Back to selection

Back to selection

Sundance 2015, Dispatch 1: Best of Enemies and Eden

The Best of Enemies

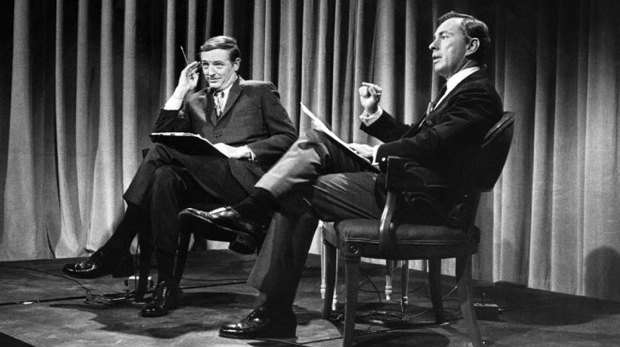

The Best of Enemies Morgan Neville and Robert Gordon’s documentary Best of Enemies, premiering at the Sundance Film Festival, details the particulars of the eight televised debates between William Buckley Jr. and Gore Vidal held on ABC in 1968 — four during the Republican convention in Miami, another four during the infamous Democratic one in Chicago. A very prototypically Sundance-y doc (destined for TV and classrooms, “audience-friendly”), this is a consideration of an Important Topic fleshed out with contextual talking heads and zipped up into a brief, digestible package. Given sufficient interest in the subject, it’s the kind of thing I’d generally watch on Netflix and only there, since these docs tend to be lacking in formal properties. Another problem with this kind of work is that access to the primary materials isn’t exactly lacking: the debates are there in full on YouTube for those who want to watch them.

But surprisingly, Neville and Gordon display an above-average interest in adding something of their own. Their brief character sketches of Buckley and Vidal come to a head with a clip from the notoriously unloved film version of Myra Brackenridge, with Vidal’s delightfully terrible heroine hovering over a patriarchal nemesis with a cigar. The shot is a low-angle one looking up at her, and Neville and Gordon promptly cut to a reverse shot of Buckley that’s exactly where it would be in the movie — neatly (and visually, rather than through over-explication) aligning Vidal with his disruptive heroine and Buckley with her appalled victim. This is, as far as I can tell, a pretty fair encapsulation of the interpersonal dynamics at stake. Other above-and-beyond plusses: zippy graphic animations livening potentially static magazine pages, choice outtakes from the ABC News archives (Sam Donaldson junkies, this one’s for you) and a nicely eccentric selection of Baroque music (broad enough to include both Switched On Bach and the Barry Lyndon arrangement of Handel’s “Sarabande”), justified by both the general fustiness of the tenor of debate and some amusing footage of Buckley playing Bach at the harpsichord.

The documentary makes a twofold argument. The first is that the Buckley-Vidal debates were fun to watch: two over-educated, effortlessly patrician men with eccentric verbal styles dueling at length, serving as perfect antitheses for each other. This kind of televised rhetoric doesn’t exist anymore — for one thing, says linguist John McWhorter, this kind of speaking style would now be considered “unfeeling” — but it directly led to an unintended consequence: ABC, struggling in third (out of third) place in the news sweepstakes, benefited immensely ratings-wise from these gladiatorial combats, and TV news’ swift degeneracy into shouty pundit faceoffs soon followed.

This second argumentative prong isn’t unreasonable, but the documentary paints itself into an ideological corner. Concluding that talking heads shouting at each other is bad is, politically, a pretty neutral argument, and unexceptionable neutrality is exactly what this doc is going for, but there’s something else going on here. Presented merely as a linguist (which he quite notably is), McWhorter is also the author of Losing the Race: Self-Sabotage in Black America and more on the Buckley side of things; presenting him onscreen as just a linguist is a bit evasive in this context. Also onhand: Sam Tanenhaus (former New York Times Book Review editor and a noted conservative himself, the latter not acknowledged onscreen at all), fleshing out the argument that Buckley helped the Republican party to discover a new constituency in disaffected whites and that ideological debates are inseparable — indeed, interchangeable — from cultural debates. This isn’t a good thing from where I’m standing: it’s the kind of thinking that poisons this entire country. With his conspicuous locquaciousness and eagerly displayed erudition, Buckley presented a (certain kind of) civilized face for some rather brutal ideas: his legacy, if anything, grows more toxic by the day as his eloquence is stripped away and only the rot beneath it remains.

It strikes me as deeply suspicious that both McWhorter and Tanenhaus — not to mention Lee Edwards from the ultra-right Heritage Foundation — are presented on-screen as neutral voices rather than people with very particular points of view and reasons for caring about this topic. (Balance, I guess: Todd Gitlin’s also on hand.) In its homestretch, Best of Enemies trades its early momentum for footage of the 1968 DNC police beatings scored to ominous music (the sonic equivalent of triple-underlining something that’s already in bold caps) — something unambiguously Sad. But — as fun as it is to watch Vidal’s pro-caliber condescension or Buckley’s sneering pronounciation of the last three syllables of “Myra Brackenridge,” his voice disgustedly sliding down — it’s a little difficult to stomach a long lament for the decline of mass-TV white patrician argument as such. When a doc like this settles for a shrugging lament for the decline (from such great heights?) of American political debate, it’s suspicious to give some of the final words to Tanenhaus, who laments that we have become “communities of concern” on particular topics rather than a unitable nation. That may sound reasonable, but it also sounds like just another lament for the decline of hegemony. Given that Buckley and Vidal were talking about the very fault lines that have only been growing by the day, it’s ultimately weird to elevate them over the topics they discussed, mourning the loss of some mythical age of unitary concern rather than worrying about the reasons for this national fragmentation. I might be being oversensitive, but blandish docs like this one shouldn’t be given the benefit of the doubt.

Another fond look back, this one much more open about its biases, comes in the form of Mia Hansen-Løve’s fourth feature, Eden. The nostalgic fetish object here is French house, and the movie is unavoidably very different now than it would have been even two years ago, simply because in the interim Daft Punk finally had an honest-to-goodness ubiquitous monster single (they got lucky!). A subject which once would’ve been a bit niche-y now has a mass market point of reference, a sad irony for its primary point of anti-identification. Paul (Félix de Givry), a DJ whose story is loosely based on Mia’s brother/co-writer Sven, floats through 131 minutes essentially unchanged, for better and worse: he was there when it all started but got left behind, confined to the marginalia for crate-diggers to recall.

The narrative is divided into two labeled parts, “Paradise Garage” (after the late NYC discotheque) and “Lost in Music” (after the Nile Rodgers-produced Sister Sledge period), spanning November 1992 to 2013; the period-placing title cards are very specific, with a touch of a deep music lover’s fact-oriented pedantry. During that time, Paul doesn’t lose his looks or reorient his interests at all. At first, that’s a good thing: his dedication to a new sound gets him in on the ground floor with fellow enthusiasts, propelling him up the globe-trotting DJ circuit. Mom isn’t thrilled in the early going, and never stops being suspicious: “Did you see Le Monde?” she asks. “There’s an article about ecstasy,” and she’s worried, since “all we need is a homo with AIDS.” Shades here of the winking triumphalism of someone who knows their side will prevail in the culture wars, but this pocket of music is definitely in my wheelhouse, so I’m not bothered. I appreciate the presence of not just Daft Punk throughout (first acknowledgment: “Who are they?,” a nice joke about their career-long penchant for anonymity), but even the presence of “Quentin,” for those who care that Mr. Oizo (aka Quentin Dupieux) was also around.

Paul doesn’t turn out to be either Daft Pink or even Mr. Oizo, and when he catches up with an ex (Greta Gerwig) in New York, she marvels that “it’s crazy that you haven’t changed.” The movie avoids heavy gray-hair makeup and other indications of the passage of time, which is preferable but opens up another impossible problem: Boyhood aside, how does one plausibly age people on-screen over the course of decades? In interviews, Hansen-Løve contends there are some subtle markers onscreen, but I’ll confess they passed me by. I’ve heard the argument that this lack of aging represents the confidence of those who want to be eternally young, which doesn’t wash with me but I’m noting it for the record.

Regardless: constant cocaine use will take its toll — maybe not physically, but certainly fiscally, and as Paul sticks to his DJ guns and refuses to update his tracklist, he finds himself barely clinging to self-sufficiency. (A club manager’s appraisal is both pragmatic and fun if you hate where big club music has gone: “David Guetta isn’t your thing. I understand.”) By film’s end, Paul has finally accepted that his time has passed, but there’s one final cruel irony, when a girl at a writing group responds to his profession of interest in garage music with “The only electronica I listen to is Daft Punk. So, what is garage?” Paul was there with them at the start, but she has no idea why that matters to what she likes.

With its massive soundtrack, pretty players, and Hansen-Løve’s characteristically fine eye, Eden can’t help but be amusing. Nonetheless, for me neither this nor her previous Goodbye to Love clicked. In her first two films (All Is Forgiven and The Father of My Children), she started from the perspective of a troubled/semi-absent father, then interjected a violent rupture in their lives — heroin addiction and suicide, respectively — and redirected attention to their daughters, both as affected by these events and as autonomous teenage women coming of age. These elisions — a wise refusal to try to explicate and literalize nearly unfathomable extremes of emotion and behavior — were models of concision and judgment, and the films were no less emotional and impactful for them. Like Eden, Goodbye was a family affair (loosely taken from her own life), and in both cases the writer-director seemed to have lost any ability to pick and choose. In Goodbye and Eden, years pass and seemingly nothing can be left out: every little event is deeply important. Hansen-Løve remains someone whose work should be eagerly anticipated, but this particular trajectory unnerves me.