Back to selection

Back to selection

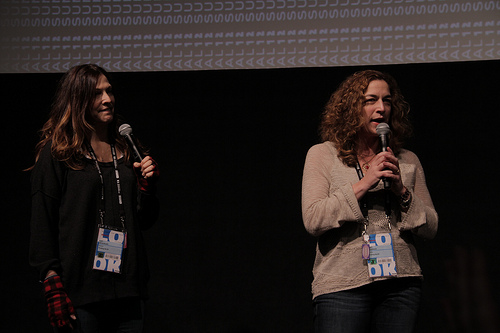

Directors Lori Silverbush and Kristi Jacobson on A Place at the Table

A Place at the Table

A Place at the Table If Food, Inc. freaked you out, prepare to be galvanized by A Place at the Table, another hot-button food doc being released by Participant Media and Magnolia Pictures. The film, which boasts the involvement of celebrity advocates Jeff Bridges and chef Tom Colicchio, fixes its curious eye on America’s hunger crisis, whose staggering stats add up to the distressing fact that 50 million folks in this country, many of them kids, don’t know when or how they’re getting their next meal. It’s a monster of a topic, with arms that stretch to the realms of politics, medicine, and agriculture, and the directors who stepped up to dissect it are Lori Silverbush and Kristi Jacobson, a narrative filmmaker and a documentarian, respectively. Combining their powers, the duo aim their spotlight at those suffering from food insecurity, along with a who’s-who of talking heads and, finally, our government, which the movie insists need only use the power it already has to fix these matters. In SoHo, at the Crosby Street Hotel, Silverbush and Jacobson both sat down to discuss the many problems A Place at the Table unearths, revealing a mutual passion — and, yes, hunger — for solutions in the process.

Filmmaker: There’s a wide array of human characters in this film who represent the crisis. There’s young Rosie in Colorado, single mother Barbie in Philadelphia, etc. Can you describe how you found your subjects?

Silverbush: Sure! One of the things we were most surprised to learn is that there’s hunger in every single county in the United States. The first step is really to reach out to people who are working on the front lines of the issue and trying to make it better. Every single community has had a huge sort of citizen response, whether it’s through church groups, charity groups, community groups, or faith-based groups. You’re seeing that people are jumping in to try to meet the needs of their neighbors, so we reached out in many states and typically somebody would say, “We know of a family,” or, “We know of somebody who’s working to try to de-stigmatize this issue in their community.” There was no shortage of stories and we usually had somebody trusted in the community bring us in and try to introduce us. Then we spent time establishing that trust and getting to know people and hoping that they would share what is, sadly, very humiliating for them and shameful. The shame really shouldn’t be there, but that seems to be the way people felt.

Jacobson: And it was kind of a process over time of sort of one story taking hold. For example we read an article about the Witnesses to Hunger photo exhibit, and met Dr. Marianna Chilton and starting meeting those women of the Witnesses to Hunger — those 40 women who were getting together to share their stories and raise their voice. And we were just completely drawn to Barbie and understood immediately how compelling she is as a subject and as a person. And that sort of then informed the idea that, as Lori said, if there’s hunger in every community, and in particular in places where you don’t expect it, you know, we sought to see what was going on. And we wound up in Colorado, where we just followed the guidance and advice of people who were on the ground. But then, once we landed, met [film subjects like] Pastor Bob and Leslie Nichols, we started to really understand how pervasive the problem is in that community, we sort of know this was a place where we wanted to explore this problem further. And, of course, we were fortunate that they welcomed us, after some time. So, it was a process.

Filmmaker: What many viewers are likely to find surprising — I certainly did — is that food insecurity and obesity often go hand in hand, because nutritious food is so scarce for those who are struggling. Did this surprise you as well?

Silverbush: Yeah, definitely. We had an inkling about it, but then we started to see that millions and millions of people in this country are existing on a third-world diet. They are perhaps not experiencing the hunger pains or the starvation conditions that we normally associate with hunger, but they’re essentially being asked to lead a productive life without the nutritional support to do that. For many people, the food that’s most affordable is processed crap. That’s what’s in their budget, that’s what they’re able to bring home so they aren’t having that crippling feeling of hunger. But as a consequence of that diet, they’re dealing of obesity and myriad preventative health problems as a result. We’re seeing kids now who not only are candidates for preventable type II diabetes, but struggling with pre-heart disease. Signs of pre-heart disease! That’s something we normally associate with people who are either smoking or are much much older. So, yeah, we were surprised to learn about the connection and to learn what was causing it.

Jacobson: Yeah, and I think when we set out to explore the issue of hunger in America, I don’t think we had any idea how many different ways hunger affects individuals. And, certainly, discovering that really important link between hunger and obesity — it was something we knew, once we understood it, would be a revelation to audiences. And that’s why we went to Mississippi: here is the state that ranks highest for food insecurity and obesity. It gave us the opportunity to explore the connection between the two.

Silverbush: And it gave us the opportunity to demystify, or debunk, some of the mythology, because, right now, obesity is so often talked about as being the result of a bad lifestyle, or poor choices, and we were determined. We’d seen how the media sort of participated in making people feel like they’re somehow to blame for just super-sizing and making really bad choices. Perhaps that is, in some ways, the case, but that wasn’t what we were finding. The science and data are showing that, more often not, it’s a function of what people can afford, and not just bad choices.

Filmmaker: You have some celebrity friends helping the cause here, like Tom Colicchio and Jeff Bridges, both of whom have been doing their own individual parts to fight hunger. How did their collaborations with you happen?

Silverbush: Jeff Bridges reached out to Participant Media, our producing partner, to ask how he could get involved! This was an issue he’d been focusing on for 30 years, and he learned we were making a film from his friend, T-Bone Burnett, who was scoring the film. The great thing was that he was not a celebrity lending his famous face to an issue — he was an actual authority on the subject. That was refreshing, and very, very useful. Tom Colicchio brought the unique perspective of someone who, in his capacity as a chef/restaurateur/TV personality, had helped raise millions of dollars over the years for hunger charities. He felt real frustration that the problem of hunger in the U.S. just keeps getting worse, even as chefs were raising more money than at any point in history. He was frustrated that no one seemed to be questioning the situation.

Filmmaker: The film points out that this issue has been brewing, particularly, since 1980, when the costs of fruits and vegetables began to rise considerably, and when the obesity epidemic broke out in America. Had you been following these developments? Which is to say, has this film been a long time coming?

Silverbush: Hmm. I think the film was a long time coming, but maybe not because I’ve been watching the developments. I think the way that things have been moving and progressing in this country as a whole has informed, at least for me, the decision to work on this. I am personally really frustrated at the culture of blame that ends up substituting for meaningful discourse on these issues. Some years ago I directed a narrative film called On the Outs, and I worked with a group of kids to research it. It was scripted, but it was based on the lives of real kids who were locked up in juvenile jails, and I wanted to know what was going on for them. And I remember once I asked a kid who was locked up — and she was smart and really terrific in a lot of ways — and I said to her, “God, it must be really hard to be locked up like this when you could be out in the world enjoying everything it has to offer.” And she said, “Honestly, here, I get fed three times a day.” And I was so rocked by that, and I started to make a connection for myself, where I thought, “What kind of society are we living in where kids will seek out a jail situation so they can get fed?

Jacobson: I think for me, I would agree with Lori that, rather than a specific issue like food or food prices, it was more about this culture of blame and this increase in inequality that has become a bigger and bigger problem in our country over that same period of time. And I think I was drawn to tell this story because of the really deeply, personal human aspect of it, and the fact that there is an injustice happening in this country right now around this issue. I believe in the power of film to not just awaken people to the existence of this problem, and to make what is an invisible problem visible to all, but to engage those same people in being part of the solution. It’s been a long time coming in terms of those deeper, underlying causes that are troubling to me as a person and filmmaker.

Filmmaker: The whole food stamp issue is a controversial one, simply in regard to who “deserves” government aid. Your film is rather clear on what is, what could be done, and what should be done, but what about this issue in particular did you find most revelatory amid your process?

Silverbush: That some people in our government feel that kids don’t “deserve” to eat every day.

Filmmaker: And the people struggling most with this issue seem to be those who are on government aid or are in these so-called “food deserts.” Or both. Do either of you know anyone personally who are in these situations, outside of those who you met on production?

Silverbush: First, to speak to what you just said, I think, quite frankly, that the numbers are greater than just the people who are on government assistance. At this point we’re looking at close to 50 million people, and 80 percent of those families who are getting government assistance have a working adult in the household. So, it’s a much broader portrait than what most people assume. Do we know anyone personally? Yeah, I personally met a little girl — I was mentoring her and I thought I was helping her by helping her get out of public school, where she was floundering, and into a private school that helped kids with learning disabilities. And I got a call one day from the principal of that school, who said that she was foraging in the trash for food. And she wasn’t able to focus, she wasn’t able to participate in school, and she had behavioral problems — things we would normally blame her for. And it wasn’t a public school, so they didn’t have the free meal that is, for many of these kids, their only meal of the day. It was devastating. It definitely inspired me to find out more. That’s one example. And I’ve met many, many people in the same situation.

Jacobson: I would say that I am fortunate in that, in my own childhood, and my own life, I’m not wanting for food and not experiencing hunger and food insecurity in the ways that so many people are. But, certainly, I have many friends and people I know who have been in the situation as a kid, or are currently in the situation. It’s all around us.

Filmmaker: There a lot of arms to this issue. The agricultural end, the food stamps end, the medical element, the multiple movements like “40 Women, 40 Cameras.” Did you ever feel overwhelmed, like there was too much material for one film?

Jacobson: Ha! Every day! Did we ever not feel overwhelmed?! Yeah, I think from the minute we understood how pervasive the problem is, and second of all, how complex it is, we felt overwhelmed. But we were fortunate enough to work with a group of really talented producers and editors. We worked through a lot of that in the edit room, in terms of finding the balance — we hope we found the right balance — of the subjects and the characters who we spent so much time with, capturing their stories. We wanted that to be the driving force of the film. But, at the same time, it’s a complicated issue and we needed to figure out ways to parse it out so that people would understand not just that there are hungry people in America, but why. So it was certainly a many-tentacled beast that we managed to tame, again, through the great talent and skill of three editors that we worked with simultaneously to find that balance.

Silverbush: You should have seen in our offices — we still have huge rolls of paper lining the walls with various structural scenarios. Because it was a big, hairy beast. We could have made an entire movie about how we got here. We could have made a whole movie about the health consequences and medical consequences and science of it. The fact that we wanted to cover all of this and yet give the most real estate to the people and the stories that we encountered—and let them tell their own stories, because that’s riveting viewing—was a challenge every day. You should come by our office and see it. I still have it hanging everywhere!

Jacobson: And at the end of the day we are certainly proud of the finished product, and the balance that we hopefully struck. At the same time, there are many nights we — or I — would wake up like, “I can’t believe we couldn’t get that story in!” So many really important stories that ultimately could not make it into the film, but are nonetheless important.

Silverbush: And for the record, we can just let you know some of them here. For example, we were not able to cover senior hunger, which is a massive problem in this country. We were not able to cover Native American hunger, or the problem in immigrant communities. There are many, many areas, like military families. One of the largest groups of people collecting food assistance in this country are military families, often with parents actively engaged in fighting overseas. These are huge stories that could have occupied their own films, so obviously we couldn’t tell all of them. And we do have our regrets, but overall we think we were able to give people a very comprehensive look at something that is in our power to fix and solve.

Jacobson: And, from the start, when we partnered, since Lori’s background is in narrative film and mine is in documentary, our hope was to present this in a way that was cinematic, and that was driven by story and character, and we tried to. But at the same time there’s a hell of a lot of information. I think one way that we worked it out was getting to work with people like T-Bone Burnett, and having the money to shoot aerials. This broadened our toolbox in terms of hopefully contributing to that cinematic experience.

Filmmaker: The common goals among those depicted in your movie seems to be the reform of agricultural policies and an ultimate end to hunger by 2015. Having been in the trenches now and seen what you’ve seen, do you think those goals are realistic?

Silverbush: One hundred percent. It may not be easy, but nothing worth fighting for is. It will require that Americans shed some cynicism about our democracy and demand from our elected officials that they fix the problem. We need to hold our representative’s feet to the fire if they don’t, and be willing to call them out as “pro-hunger” if they’re advocating for policies that make hunger worse. An informed and passionate electorate is unstoppable.