Back to selection

Back to selection

That’s Funny, You Don’t Look Jewish: The 2015 New York Jewish Film Festival

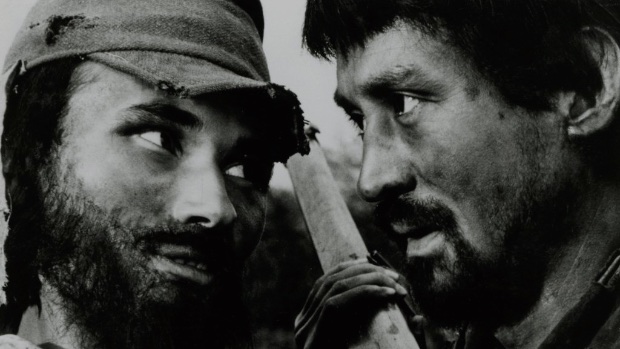

Fires on the Plain

Fires on the Plain I was appalled by a posted comment on this site about the title of my coverage of last year’s New York Jewish Film Festival. A pun on a seminal German novel, “How Jewish Is It” was to me not just incredibly clever but apt. I felt the festival’s mission admirably expansive compared to some earlier editions and sister events in other cities. The commenter, who self-identified only as “The Judge,” felt differently: “How Jewish? Give me a break! Everything about movies is Jewish, or did I miss something?”

Lo and behold! The Judge’s snarky observation was prescient. I had commended festival director Aviva Weintraub, of producing institution the Jewish Museum, and other members of the selection committee for both the festival’s scope and quality. Weintraub (unavailable for an interview at press time) remains head, her fellow deciders back in place, save for a change in the one rep from co-presenter the Film Society of Lincoln Center.

A comparison of film rosters from the current and last festivals, however, indicates a significant shift. A number of this year’s sidebars and titles do not just stretch the already-loose definitions of Judaism, Jewishness, and Judaica, they bypass them altogether. Anything can fit, force-fed if necessary into unwelcoming tags. The choices push not only the envelope but the mailbox along with it. The NYJFF appears to be diluting its unique identity on the path toward a more comfortable fit into the world of non-specialized general fests. I think of the famous advert from yesteryear, “You don’t have to be Jewish to love Levy’s real Jewish rye.” Is the move a welcome increase in breadth or suspect pandering for acceptance?

Of the large number of films (out of 47 features and shorts) that broach the subject of assimilation, Russian director Alexey Fedorchenko’s Angels of Revolution provides a model for exploring the metamorphosis. In this anarcho-surrealist exercise based on an actual episode in 1934 known as the Great Samoyedic War, Jews do not resist the melting pot. The USSR’s Peoples Commissariat of Ethnicities exports a band of avant-garde artists and thinkers, nonconformists themselves and many of them Jews, to seduce through Art–the great unifier–the Khanty and Nenet tribes in the Kazym region in the far North. They have nixed the government’s demand for cultural collectivism that runs afoul of their ancient traditions. Friendly persuasion proving to be unproductive, the authorities resort to force (more about the film below).

The analogy with the 2015 festival is that the agenda of a new curator at the Jewish Museum, Jens Hoffmann, is upsetting a tenuous balance. Jewish is barely de rigueur. He has more power in the hierarchy than any of the official selectors. Continuing the metaphor, defiance against him and the older powers-that-be on the board would prove pointless.

An outspoken, highly regarded art-world maven, Hoffmann was appointed last year deputy director of the museum and director of the NYJFF’s special events. His stamp marks some of the spurious items on the menu—and for him that might be a sufficient requisite for inclusion. He revamps the auteur theory, which posits that the director is the defining figure whose signature brands even the most confined studio films, into an axiom that exhibitions and their organizers are the markers by which trends can best be observed and judged. I can’t help but wonder: Is moving away from makers in the direction of connoisseurs, critics, or administrators eager to make their imprint the wave of the future?

Oy weh iz mir!

His choices and generous responses to my e-mail queries suggest questionable methodology.

Unable to wrap my head around the section “War Against War,” which is his baby, I ask him to elaborate. Godard’s Les Carabiniers? Kon Ichikawa’s Fires on the Plain? Peter Watkins’s The War Game? I understand that these are contemporaneous films. But in the Jewish Film Festival? Sha-lom! Is it a function of the ongoing conflict in Israel or a commentary on the eye-for-an-eye vendetta ingrained in Jewish culture?

He writes:

It started with my desire to show the first movie (Fear and Desire) of one of the most important filmmakers of the twentieth century, Stanley Kubrick, who is Jewish, on a big screen. The movie is rather little known. This film happens to be an anti-war film, and the overall series is about his film in relation to other iconic anti-war films of that period.

These are all anti-war films that do not focus on the spectacle of war but more on the inner workings of the characters and the defeat they experience, even though their army might have won a battle or the war. The ultimate line here is that in war there are not winners, only losers, as the individual trauma is more profound than any victory of a country over another could ever be. Besides Kubrick, two of the other directors featured, Gillo Pontecorvo (The Battle of Algiers) and Konrad Wolff (I Was Nineteen), were also Jewish.

Some trivia, for the record: Kubrick was born into a Jewish family in the Bronx but did not practice. Whether he had a yiddisher kop I can’t say. When few cinephiles knew that Mike Leigh (the family had been Lieberman) was Jewish, he told me that once you know, you see it in all his films. Is this true for Kubrick? As for Konrad Wolff, his father was Jewish. When Hitler came to power, his Communist family fled Germany for the Soviet Union. Following the war, he settled in East Germany. (His brother Markus served as intelligence head for the notorious STASI.) And Pontecorvo? He was in fact Sephardic, an Italian Jew—good to know in the case of a film about the war in Algeria from which thousands of Sephardim chose or were forced to leave after the French departed.

Hoffmann’s sentiments are noble, but I still don’t understand the congruence with the NYJFF. The line of argument triggers an aural flashback, the comedy album “When You’re in Love the Whole World Is Jewish” that my yiddishe mama in Texas played to my horror for my Southern Baptist high-school buddies.

The Judge just might be a sage.

I received telling responses about the inclusion of “New York Noir (1945-1948)” from Hoffmann and Rachel Chanoff, longtime head of the festival’s selection committee. The strand is comprised of three chilling thrillers — Robert Siodmak’s Cry of the City, Henry Hathaway’s The House on 92nd Street, and Jules Dassin’s The Naked City — and A Child of the Ghetto, a restored silent short by D.W. Griffith. According to Hoffmann:

New York Noir is a tribute to classic Hollywood crime and noir of the ‘40s and ‘50s. Film noir, just like the western, is a purely American genre that has had a big influence on the history of filmmaking in many parts of the world. We like to explore film genres, such as the anti-war film this year, or sci-fi in 2016. Many of the most iconic films in the noir genre have been directed, written, or at least produced by Jews.

Produced? The Judge must be grinning like the Cheshire Cat.

A seasoned programmer, Chanoff’s worldview and knowledge of film and Jewish history are thoroughly entwined:

[The sidebar is] a mix of Jewish directors and a theoretical, Jewish sensibility about the dark, pessimistic possibilities of life. Is New York City a Jewish city? Are dangers lurking around every corner a constant reminder for the Chosen People? Hmm….

Between the lines of her answer I read World War Two and the Holocaust. You can add prewar movements, like German Expressionism in film and other arts, which, interrupted by Nazism and the war, were reincarnated in the States as noir. Jewish emigres played a tremendous role in bridging the gap.

Finally, I asked the most important question of all: “What constitutes a Jewish film festival?

Says Hoffmann:

In addition to the main program, the sidebars allow us to look back, explore certain directors, writers, or actors more, look deeper into very particular approaches and ideas of directors, and look at ideas related to filmmaking such as the Saul Bass poster and opening credits exhibition last year… The additional programming reflects how we work at the Jewish Museum in general. We do not only look at one particular artist or niche but do a larger overview of the context around the people and subjects we work with.

I wish I could say I get it. When I try to deconstruct the answer, I come up with bupkis. How is the Saul Bass exhibition an idea? Approaches, overview, context: generalities and abstractions full of a bureaucrat’s sound and fury, signifying ein bissel.

By e-mail, Chanoff responds:

Every year, as we begin our curatorial process, we ask ourselves, What is a Jewish film festival, and why do we think that it’s important to have one? With so many festivals crowding the cultural landscape, what makes a particular slate of films, when seen together, constitute a worthy exploration of a theme? Each season, we strive to deepen the definition: from the most obvious — Jewish characters, Israel, and/or historical Jewish events — to a broader perspective.

We are interested in investigating Jewish ethos and core tenants like tikkun olam (“healing the world”), Jewish humor that has infused itself into the culture beyond us Jews, and historical situations where Jews have played a major role, though the situation itself was not necessarily notably Jewish.

Jewish- and film-specific. She asks rather than pontificates. In a single paragraph, she paints a general picture, then offers examples that convey the seriousness of breaking it down and a sense of the knowledge needed to do so.

This discussion of the New York Jewish Film Festival is not just a single case study, but rather a point of departure for assessing institutional priorities, or defining group shows and exhibitions, or prerequisites for the delicate task of choosing who’s in and who’s out. Can an approach used to evaluate one medium function for another? The age-old question “what is art?” becomes more complicated when artists move between media, even more when they appropriate developing tendencies from the domain of the digital.

Genug. To the titles. Leaving aside films in the sidebars, in deference to the core program, my must-sees are listed below:

Jerusalem of Gold Blintz

Felix and Meira (Maxime Giroux, Canada)

Pity the Hasidic wife (see Fill the Void, Kadosh). Scratch that. Pity the Hasidic wife, the Hasidic husband, the Hasidic infant, and the goy in mourning who lacks structure but nonetheless upends their otherwise foretold destinies. Quebecois filmmaker Giroux (Jo for Jonathan, Sophie) spreads empathy all around. He and regular co-screenwriter Alexandre Laferriere don’t divvy them up into good and bad: All are products of circumstance.

The film begins in the charmless apartment belonging to unreservedly pious Shulem (Luzer Twersky), a tall man whose peyas hanging alongside his ears and high, cylindrical hat defining his sect belie his youth, and his even younger, unfulfilled wife, Meira (Hadas Yaron), whose schadel and matronly wardrobe can not mask her angelic beauty. It’s soon obvious that the two share little besides religious identity and a beloved baby son. Meira is by tradition mostly homebound, save for religious functions and an occasional push of the stroller through the mixed Hasidic, Greek, and artsy-hipster Mile End section of Montreal. During one of these promenades, her customary rest stop inside a kosher bakery becomes the setting for a blink-of-an-eye frisson between her and Felix (Martin Debreuil), an agitated man in his mid-thirties from outside her circumscribed community. We realize that this woman with major reservations is a candidate for a momentary rush; we learn that he is wide open for it, his estranged father lying at death’s door in a mansion around the corner.

The remainder of Felix and Meira tracks not only their budding relationship but also the fading one between the spouses as well and the rivalry between these radically different men. Settings shift from Montreal to the busy sidewalks of New York City and finally to the romantic, touristy spots of Venice. Connections alter according to locale. Cinematographer Sara Mishara, who has worked with Giroux before, captures the prevailing mood in each place, most impressively in gray Montreal at the height of winter and on an East River ferry with multiple windows reflecting the state of the affair.

Giroux is a master of the lengthy ellipsis, with which he frequently takes a pass on depicting relatively high dramatic moments. Forcing us to fill in the substantial gaps helps pull us into these peoples’ worlds, especially the closed society of the Hasidim. He is so brilliantly attuned to Meira and Felix’s opposing rhythms that we buy into their mutual attraction from start to finish.

Sterling Silver Blintz

Let’s Go! (Michael Verhoeven, Germany)

Cripples limp about in yet another picture addressing the topic of assimilation, a poetic German made-for-tv one-off that, according to Verhoeven, could only get made and broadcast by a veteran filmmaker like him. Members of a Jewish family reside in the country postwar. The entire mishpocha is traumatized: the Eastern European-born parents, from years in the camps; the children, from the projected anguish of the survivors. The malformed people they encounter are likable gentile manifestations of a torn social fabric through which a small number of fortunate Jews has kept wandering after liberation by GIs, whose snappy commands inspire the title.

The principal subject is the mutable bond between 21-year-old Laura (Alice Dwyer), a lapsed Jew who returns from L.A. to her native Munich upon the death of her father in 1968, and her middle-aged mother (Naomi Krauss), who, even while sitting shiva disparages her for abandoning the faith. No matter that Mutti and Vater had tried to pass as non-Jews and had taught their two daughters to deny it outside the house. In Verhoeven’s view, hypocrisy was a necessary part of the postwar Jewish experience, even if it exacerbated problems for damaged individuals. Vater chides preteen Laura for eating ham, but gets admonished by her and her younger sister for sneaking pork into their kosher home.

Compounding the schizoid identities of these youths in public denial are anti-semitic verbal attacks from peers and more vicious ones, like the swastikas the family discovers painted on their new car. Their dad is the most troubled family member: Although he sometimes beats the girls, he still confronts a gentile schoolteacher who dares discipline Laura with a slap on the hand; and he behaves frightfully to a blond man who has courageously saved the girl from drowning. He refuses to be indebted to non-Jews, who are judged by a different set of standards.

Let’s Go! is also about Laura’s coming of age. We learn about her maturation against a background of the family’s attempts to cope, which are relayed in flashbacks to the late’40s, mid-’50s, and mid-’60s. (Period production design by Christian Kettler is both accurate and superbly executed.) Her growth and the family’s maladjustment are inseparable, most notably when Laura falls in love, twice. One boyfriend is the Jewish kid next door, a reminder of the shtetls, where a limited gene pool resulted in marriage between relatives; the other, one of the handicapped, a handsome, polite upper-crustian who has the misfortune of being non-Jewish. “What did your father do during the war?” Vater asks with a scowl when they first meet. Mutti does not back her up. What chance does this relationship have?

Metro-Grand Jewry Prize

Angels of Revolution (Alexey Fedorchenko, Russia)

As impressive as it is, Angels is convoluted, chaotic: The rewards are in the fragments. It is magical like Fedorchenko’s great Silent Souls (2009), but less restrained. Polina (Daria Ekamasova), based on an actual historical figure, leads the brigade of aesthetes and intellectuals from their precarious perches in the city to the remote northern tundra. We get each of their back stories, in no way linear. At the outpost, they articulate their ideas and display examples of their media for a visibly disinterested indigenous population. Any assumption that they will accept the superiority of uniformity over their own mindset and colorful ethnic displays holds no water.

Fedorchenko and d.p. Shandor Berkeshi treat us to a widescreen bouquet of diverse theatrical and film productions, musical performances, and lectures about functional inventions by the visitors, as well as the creations, rituals, and icons of the Khanty and Nenets. The latter are unimpressed, but the natives’ art and symbols touch the outsiders, and us. Maybe art is universal: The output on both sides is remarkably similar.

The most riveting sequences are from a film-within-the-film by Pyotr (Pavel Basov), a director based on Eisenstein. He shows the tribespeople footage nearly duplicating Que Viva Mexico! After the gang tricks their way onto a sacred island overseen by shamans where cats are both honored and burned, he projects onto the rising smoke, which resembles a dark, imagery-laden whirlpool. The surprised tribespeople are now impressed. Fedorchenko’s narrative is guess-proof.

Tongue on Special Prize

The Mystery of Happiness (Daniel Burman, Argentina/Brazil)

Brotherly love gets a humorous spin in this latest specimen of superior craftsmanship by Burman (Lost Embrace). Timing is everything in his and Sergio Dubcovsky’s savvy script and Luis Barros’s precise editing of Daniel Ortega’s crisp widescreen images, but even more so in the unforgettable comic performance of wide-eyed Guillermo Francella, who plays Santiago, a platonic-lovelorn bachelor.

For this loyal schlemiel, Eugenio (Fabian Arenillas) is more of a tight sibling than a buddy. They are doubles: Setting up the equation is an impressive initial montage in which the two are mirror images of each other, like Lucy and Harpo in a famous old tv sequence. For his part, though, Eugenio faces a no-brainer: on the one hand, to spend the remainder of his life selling household appliances during the day with Santiago and the evenings as a sounding board for a pill-popping wife with logorrhea; on the other, to follow a repressed dream — a word oft repeated — that necessitates his unannounced disappearance. Narrativus interruptus.

The second half follows the adventures of Santiago and Laura (an overplaying Ines Estevez), Eugenio’s abandoned wife, who replaces her husband in the office. They have to work out whether or not to sell the company. Burman broadens her part to Santiago’s after-hours companion. They both have to know what happened to Eugenio. Pasha, an obese poseur of a private eye reminiscent of Sydney Greenstreet who holds court in a restaurant decorated to look like Rick’s Cafe Americain in Casablanca, provides clues vague enough to be valid, but sufficiently tangible to secure payment of his bar and food tab.

An observation Pasha shares about male friendship leads Santiago and a newly transformed Laura, placid and sexy, on a search for the man in their lives at a downmarket Brazilian seaside resort where the two fellows had sewn their wild oats many years prior. What they find calls into question the pact of renunciation the men had made should rough patches test the intimacy of their connection. Burman borrows from the comedy and romance playbooks — this is an Argentinian bromance, after all — with some fun results. Like the musical score, the film has bounce.

One Kid, One Kiddush Cup

Gett: The Trial of Viviane Amsalem (Ronit Elkabetz and Shlomi Elkabetz, Israel)

This is a contemporary domestic update of the ancient debates between uncompromising Talmudic scholars, except that three religious-court judges are in full accord. They refuse to negotiate with the titular woman, an Orthodox wife who tries for five years to acquire a gett, or divorce decree, from an unwilling husband who holds all the cards. Only the male counts. In Israel there is no recourse to civil divorce, or civil marriage for that matter, so that anachronistic theology dictates the outcome.

Set entirely in a spare, white-walled courtroom, this third and last film in a trilogy is as claustrophobic as the marriage between plaintiff Viviane (Ronit Elkabetz, who acted in Late Marriage, Or, and The Band Waits, and who co-directs here with brother Shlomi) and stubborn defendant Elisha (Simon Abkarian). This pious man from rabbinical stock in his native Morocco still loves his wife despite their long, bitter separation. The conditioned product of strict Jewish laws regarding gender relationships, he refuses to relinquish his claim. No agreement, no divorce.

Frustration is the structuring absence. Viviane sits quietly each time the judges put off the matter for months–until she breaks. She damns the court with language so vulgar that she is banned from the premises. But her anger goes deeper: It has a strong sexual component. She adheres to religious tenets so has no affairs, despite accusations made by morose Elisha and his shameless lawyer. But an unspoken attraction heats the air between Viviane and her handsome, charismatic lawyer, Carmel Ben Taven (Menashe Noy). Elisha’s unwillingness to grant her a divorce is only secondarily a function of religious belief. Endowed with a typical male ego, he fears she will hook up with another. He can not abide anyone else sleeping with her.

The couple can’t even agree to disagree. As the saying goes: two Jews, three temples.