome. Out of the blue I called him up and said, “I want to come meet you.” They’re huge – they’re about twelve feet on the wall. He’s a very intense guy – an ex-Magnum photographer.

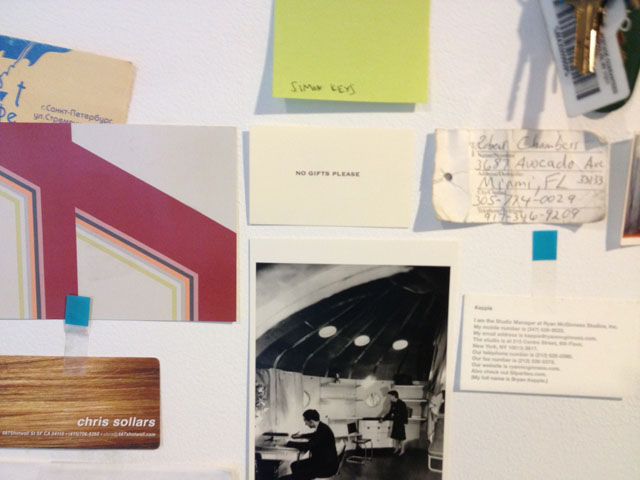

Filmmaker: I really like “No Gifts, Please.”

Sussman: I think that was just from someone’s wedding invitation.

Filmmaker: But it made it onto your wall for a reason.

Sussman: There was just something about the understatedness of it. Something very sweet about it, I thought.

Filmmaker: To me there’s something sort of sci-fi and otherworldly about it.

Sussman: About the “No Gifts, Please”? Really? Why so? I like that idea, but I’m not quite sure I get that out of it. Like in the future, there will be no gifts?

Filmmaker: There’s so much negative space, and then in the middle you’ve just got these three little worlds. There’s something cold and strange about it.

Sussman: To me it’s just horribly good taste. Scarily good taste. Which is sci-fi. You could say that in the future there will be terrifyingly good taste.

Filmmaker: The font is cold though.

Sussman: The font is cold — you have a point. There’s something a little sinister about it. I hear it in my head‚ “No gifts, please. If you give us a gift —— fuck you! You do not know what will happen to you!” It’s almost a threat! Like, God forbid you should give us a gift.