Back to selection

Back to selection

The Last Days of Collapse Subject Michael C. Ruppert

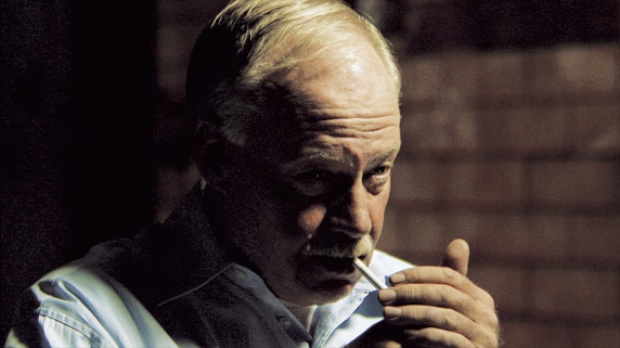

Michael C. Ruppert in Collapse

Michael C. Ruppert in Collapse The life and final days of Michael C. Ruppert — author, 9/11 Truther, podcaster and prophet of economic collapse — are chronicled by The Verge’s Mat Stroud in a fascinating, quite sad story. Filmmaker readers will remember Ruppert from Chris Smith’s 2009 documentary, Collapse, in which the author discussed his theories of societal collapse in the decades following “peak oil” — the moment in which there is less oil in the ground than has been used by mankind.

For Smith, however, the documentary was as much about Ruppert the man as his work. In an interview with Brandon Harris, Smith said:

Ultimately I was interested in making a character study about a guy who’s dedicated his life to these issues. He’s spent thirty years coming up with this theory. To me, the film was about who he is and how he ended up here and the effect that this process has had on his life. I personally wasn’t interested in making a movie about energy or sustainability or food or overpopulation or economics. There are so many of those films that have come out over the last couple of years. I find that they can feel somewhat educational. I find Michael to be an incredibly entertaining person. His philosophy, the way he looks at the world, is more unique than anyone I’ve ever met. That was what we wanted to focus on, on him. We wanted to make a character study as opposed to an issue driven movie. The issues are there and for you to understand him I think you have to understand why he thinks these things are going to happen and what his theory is.

At The Verge, Stroud documents Ruppert’s life story, from his days on the L.A. police force to his independent media investigations into the CIA’s role in the Nicaraguan drug trade to his participation in Smith’s film. Collapse garnered Ruppert a larger audience, which he parlayed into a website, CollapseNET, but soon he became burnt out on the end of times. From The Verge:

In 2012, he moved to Crestone, Colorado and divested from CollapseNET — a move driven by financial struggles, as well as his belief that “multiple ‘systemic’ failures in human civilization … cannot possibly be reversed in this world as it currently operates and approaches crises.” By 2014, he had divested from pretty much everything else, too. Wes Miller — a lawyer and friend who represented Ruppert following the FTW sex harassment debacle, and then helped build CollapseNET — said the onetime hellraiser “didn’t want to fight anymore. He just wanted to do his thing, work on songwriting, and move on to a different life.”

The rest of the piece, which traces Ruppert’s employment tangles, depression and, finally, suicide, is a striking portrait of man whose sense of doom — stoked by mental illness — became more than academic. I was struck by this section where Ruppert looks forward to a media opportunity he thinks will re-introduce him, post-Collapse, to the public:

A week earlier, a production company filming a presentation for the channel H2 flew Ruppert to the Seattle area for on-camera interviews. Ruppert thought the opportunity would be perfect — a means to re-legitimize himself in the mainstream five years after Collapse. Instead, he was disappointed. The first-class treatment, the attention, and the people he encountered made him feel hollow. “It was a daunting experience,” he told his podcast listeners — like “I was in the Matrix.” Everyone he encountered was “going through the motions of what they do in their life.”

In the airport, waiting for his flight home, “I didn’t see a smile anywhere,” he said. “Everybody looked gray, they looked dead, they looked like robots, like they were going through motions…. My perception was that the reality of the collapse of human industrial civilization — or the reality of their reality — is disintegrating in front of everybody.” Later, he said, “There’s a leadenness out there in the world right now that weighs on us like a blanket.”

Ruppert shot himself on April 13 in Calistoga, California. He took great pains to leave notes and send emails so that his own death would not become conspiracy fodder for his still significant audience.