Back to selection

Back to selection

“Everything Seems to be Licorice”: Land Ho!’s Martha Stephens and Aaron Katz on Shooting in Iceland

Land Ho!

Land Ho! Land Ho!, co-written and co-directed by Aaron Katz and Martha Stephens, is an odd-couple two-hander like Katz’s previous Cold Weather and Quiet City, and a progressively rural odyssey like Stephens’ Pilgrim Song, accented by the hues of regional color familiar from both directors’ palettes. But given the film’s Icelandic setting, perhaps another frame of reference is also called for. In interviews, the filmmakers frequently discuss the remoteness of the Icelandic landscape, its incongruity with the day-to-day lives of their characters, and, above all, its mysterious and “otherworldly” beauty.

In Iceland, where I currently live, this view is not necessarily reflective of the day-to-day attitude, but there is at least a strain of the national cinema, predating even the country’s reinvention as a tourist destination with Blue Lagoon ads plastered over the A train, that acknowledges the objectively bizarre and epic qualities of our geographical heritage. As a document of spiritual tourism following a foreigner’s journey deeper and deeper into an engrossing but perhaps opaque Icelandic landscape, Land Ho! recalls Friðrik Þór Friðriksson’s Cold Fever, and in setting two dudes on a road to nowhere, with their petty problems juxtaposed against the formidable Icelandic landscape, the film also recalls Á annan veg, recently remade as Prince Avalanche by Stephens and Katz’s executive producer David Gordon Green.

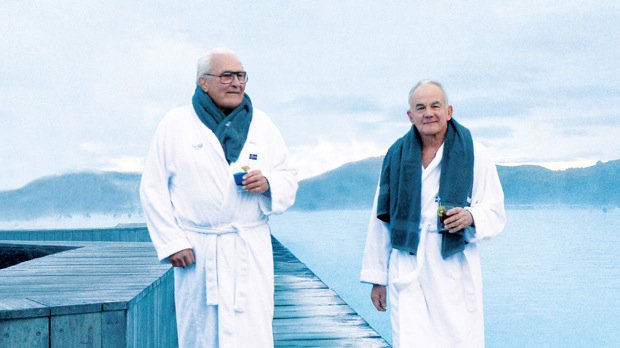

In Land Ho!, ex-brothers-in-law Mitch and Colin (Earl Lynn Nelson and Paul Eenhoorn) take a trip to Iceland, encompassing Reykjavík, the Golden Circle and south coast, and the Landmannalaugar highland area, followed by a brief coda at the Blue Lagoon. Though hardly a smash-and-grab microindie with a shoestring crew, Land Ho! was made on a more intimate scale than the studio mega-productions which have lately discovered Icelandic locations (Oblivion, The Secret Life of Walter Mitty, Noah, etc.), and differs from them in actually being set in Iceland. What we see on-screen reflects the product’s inspiration — Stephens was reading up on Iceland to plan a vacation — as well as the visits that constituted the pre-production and production phases, and makes the film an interesting case study in the interaction between visitors, filmmakers or otherwise, and a new place. The film opens tomorrow from Sony Pictures Classics.

Filmmaker: You talk about the remoteness and strangeness of the landscape, and the incongruity of your actors here. Did Iceland become less strange in the time that you were here and shooting here, or did it remain this sort of exotic place?

Stephens: Yeah, I think it remained a mysterious, exotic place. There’s just something so enchanting about it. Not in our five weeks there did we think of it as a regular place. There’s no way.

Katz: Especially once you’re outside of Reykjavík. Reykjavík’s a really great city, but in some ways it feels not too different from other Scandinavian cities. But once you’re outside the city — even on the Golden Circle, which is the Geyser and Gullfoss, which are the big-ticket items that most people who are there for a few days would go see — but those things are genuinely so incredible. I feel like I could watch the geyser go off 100 times and it wouldn’t get old. And then when we got in even deeper, into the real countryside, the real wilderness — even to get from our hotel to where we were shooting was an hour-and-fifteen-minute drive over what was hardly a road. So [Iceland] really didn’t lose any of its mystery, for us.

Filmmaker: It feels like the film is in part dependent upon a sense of Iceland and a sense of place, and when you’re capturing that for a film, how do you strike a balance between trying to be authentic to the place — not having, you know, the equivalent of a bunch of Eiffel Tower cutaways in a film set in Paris — and on the other hand, the fact that these guys are tourists, are visitors, and this place is exotic to them?

Katz: I guess we really tried to view it as tourists. We’ve talked a lot about how in the past, Martha and I have both made films about places where we’re either from, or living at the time — in Martha’s case West Virginia and Kentucky, in my case Portland and New York. We were outsiders here just as the characters were, and we tried to approach it as though we were tourists, in a way: what would they focus on? And I think, because of the nature of the story, it was appropriate to do it that way. Nothing in Iceland is as instantly recognizable as the Eiffel Tower, but if the movie was about Paris, I think we would probably have a bunch of shots of the Eiffel Tower. There’s a few different things that made Iceland appealing. One is that the obvious tourist stuff is actually really fun and cool, and it’s kind of a funny idea that they’ve read one guidebook, and that’s what they’re gonna go to. Another is that Iceland is this Iceland is this beautiful and majestic place, and contrasting that with the jokes.

Stephens: The whole movie, we’re trying to bring opposing forces together, so they’re on a black, crazy, otherworldly road, and they’re talking about Julia Roberts.

Filmmaker: In the time that I’ve been here, I’ve had visitors who are jetlagged and lose their first day to sleeping, or get rained in, or take day trips to the wrong sorts of places, I was relieved that in the movie they seem to have a pretty good itinerary on this trip. They even get a rental car that they can take on the F roads inland. What was it like, logistically, planning a film shoot that was also a vacation, on-screen at least?

Stephens: It was hard, because I’m a location scouting fanatic, it’s such a huge part of pre-production for me, and if I had had it my way, I would have taken the guys all over the damn country, gone up to the fjords and stuff. It was hard for me to rein myself in, and be like, all right, we can only stay on the southern coast, because it’s practical. I’m going to butcher this, we call it “Land Man a Logger,” how do you say it?

Filmmaker: I say it that way, too. [But, in fact, “Landmannalaugar” is pronounced: “land” to rhyme with “wand,” “mann” like a short Teutonic “mahn,” a short “a,” “laug” with the difficult one-syllable ascending “oy-guh” sound which the letters a-u-g make in Icelandic, and a softly piratical “ar.”]

Katz: The Icelanders demonstrated for us so many times how to say it. But no matter how many times they did it, saying it the way they said it made me feel like saying “Paree” instead of “Paris.”

Stephens: I got distracted. I was talking about how I had to rein myself in while location scouting, which was hard.

Katz: — And we really wanted to have three different kinds of —

Stephens: — environments.

Katz: Yeah. So we have the city, we have the main tourist out-of-the-city stuff, and then we have some real off-the-beaten-track wilderness stuff. It seemed like a good structure for the movie that they get further and further away from civilization, and maybe as they get further from other people, they get closer to each other.

Filmmaker: Planning a shoot for a film set in a foreign destination, did you have a lot of flexibility once you got here? What we see onscreen seems pretty close to a feasible itinerary, there weren’t many liberties taken [in writing or post-production] with the geography.

Katz: We tried to keep it pretty real, really the only thing that’s totally bogus—

Stephens: Jökulsárlón, right? [The glacial lagoon, a couple hours further east, which the characters visit prior to returning to the capital region to fly home.]

Filmmaker: How much more was there in the way of logistics beyond the hotel rooms and rental cars we see on-screen? Were you a large crew?

Stephens: Not really. I feel like our crew was about twelve? Thirteen people? It very much felt similar to the way we conducted crews with our previous movies.

Katz: For example, in Reykjavík, the actors were staying in a hotel, but the rest of the crew—

Stephens: — were in like a Real World-style house.

Katz: It was very Real World.

Stephens: Everybody had a bed except for [producer and A.D.] Sara [Murphy], who slept on the couch.

Katz: Poor Sara.

Filmmaker: You did an Airbnb?

Stephens: We did. It was a great house in the neighborhood near the church [Hallgrimskirkja, the downtown Reykjavík landmark]. On our days off, it was great, we could walk to Noodle Station, and go buy our sweaters.

Filmmaker: Iceland is trying very hard to attract foreign film shoots. From what I can tell the economic initiatives seem mostly geared towards large-scale studio products and corporate ads. Are you getting production rebates, did you seek Icelandic funding or anything like that?

Katz: The producers would be better suited to answer this question than us. But yeah, we worked with Icelandic co-producers who helped us with that landscape. Of course we’re a lot smaller than Oblivion, or Interstellar, or other [American] movies that shoot there, but I think they’re really set up to encourage movies at all levels. It’s somewhat uncommon for a movie of this scale to shoot there, but it’s a good place to shoot, and like you said, they’re trying to encourage production, so they have a lot of infrastructure—

Stephens: — But that’s gone now, right? Didn’t they stop? [During the Land Ho! shoot, Iceland’s new center-right governing coalition released a budget which proposed a 40% cut to the budget of the Icelandic Film Fund, which subsidizes domestic production, effectively keeping local film professionals employed between visits from Hollywood studios]. We had two guys on our crew, like 19-year-old guys who wanted so badly to make movies, they’re really great, and were sort of heartbroken.

Filmmaker: You were actually along the south coast at the same time that Nolan was shooting Interstellar around Kirkjubæjarklaustur. Were you aware of that while you were here?

Stephens: We were very aware. Sometimes we couldn’t get equipment because Interstellar had all the equipment. At one point when we were in the highlands, we were staying at the same place that the B-roll unit was at.

Katz: Once you’re in the highlands, your housing options are extremely limited. We were in really the only place within an hour or two of this area. Calling it a hotel seems like a generous description.

Stephens: It was a place where there were like three levels of rooms you could have. There was the more dormitory wing, we were in, then there were the more hostel-like accommodations that had bathrooms, and then there were the nice rooms. Those guys from Interstellar were staying in the legit nice wing of this place.

Katz: It was the kind of place that really felt like it was at the end of the world, like when you see pictures of Antarctic research stations.

Filmmaker: How much of your crew was Icelandic? What sort of local support did you have, and were you encouraged to take on local crew here?

Stephens: We thought we would have more Icelandic crew, but it just turned out that we couldn’t afford Icelandic crew in a lot of cases. They were used to being paid more than we could pay, so it was cheaper for us to bring over, like, our ACs, and our sound and all that. But we did have Icelandic co-producers, who set us up with Arnar, our locations manager. The movie didn’t really have a production designer or anything, but we had a props person, and then the two guys who were our camera PA and grip.

Filmmaker: It’s interesting, there are actually very few Icelanders on-screen.

Katz: Especially for older gentlemen like [the characters], a lot of times when you travel to another country, you’re so isolated from the life that goes on there usually. When you go to all these tourist destinations, you run into people from other countries. That is a conscious choice.

Stephens: When I went to Iceland, other than the people who checked me into my hotel, or a waiter, I didn’t meet any Icelanders, I met tourists all the time.

Filmmaker: This is all sort of linked to the other major economic initiative of the last several years, in addition to film production, which is tourism. There’s a scene where your characters read aloud from the Lonely Planet writeups of two restaurants where they eat and where you shoot. How was it working with the hospitality industry in Iceland?

Katz: Honestly, the interaction wasn’t that different than what we would have done in the States. We just called them up.

Stephens: I don’t think anyone was like, “Oh yeah, please shoot at my place because I think this is gonna be great for my business,” I think that they were just being nice. We don’t have any big-name actors, we don’t have a big budget.

Filmmaker: When you discussed your project with Icelanders, what sort of responses did you get?

Stephens: Really no-questions-asked, just kind of nice and pleasant. No one seemed to pry too much…

Katz: Happy to help, but also, like, “You guys do your thing, I’m cool, whatever.”

Filmmaker: Did you have any encounters while you were here that made it into the film, or that you were tempted to write into the film? How spontaneous did you allow yourselves to be with that?

Stephens: As we were going along, not so much, we had a tight schedule. But I went on my location-scouting trip before, so I incorporated things that I experienced at that point into the script.

Katz: During pre-production, for example, we had had the encounter that they have with glowstick guy [a drunk local at a bar who gives the travelers glowsticks] written into the script, but weren’t sure what path to take with casting that. We had gone out to a bar called Dolly, and this guy was the bartender there, and we were like, “This is the guy.” We tried to be open to stuff, but once we actually were shooting, we really tried to keep things pretty focused. Like Martha says, the schedule did not allow us a lot of leeway. And I think that’s a good thing, to keep things focused.

Stephens: On my trip, I experienced the two-percent beer, I bought a beer [in a supermarket] and thought it was real beer [as the characters do].

Filmmaker: Downtown now, they have flyers advising tourists not to be fooled by the light beer.

Stephens: Well, I was fooled.

Katz: Well, let me ask you something — I think we’re about to get cut off here, but I have one question for you, which is, what do you think of the licorice and chocolate combination, which Icelanders seem to love so much?

Filmmaker: Um, you just have to know that that’s what’s coming. You’ll go to like these self-serve soft-serve places where you spoon out all the toppings. You just have to slow yourself down when you’re digging the spoon in, to know that, if it is licorice, that you know and that that’s what you want. That is the biggest thing.

Katz: Everything seems to be licorice. I feel like anything in Iceland, it could be licorice, no matter what it looks like. Candy bars, weird little things that look like they could be some kind of blackberry gummy treat — nope, probably licorice.