Back to selection

Back to selection

True/False Dispatch #2: Sleepless Nights and Computer Chess

Sleepless Nights

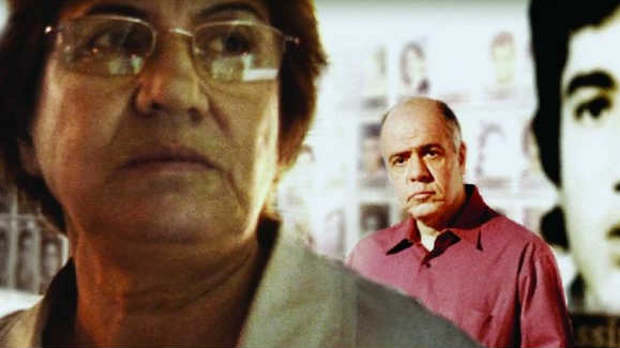

Sleepless Nights Making its North American premiere at True/False, Eliane Raheb’s Sleepless Nights is ostensibly about the Lebanese Civil War’s fallout. The opening title cards recap the conflict’s history in a bewilderingly quick synopsis, and if you’re not already informed on the subject (I went in shamefully ignorant), it’ll take a while to get your bearings. The principal subjects are Assaad Shaftari, a former Christian militia senior intelligence official, credited with approving some 500 deaths; and Maryam Saiidi, whose son vanished following one skirmish — the “battle of the science building” — out of a long, complicated history (the War lasted 15 years in some form or other). The event’s macro significance among many face-offs is never contextualized.

During early interviews, Shaftari and Saiidi’s responses are fragmented from a variety of angles, visualizing in a literal way history’s multiple points-of-view and impossible-to-reconcile perspectives. Raheb is an active presence, grilling people on camera or setting up confrontational meetings between parties who despise each other or can’t get along. Scenes aren’t so much staged as instigated, either by Raheb or Saiidi. The former is necessarily persistent and unrelenting with Shaftari, who sometimes lies to her face, flatly denying statements previously made on the record. At another point, he gets Clinton-ishly disingenuous with his vocabulary, rejecting the term “mass murder” with legalistic quibbling, at which point Raheb cuts to a boy covering his gaping mouth mid-scoff, the average citizen calling bullshit, a form of editorial comment through social context rather than direct cause-and-effect.

Raheb’s broad goal is to help Saiidi find her son, or more probably his body; scenes of Shaftari musing on remorse or participating in peace activism activities alternate with Shaiidi-related procedural interludes. During some interviews, the camera drifts left to right from panoramic, skyscraper heights, overlaying testimonies on tangible cityscapes actively shaped by the past pronouncements of the person speaking or someone like them. When these people lie or request off-camera anonymity, or whenever Raheb (or, in her quest for information, Saiidi) has to remorselessly cross-examine subjects, Sleepless Nights becomes a film about the difficulties of acquiring and piecing together information. With its obsessive need to filter through facts, discard junk information, and resolve a seemingly untanglable mystery, it made me and colleague/companion viewer Kevin B. Lee separately think of Zodiac. The emotional difference is Saidii’s frequently manifested anger (shouting at Shaftari and an unfortunate archivist, steely and disbelieving when confronted with a British, self-described “adopted Lebanese” shrink who says she can help her work through her feelings) and Raheb’s sullenly manifested determination.

Sleepless Nights was my big discovery for the fest — a major, assured debut conspicuously absent from Sundance, Berlin, SXSW or Tribeca. Computer Chess, my closing film, was an expected highlight. Like Pablo Larrain’s No (also playing the festival), it was shot on archaic video equipment: Bujalski’s from 1969, Larrain’s from 1983. But Larrain’s textures are cruddy consumer-grade video, the kind whose fidelity and tendency to blow out in strong light remained constant and familiar throughout the ’90s. Bujalski’s black-and-white visuals are novel, with an obscure form of analog grain rippling down the screen.

The setting is a three-day computer chess conference sometime in the late ’70s or early ’80s, pitting program against program. One, Tsar 3, seems to be sabotaging itself in the tourney; trying to diagnose it, eye-contact-avoidant programmer Peter Bishton (Patrick Riester) encounters behavior suggesting a computer thinking for itself, possibly knowingly toying with its operators. Inexplicable events occur in the technological realm — a primitive console displays the image of a sonogram when asked, “Who are you?” — and the organic objects world. There’s a hooker floating outside the hotel who could be picking up random customers or keeping sinister tabs on computer engineers interacting with technology the Pentagon covets. The hotel is, for some reason, constantly infested by cats.

The programmers’ technological utopianism — the belief that machinery which masters the calculating functions required to play chess dominantly will inevitably lead to a better society — is mirrored by equally faddish, less prescient period enthusiasms: a vaguely EST-ish hippie seminar led by a genial African of unknown credentials and a couple of swingers who predatorially lure Bishton into their room. “I have to be truthful with you,” the wife purrs. “You could be the greatest chess master who ever lived and still not tap into your full potential.” Her proposed remedy for this lack is group sex, and the terrified engineer flees the room. (The words could also be Bujalski’s acknowledgment of this film as a conscious break in every way possible from his short, excellent body of work, the destruction of a beautifully constructed box that risked pigeonholing his ambitions.)

Computer Chess is bounded only by the ambitious weirdness of its creator’s willingness to baffle, discombobulate, introduce unexpected new elements. Like Alain Guiraudie’s No Rest For The Brave or Alain Resnais’ Wild Grass, it generates suspense partially by making you wonder what Bujalski will do next. During two-shots, a master shot abruptly becomes a vertical split-screen, punching in on a person seated right or left from an entirely different angle — either for emphasis or randomized disorientation, it’s hard to say which (at least on first viewing) — then returning to the full wide shot. Sometimes the POV is a computer screen’s, sentient life staring through a fisheye at the humans trying to harness it. At one point, the film suddenly breaks into grainy, 16mm-looking color, as if Bujalski needs to momentarily revert to a more recognizable style allusive of first and third films Funny Ha Ha and Beeswax.

The weirdness suggests two possibilities — that there’s a larger, probably malevolent/threatening design to everything that’s happening, or that there’s actually no order underlying events at all. Both possibilities are equally terrifying and smack heavily of Thomas Pynchon, whose V., Gravity’s Rainbow and The Crying of Lot 49 tease protagonists with the never-realized possibility of imposing a coherent narrative on the disparate events surrounding them. In 1990’s Vineland, there’s an analogous interest in the role computers could play: in the book’s 1984 setting, they’ve become “Reagonomic ax blades,” used to stop a check by the time a woman gets to a bank at night, having been cut off from her witness protection program. She wonders how that could have happened when the banks were already closed. “The computer never has to sleep, or even go take a break,” the night manager patiently explains. “It’s open 24 hours a day.”

Maybe a paragraph of Pynchon seems unnecessary to flesh out one possible point of structural reference and a shared interest (1984, with its unavoidable Orwellian connotations, is also invoked here as the year machines will beat man). With that note, I’m also hoping to suggest Computer Chess‘ sheer density of incident and potential frames of allusion. There’s heavy shades of Altman in the often impossibly overlaid dialogue, teasing you to choose between two equally hearable possibilities; combined with the barrage of delightfully alienating visuals, it’s a lot to take in. It’s hilarious and totally forward-thinking, probing the many potential meanings of the dawn of an age in which technology’s spread can lead to self-proliferation, anticipating an age where computers are no longer considered optional for a first-world life. Computer Chess is major filmmaking, and made a perfect tonic end to the festival.