Back to selection

Back to selection

Philadelphia Fire: Jason Osder on Let the Fire Burn

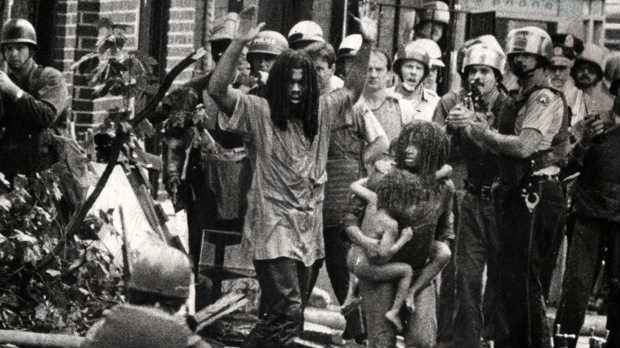

Jason Osder’s searing Let the Fire Burn is a look back at a damning chapter in American history, a moment so outrageous and shameful and multifaceted that all our culture could do was turn around and walk the other direction. A found-footage marvel with no narration and sparse title cards, it dives into the maelstrom that was the Philadelphia police’s tragic raid on the black separatist group MOVE’s West Philadelphia compound in 1985, during which the home, where 13 men, women and children lived, was fired upon 10,000 times, doused with enormous amounts of water and then finally firebombed, an event which led to nearly 70 other homes in the surrounding working-class black community being destroyed. Weaving footage from disparate sources, it creates the impression of being fully immersed in the chaos of that day and the unspeakable terror that visited that misbegotten section of Philadelphia on the day hundreds lost their homes in a groundswell of senselessness born out of the countries’ original sin.

The story is brought to volcanic, penetrating life by Osder, a professor at George Washington University and one of Filmmaker‘s “25 New Faces” of 2013. He used all found materials, chiefly the video record of television newscasts from the day of the assault, a documentary from the mid ’70s about MOVE, footage of testimony from a bi-racial community panel put together in the wake of the destruction to make sense of the affair, and most damningly, a deposition given by a 13-year-old child who lived in the home. That child — who like all the members of agrarian black nationalist commune, which didn’t teach its children to read or write, renounced names given the during the times of slavery and took Africa as his surname — grew up to become Michael Ward, a truck driver who passed away while on vacation last week. He was 41 and was just one of two survivors from the compound.

Let the Fire Burn, which had stops at True/False and Tribeca during its festival run, is now playing at Manhattan’s Film Forum via Zeitgeist Pictures.

Filmmaker: How did you find this material?

Osder: It was pretty much immediately after film school with a guy I met there named John Aldridge, who is an associate producer on the film. I remember him asking me one day, “Do you have any ideas for docs?” I said, “I remember this one incident as a kid that always stuck with me, maybe we should read up about it,” and we did. There was a whole nascent period where we were very slowly producing this film or failing to produce this film. It wasn’t until I started working at George Washington University that I was able to get a bit more traction. We reignited it with institutional support. The project really needed institutional support. I’ve been thinking a lot recently about what that means, especially when thinking about the first period when I very much felt like an outsider. I was asking constantly, “Why won’t anyone talk to me about this very important film, why don’t I get any respect?” The fact of the matter is you work your way up through other channels and you sort of prove yourself and then you leverage that to do a larger project like this. Looking back at it, I see that maybe there is something to that, getting your credentials as a younger filmmaker, even if I resented that at the time. Anyway, you build a network, you build skills, you build your ability to raise funds and get access to equipment and the motivating factor was to make this one film that took an awfully long time.

Filmmaker: How long did it take to make this film?

Osder: There were two periods. One where it was nascent and not going anywhere. That was from 2001 to 2006. I shot interviews and did research in that period. In 2007, I joined the faculty at George Washington University and they came on as a production partner and I gained access to funding and attorneys and a lot of hard resources and broad institutional support. So the second period was 2007 to 2013. I worked on it sporadically before that.

Filmmaker: So just about a dozen years?

Osder: All told. I feel like beyond 10 years it stops being something to brag about. [laughs] It becomes a bit of an embarrassment.

Filmmaker: It’s interesting that you shot interviews for the film. It’s all archival, found footage now, yes?

Osder: Yeah. I didn’t set out to make a found-footage or all-archival film. For a long time, my model was One Day in September. I never wanted to shoot interviews with everyone who had anything to say about this, but just a select few people whose lives this really affected. I interviewed Ramona Africa, I interviewed some cops, I interviewed the late Michael Ward, the kid as an adult. When I did that I thought it was the exclusive and would make the film. It was a story you had never seen. I wanted to interview Wilson Goode, the mayor, but I never got that interview. I think I could have gotten it eventually but by the time I could have I didn’t want it. It was in the editing room with the editor Nels Bengerter that we felt the potential to tell the entire story in present tense with the archival footage. The potential of those hearings was to do the sort of thing you’d do with the talking heads or the narrator, move the story forward and provide context, but without the liabilities of popping the cork and taking all the tension out of your film. I think talking heads have a lot of authority in your film unless you’re going to do the Errol Morris and have them hear the questions. The way you set that up you generally give them a great deal of authority. So the thing about the hearings is that we could do everything we wanted to do but we didn’t have to give anyone that unquestioning authority because they’re always being doubted and questioned. We thought it was a risk but if it worked we thought it would be something special. We thought we were way out on a limb but since the film has premiered there has been a couple of notable films that have some variation of this approach that involves sticking with the archival materials more than is traditionally acceptable. We’re thrilled to be part of that movement. We were scared to be out on a limb.

Filmmaker: You grew up in Philadelphia?

Osder: Yes, I grew up there.

Filmmaker: Was there footage you found that you thought was compelling in its own right, perhaps because of its colloquial, Philly-centric quality, that didn’t for whatever reason fit into the story you were telling?

Osder: Sure. Lots of stuff. There was a lot more wild news stuff for instance. I love the moments where the news breaks down — a scene starts with a familiar convention: the on-scene commentator, but then when they start ducking bullets and whatnot, the familiar frame breaks. I think that is emotionally effective. We could have cut scenes like that all day.

Filmmaker: Once you decided to go down the archival-only route, did you have any particular models concerning all-archival, found-footage filmmaking that you were leaning on when conceptualizing this film?

Osder: Not really. What’s interesting to me is that we made the decision to try to cut an all-archival film about three weeks before The Black Power Mixtape 1967-1975 premiered at Sundance. We thought we were way out on a limb with this approach, but in fact it turned out we were part of a nascent movement. I had of course seen Atomic Cafe and some other classic examples, but I did not set out to cut an all-archival film. Rather, there were certain emotional and intellectual goals that I wanted to get out of the story and, with help from editor Nels Bangerter, I realized that the best way to achieve those goals was an all-archival approach.

Filmmaker: What do you personally make of MOVE’s ideology? Was it difficult to fully represent in the film given the footage at your disposal?

Osder: I actually think my point of view is well represented in the film . . . so, I’ll leave it at that.

Filmmaker: Have you encountered any especially extreme or unusual audience reactions?

Osder: No, not really. I thought the film would make people more exercised, even angry, but in fact the reaction seems to be more contemplative. Questions are thoughtfully presented, even if they are challenging. Some smart people who watched the film early seemed to understand that it would work this way with audiences; it didn’t click for me until the first public screenings.

Filmmaker: Michael Ward passed away last week. Had he seen the film at the time of his death? Had you had any communication with him recently? There is certainly a dark and powerful irony given that his story is being retold with the release of your film.

Osder: Yes. Our team is stunned. Michael had not seen the film and I had fallen out of touch with him some years ago when his attorney David Shrager passed away. You see David briefly in the film. He was an important person in Pennsylvania legal circles and represented Michael pro bono from the time of the fire until his death. Frankly, a week after learning this news, it is still reverberating for us on any number of levels. We are presenting the opening screenings of the film in Michael’s memory. On a panel last week, someone made a point that I hadn’t yet thought of; Michael’s untimely death cuts one of the strongest remaining connections to this history and particularly what happened at the end in the back alley. Thus, a story that seems perpetually receding into the fog of history is hastened in that direction. It is, like the entire affair, a tragedy.