Back to selection

Back to selection

Venice 2013 Critic’s Notebook: Gravity and Sorcerer, a Strange Alchemy

Gravity

Gravity While international film festivals, especially those of the calibre and history of Venice (this year celebrating its 70th edition), are most commonly seen as a golden opportunity to catch new cinema from contemporary filmmakers, many offer meaty and mightily tempting repertory programmes loaded with restorations. This year’s Cannes festival, for example, featured restored prints of Vertigo, Hiroshima Mon Amour and Borom Sarret (the first film by a black African: Ousmane Sembene), among sundry others. Venice, as ever, has its own Classics strand, with 29 restorations (and documentaries on cinema), including works by Chantal Akerman, Nagisa Oshima and Satyajit Ray.

However, the extent to which your regular impoverished critic attempting to make a living can indulge in such treats is limited; there’s rarely an opportunity to sell on related interviews for old films, while many of them will have been written about extensively already. Leafing through the programme, I made the decision to catch one restoration for definite: Sorcerer, William Friedkin’s 1977 semi-remake of Henri-Georges Clouzot’s The Wages Of Fear; the digital retooling of which was supervised by the director after a time-consuming lawsuit with co-production studios Universal and Paramount. The 77-year-old Friedkin was in town to receive the Golden Lion Award for Lifetime Achievement, and, in interview, described the film as his “most personal” and “the most difficult to achieve.” In the event, Sorcerer functioned not merely as a bracingly effective slice of sweat-soaked action cinema popping with rejuvenated color, but an unexpectedly fascinating formal, thematic and historical counterpoint to the festival opener: Alfonso Cuaron’s sci-fi drama Gravity.

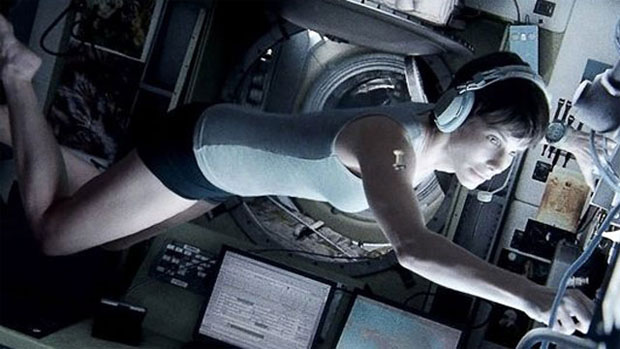

On the festival’s first morning, the cavernous 1,032-seat Sala Darsena buzzed with anticipation before the bow of the Mexican director’s long-awaited follow-up to 2006’s Children of Men. 90 minutes later, the general consensus (myself very much included) was that the film was a real triumph. A technically astounding but refreshingly simple narrative of hope in the face adversity featuring an excellent central performance from Sandra Bullock as a medical researcher adrift in space, it marries visual beauty with genuine emotional and philosophical gravitas. Its most remarkable component is Emmanuel Lubezki’s ever-prowling camerawork; the redoubtably transcendent fluidity of his earthbound work (seen recently in Terrence Malick’s The Tree of Life and To The Wonder) is here transposed to outer space with breathtaking effect; the nearly-20 minute opening scene might be the most tense and beautifully orchestrated sequence I’ve seen all year.

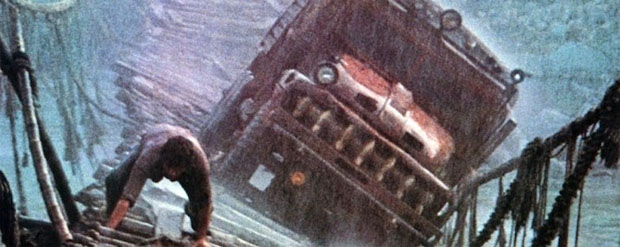

If Gravity represents the cutting edge of innovative, special effects cinema in the present day, then Sorcerer, the last film of three I saw on my first day (Bruce LaBruce’s oddly soft-focus granddad-fetish drama Gerontophilia being the strange meat in the sandwich), is emblematic of a time in Hollywood when budgets were lavished on blowing shit up for real, without the aid of CGI assistance. Sorcerer, which was a disastrous flop upon release, has been seen as the inaugural bloody victim of Star Wars’ runaway success. Lucas’ film, which in itself ushered in a whole new era of SFX magic, opened a month before Friedkin’s, but replaced it again in cinemas almost immediately. A telling quote from Sorcerer’s editor Bud Smith (from Peter Biskind’s book Easy Riders, Raging Bulls) is worth repurposing in full: “When our trailer [for Sorcerer] faded to black, the curtains closed and opened again, and they kept opening and opening, and you started feeling this huge thing coming over your shoulder overwhelming you, and heard this noise, and you went right off into space. It made our film look like this little, amateurish piece of shit. I told Billy [Friedkin], ‘We’re fucking being blown off the screen. You gotta go see this.’” There was something especially fitting about Sorcerer’s close proximity in the Venice programme to Gravity, a film which, like Star Wars before it, could potentially come to represent a paradigm shift in how big-budget science fiction filmmaking moved up a level.

Shot in multiple countries and eventually settling in the harsh terrain of Dominican forest, Sorcerer is, like Cuaron’s film, an often confounding visual experience which frequently prompts the eternal “magic of cinema” question — “How did they do that?” — but for very different reasons. A brief synopsis of the plot (four desperate men must drive two trucks filled with nitroglycerine over mountain dirt roads) is hair-raising enough, but Friedkin ratchets up the tension in pitiless fashion. One scene in particular — the unbearably tense traverse of two trucks over a rickety bridge in the middle of lashing rain — makes you wonder how nobody was seriously injured in the process. With its palpable sense of danger and cobra-like constricting tension, it recalls the likes of Werner Herzog’s thrillingly madcap outdoor escapades Aguirre, the Wrath of God, and Fitzcarraldo. An unexpected corollary of Sorcerer’s visceral power and immediacy was to make Gravity feel retroactively remote; for me, its technical wizardry had faded in the light of the earthy verisimilitude of Friedkin’s film.

The tension brewing in Sorcerer’s globetrotting opening stages was accentuated by a crowd increasingly agitated by an unfortunate subtitling snafu (for about 20 minutes, there were no Italian subtitles for the English-speaking characters). The problem was eventually fixed, but an already surprisingly sparse crowd in the 400-seat Sala Perla cinema shed a stream of disappointed bodies. This was a shame, because once Sorcerer’s narrative direction is established after the first act, it becomes a great example of visual, rather than verbal, storytelling (a characteristic it shares with Gravity). However, one particularly crystalline contrast between the two films is their gender make-up; though both are effectively desperate personal struggles across unforgiving terrain, the sweaty masculinity and inherent violence of Sorcerer couldn’t be further from the strongly female, even feminist, vibe of the Bullock-anchored Gravity.

Both gripping examples of technically accomplished Hollywood cinema past and present, Gravity and Sorcerer made for thrillingly different, but oddly complementary, bookends for my first day at the festival.