Back to selection

Back to selection

Documenting the Life of George Plimpton: Interview with Luke Poling and Tom Bean Part I

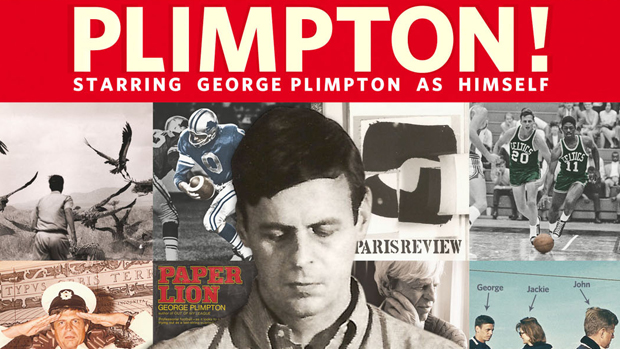

George Plimpton led an eclectic life as a journalist, writer, editor, sportsman and actor, though he was perhaps most widely known for his exploits as a participatory journalist. When filmmakers Luke Poling and Tom Bean set out to make their first documentary, Plimpton! Starring George Plimpton as Himself, they were faced with enough material to make several documentaries. A project like this might have daunted some first-time filmmakers, said Poling, “We’d kicked around the idea of doing one, when Plimpton came up we said, ‘Let’s go for this.’”

Poling and Bean both studied film in college, but first met at a production company in Boston. Poling was PAing on everything from The Departed to Errol Morris’ First Person. “I was fascinated by his work. Documentary was always something I was interested in but had never really done a lot of it because I was on a narrative track.”

Bean later moved to New York where he worked on a documentary about the Iranian hostage crises. “My first real professional writing job was writing Walter Cronkite’s narration for this film,” he says. Unfortunately, the film stalled because of legal issues. Bean then moved to L.A., but stayed in touch with Poling.

Bean was in L.A. trying to write, when the writers’ strike happened. “I was stranded out there not sure what to do. Luke and I had been talking about making any sort of film, whether it be a documentary or a feature, and it just felt right, it felt like the right thing to do,” says Bean.

Filmmaker: Where did the idea come from?

Poling: I was a longtime Bruins fan, and had read Open Net about George’s time with the Bruins. About a year after he died, George’s widow Sarah put out a book called The Man In The Flying Lawn Chair. It was a collection of previously unpublished pieces by George and for me it was like a re-introduction to him. A lot of the material that ended up in the film was in that book.

Bean: I’d seen George in films, but I didn’t really know the extent of his history with the Paris Review. I didn’t really know anything about his sports journalism, and so Luke was sending me books and educating me about who he was. I was like, “Oh my God, we’ve got to make a film about this guy — he’s got such an eclectic resume, his interests are so diverse, he collaborated and knew and friended and was intimate with a number of really, really fascinating people.”

Luke and I are both big Woody Allen fans and we both loved the film Zelig and we thought we could make a madcap documentary about the real-life Zelig, realizing later how different George really was.

Filmmaker: How did you get in contact with the family?

Poling: I looked up Sarah Plimpton in the phone book, wrote her a letter outlining what we would like to do and called her a couple of weeks later. Tom and I went down and met with her a few weeks after that and made the case for why two guys who had never written or directed a feature documentary should be entrusted with her husband’s story. Later on, she said that she felt like this was the kind of thing that George would have done; having some of the upstarts take it on.

Sarah said that she could give us access to George’s archive if we could transcribe CDs and DVDs for her. We said, “Yes, no problem. When can we start?” and she said, “Well, I don’t know yet, I just got these shelves delivered and I need to have them put together and then I need to put everything up on them and sort through them,” and Tom said, “Do you need help putting the shelves together?” The next morning we were in Plimpton’s basement putting together these shelves and getting a first-hand look at what we were going to be archiving.

Filmmaker: How did you finance it?

Bean: Luke and I had written a screenplay together years ago and we had shared it with a few friends and one of them told us that if we ever got a film off the ground we should call him. We called three years later and said, “Hey, remember us? We’re actually ready to make a film.” He became our first angel investor and our executive producer and really contributed to getting us going.

I flew to Boston and literally moved in with Luke and his then girlfriend — now wife — in their little apartment in Chestnut Hill. We just hunkered down and worked.

Filmmaker: It took some time to make this film — how did you manage to keep going?

Bean: There’s this great interview with Francis Ford Coppola where he was asked why he mortgages his house and vineyard every time he makes a film, and he said he always throws himself off a cliff so that then he has no choice but to do it.

We thought it would take a couple of years; I don’t think we thought it would take five. But we knew that the only way we’d get it done is by wrapping our whole lives around making it and knowing that if we did it well it would be an important stepping stone for us as filmmakers.

George embodied so many of the things that Luke and I are personally interested in, and he had such an interesting take on the idea of participating. The idea that he was going to try something and fail, but in failing have this wonderful story to tell his audience. I just thought that his art was a really generous one and one that we can learn a lot from.

Making a film can be really grueling and you can lose steam, particularly when it drags on and on. You’re raising money and you’re collaborating with all these people. Luke and I never met George, but George consistently inspired us, because of his enthusiasm, because of his optimism, because of the way that he would commit and not be afraid. I think that he ultimately became a role model to us as we were making the film.

Filmmaker: Once you had permission, how did you organize the material?

Poling: We had everything from letters from George to his parents when he was in high school, to nearly every invitation or letter he received over the next 70 years. On top of that, there were boxes upon boxes of video tape, audio tape, film footage, even slides. We completely filled up my living room, floor to ceiling. Tom and I spent 6 to 8 months transferring all this footage, and looking at it and that was really the basis for the archival footage for the film.

With documentary you figure it out as you go, the editing is when it really comes together. We knew that we wanted to have George act as our principle narrator. In his writing he was always the star and was known for his after-dinner speaking and lectures, and so we thought it was only right that George should be allowed to tell the greatest story, that of his own life.

We interviewed about 60 friends and family members to get their thoughts and their impressions, partly because there were a lot of things that George just didn’t talk about and didn’t write about, certainly the Kennedy assassination was one that he never discussed openly.

Filmmaker: How did you come up with the style of the movie?

Poling: The first scene we cut together was the Bruins sequence, as we wanted to see if we really could have George narrate the film. We showed it to a couple of friends and it really hasn’t changed that much from then to what’s in the film now. Our goal was to make the film like an adaptation of his writing style, like George was involved in the making of the film, so it had that feeling of reading his stuff. It was that Bruins sequence that really made us feel like we were on to something.

From then on, it was figuring out what the full story was and the best way to tell the story. In the process, you go from a three-and-a-half-hour film down to the 90 or so minutes that the film runs now. It took us a long time.

Bean: I think spending the first year living together, living the film, was really key. I think that really crystalized our take on George; what we wanted to say about him, and where we wanted to go with the project. Once that was in place we could expand our team and start working with editors and have them bring their own ideas to the project as well.