Back to selection

Back to selection

“Awful!” vs. Applause: Terrence Malick’s Knight of Cups

Knight of Cups

Knight of Cups When it was announced late last year that Terrence Malick’s Knight of Cups would be in competition at the 2015 Berlinale, many read this as a sign of hope – that the festival could still manage to snag a world premiere that most would assume was destined for Cannes. At the other end of the scale, there were those who, sight unseen, took this as confirmation that its unspooling here is a telltale sign that the film simply must be second-rate.

That divide was as evident at the finale of Sunday’s press screening, where the first sound heard in the packed 1600-seat Berlinale Palast during the end credits was a cry of “Awful!” followed by a healthy dose of hearty applause, but nowhere near the thunderous rapture that was reported on social media. Yet even the die-hardest of Malickites (Malickians?) can understand why the film will prove to be even more divisive than his previous two.

From both an aesthetic and thematic perspective, Knight of Cups is a curious amalgam of The Tree of Life and To the Wonder. The vast barren landscapes and god’s-eye view of Earth from TOL are there, as are the images of childhood, difficult father-son relations, dead-sibling issues and matters of a spiritual nature. The take on relationships (twirling included) is straight out of TTW, and in ways that film feels like a proof-of-concept for this far more ambitious work.

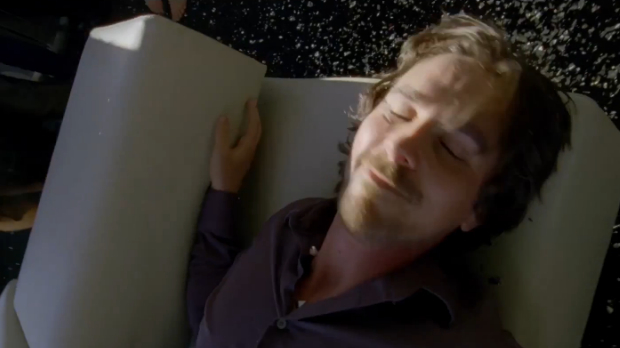

Knight of Cups’ plot, if you can call it that, is centered entirely around Rick (Christian Bale), a Hollywood screenwriter who has lived and loved la dolce vita but is now suffering from a lack of meaning in his life. The titular knight, whose tale we hear in voiceover early in the film, sought a pearl from the ocean and drank from a cup that erased his memories of possessing royal blood. We hear this tale from Brian Dennehy, who plays Rick’s father, an aged actor who appears to have a troubled relationship with both Rick and his other son Barry (Wes Bentley). As most scenes of dialog are quickly faded out and replaced by music, we can only glean the details (lip-readers take note) but it’s clear a dead brother factors into it all.

As a superficial character to the extreme, it’s unsurprising that Rick’s drug of choice for spiritual healing is women. In several chapters (named after individual Tarot cards) we witness fragments of these relationships – actresses, strippers, models, ex-wives, wives-of-others portrayed by Natalie Portman, Imogen Poots, Freida Pinto, Isabel Lucas, and Teresa Palmer, to name a few. In between, Rick navigates the Los Angeles landscape (stunningly captured by dp Emmanuel Lubezki), which includes decadent parties, fashion shoots, the beach, his minimalist apartment, and swimming pools. Lots and lots of swimming pools. Nothing is lingered on for very long, nor is the camera ever at rest. Characters are introduced, and then disappear suddenly – one can only imagine what the metaphorical cutting-room floor must look like. Trademark shots, particularly those of Bale in nature, contrast with images and locations we’re just not used to in a Malick film: a drunken party montage, the interior of a strip club, the boulevards of Las Vegas, etc.

The depiction of women, who for the most part function as window dressing to Rick’s crisis, could turn out to be the film’s Achilles heel, and many words will no doubt be penned about objectification and the male gaze. Though contextually it fits with the self-centered hedonistic world that Rick is trying to escape, it remains problematic. Still, there’s so much to process here. Symbols to be decoded, ideas to be parsed, images to reflect upon – a review written just hours after seeing it is bound to be lacking. Sure, the spiritual-lite aphorisms that appear in voiceover at times border on cliché, but to outright dismiss the film isn’t doing justice to the genuine pearls to be found within this challenging masterwork.