Back to selection

Back to selection

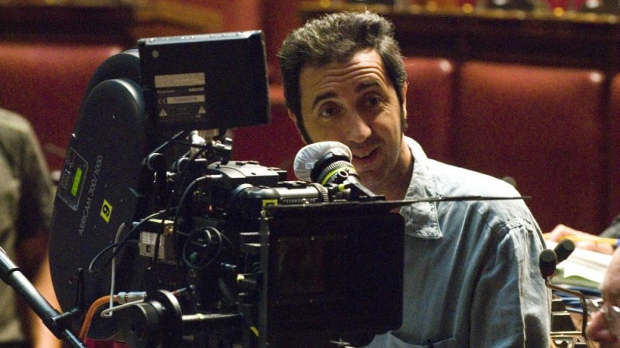

Five Questions with The Great Beauty Director Paolo Sorrentino

The Great Beauty

The Great Beauty Paolo Sorrentino’s latest film, The Great Beauty, premiered in competition in Cannes this year, wowing fans with its over-the-top depiction of modern Rome. Seen through the sad eyes of an aging journalist, Jep Gambardella (Toni Servillo), the film uncovers a series of unsettling scenes where everyone in Rome aims to be an actor on his or her own stage. And Jep is at the center of it all, a man who squandered his writing talents in exchange for a hard-partying lifestyle. He is surrounded by characters too distracted by their urban surroundings to make anything meaningful. Yet behind every image of decadence and decay is a scene of great beauty, as the Eternal City herself takes the title role.

Jep struggles to recover his passion for life, and finally finds it within the city. The film is a wild, long ride, visually packed with indulgent colors and lights. It provides pure cinematic indulgence through a fantastic escape into dark corners and bright landscapes of the fabulous Italian city. Filmmaker spoke with Sorrentino during the festival about his film, which explores his country’s missed opportunities, the fatigue of living and the distracting nature of city dwelling.

Filmmaker: What are we to take from Jep’s failures in life?

Sorrentino: It’s very much a film about the time flowing and with the flowing of time, the time that we end up wasting in our lives. That’s why it becomes burdensome and we are all dealing with the aspect of death. But through this fatigue, this weight of our life on all of us, we somehow give dignity to the life that we are living.

Filmmaker: After watching the film, should we feel happy about the state of Rome today?

Sorrentino: Yes and no, actually. No, because it could be better than it is. And yes, because behind the world, which is portrayed in the film, which is vulgar and decadent and cheap, there is indeed beauty in Rome. But you wouldn’t find it in one day. So if you want to come, you have to spend some time there in order to find the beauty.

I think the film tries to express the present time. That was my ideal of course, and then this is done by reinventing reality and fictionalizing it. But, of course, as often happens through fantasy and invention, you can find truth in a way.

Italy has often been a country with millions of opportunities that have been missed along the way. And that’s why Jep is missing out on his opportunities. He’s wasting his talents and missing out on his life in doing so.

There’s one thing that I like about Rome that was stated by Napoleon: that from sublime to pathetic is only one step away. And in Rome there’s a constant shifting between sublime and pathetic.

Filmmaker: Your films also go quickly from sublime to pathetic. What do you find so interesting in the grotesque?

Sorrentino: I cannot honestly answer that. I don’t know why but I like it. I like grotesque film. It’s like asking somebody why do you prefer white wine or red wine. There’s no answer to it.

But if you think about it, it’s something that we all like at the end of the day. If we had the best ballerina in the world performing in a beautiful dance at the moment, and then she suddenly stumbled and became clumsy, we would all remember that moment when she failed and made herself grotesque and not at her best performance.

So I just wait for people to stumble.

Filmmaker: Director of photography Luca Bigazzi’s images stick with us long after watching the film. What was it like collaborating with him this time around?

Sorrentino: Well, it was a long process actually. I had one idea that was very clear in my mind: I wanted the lights to move in the film. I liked very much this idea. So either the lights were moving or the characters moved in and out of the lights all the time. And it was quite funny to see behind the scenes the director of photography moving around with the lights, instead of having a light source and him moving around.

Filmmaker Magazine: What did you learn from making this film?

Sorrentino: I’m afraid you never learn from experience, but experiences can be very funny. Luckily, from my point of view you cannot capitalize on filmmaking. There’s no connection between what you do before and what you do after. It’s just a simple, single, wonderful experience that has no influence on what you do afterward. That’s my point of view. You can just make films and they become a beautiful memory, but you don’t learn from them.

And I can say because I’ve seen this from experience, that when a director says, “I’m going to do this because I’ve done this already and I know it works,” he’s making a mistake.