Back to selection

Back to selection

Game Engine

by Heather Chaplin

Civilian Casualties

I’ve been reviewing the fourth installment of Gears of War recently, and it’s gotten me thinking about military games. Gears takes place on a planet called Sera and you fight big locusts, so it’s not exactly the U.S. Army, like, say, Call of Duty, but it’s the same basic idea — lots of weapons, lots of choices of weapons and lots of killing.

Now, people are always talking about “violent video games” and the harm they do to young minds, and this drives me crazy for two reasons. The first is simple: video games aren’t violent. They deal in representations of violence, and that may be something you have a problem with, but be clear: it’s not actual violence. It might be a problem, but it’s a different problem. Rugby — that’s a violent game.

Second, as to whether playing games that traffic in violent representations makes you more violent, I’ll say this — you’re barking up the wrong tree.

The instinct is right. But the question is wrong. There is something to be concerned about when it comes to military-style shooter games and being bombarded with these hyper-violent images, but it’s not what you think. It’s not that these games turn innocent babes into violent maniacs. But they are teaching people how to be good soldiers. Play Call of Duty, or Gears of War, and you’re learning skills such as how to flush out a building, how to set up a kill zone and how to work with a squad in a combat situation. I would say you’re being desensitized to images of war violence, which would come in handy, if, say, you were a drone pilot.

All of which leads me to Unmanned.

Capturing a day in the life of a drone pilot, Unmanned is the latest creation from the brilliant Paolo Pedercini and his “radical videogaming project,” Molleindustria.

I ran into Pedercini last month, and I told him I was glad someone like him was bringing a little anger to the indie gaming scene. Pedercini looked at me like I was stupid and said, “I live in a nice apartment in Pittsburgh with lots of midcentury furniture. I’m not sure how much I represent anger.”

Okay, fair enough. Pedercini is now a visiting assistant professor of art at Carnegie Mellon, teaching media production and experimental game design, and presumably has health insurance and other indicators of an upper-middle-class life. But in an industry that remains adamantly apolitical, even on the edges, his work is a breath of fresh air. (Can fresh air be angry?)

Pedercini is from Milan by route of northern Italy. He first came to notice in the U.S. in 2006 with his McDonald’s Videogame, a simulation that has players clearing rain forests, bribing officials and destroying villages. Since then, there’s been Faith Fight (“religious hate has never been so much fun”) and Operation: Pedopriest (“cover-up the sex scandals, restore the faith”) — to name just a few.

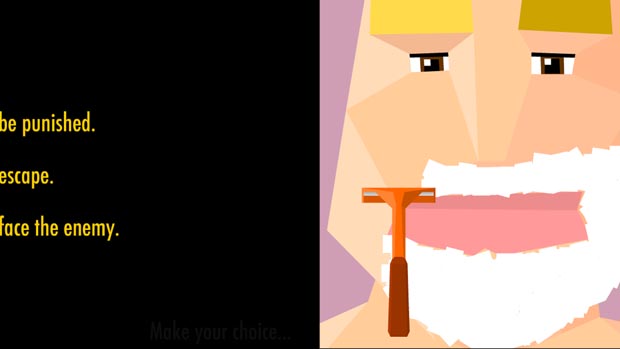

Unmanned is a more thoughtful, more meditative piece of work, though it certainly carries Pedercini’s signature stinging fury fleshed out as humor. It’s an extremely slow game, full of strangely mundane tasks, such as shaving in the mirror, driving on a straight road and smoking a cigarette. Or take the dialog in the game. What happens in Unmanned is to a large extent determined by your choices of the dialogue options. But every time a line of dialog appears, several seconds pass before the flashing “click to continue” appears on the screen. At first you think something is wrong with the game, then you start to think that maybe something is wrong with you for chafing under a slower pace. The game is as much a commentary on video games themselves, and what we expect from them, as it is on American foreign policy.

Unmanned is a day-in-the-life story of a drone pilot done in stylized, blocky, lo-fi animation. We follow him for 24 hours as he has nightmares about being beaten by a member of the Taliban, drives to work, hits on his fellow drone pilot, talks with his wife, plays first-person shooter video games with his son and suffers from insomnia.

In other words, not much happens in Unmanned. You choose from dialogue options whether to be a more thoughtful husband and father or whether to be a total jerk. If you don’t drive your car straight on the road, you get into an accident and miss out on one of the game’s strangest moments, which is a karaoke section to Queen’s “One Vision.” (“One world / one nation / one true religion” and then “One man / one goal / one mission.”) The song takes on a whole other meaning driving down a pixilated desert highway on your way to operate a drone strike.

Almost the entire game is done in split screens. In one case, the action on one half of the screen is shaving the drone pilot’s big blocky face, while dialogue lines on the other half of the screen have you musing about the relationship between shaving and civilization. The split screens create a sense of disconnection — a reflection surely on the schizophrenic nature of being simultaneously an agent of violent death and a father/husband/ordinary guy who shaves in the morning.

Pederici’s aim, he said, was to articulate the American paradox of being bombarded with militaristic entertainment, while studiously ignoring the realities of our wars.

For me, the most interesting part of the game is when you’re playing first-person shooters with your son while discussing his ADHD, what kinds of weapons you have at work and who is worse: commies, Nazis or terrorists. Again, the screen is split — the action is you playing the first-person shooter, aiming for people’s heads as blood splatters the screen — while the conversation takes place on the other side of the screen. It’s funny. It’s horrible. It’s disorienting.

And yes, it’s angry. Even if its maker lives in a nice apartment.