Back to selection

Back to selection

Jazzed: Asif Kapadia’s Amy

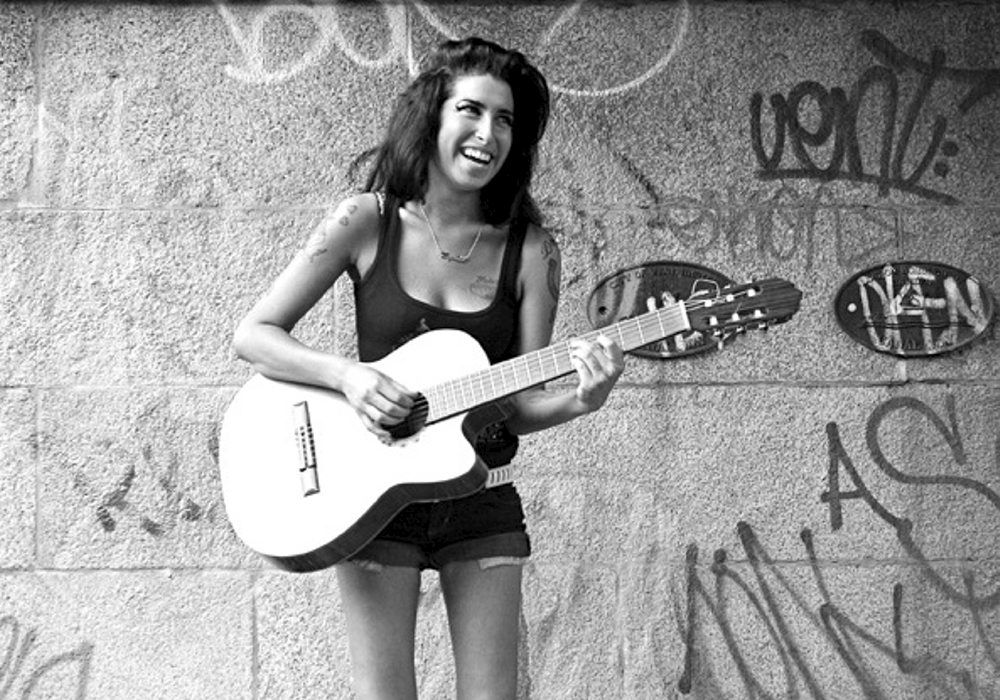

Amy Winehouse in Amy

Amy Winehouse in Amy When it came to music, Amy Winehouse forcefully played dual roles, as much master as slave. She had a tough time separating the two. As a young teen in the barely middle-class Southgate section of London, she was under strict instructions from older brother Alex, who constantly played music in his room, never to enter without knocking. Otherwise, she said, “He would throw things at you.” One time, however, she could not stop herself, and stormed in without permission. Dumbfounded, he imagined an emergency. “What’s this?” she asked, pointing to his record player. “It’s Ray Charles,” he answered. “’Unchain My Heart.’”

She left his private sanctum and proceeded to play Ray Charles “exclusively” for the next three months. Needless to say, obsession (musicians, drugs, bad boyfriends included) was high on the list of her major psychological issues, such as bulimia and depression by the age of 13, massive alcohol intake in her early teens, cutting, and violent behavior when her willfulness spun out of control. (The director of Amy, Asif Kapadia, claims she was bipolar but never diagnosed.)

The embodiment of simplicity, she was neither extravagant nor affected. In 2004, radio journalist Jonathan Ross gave her what he considered a compliment on his program: What he liked about her was how common she was. In Maurice Linnane’s excellent post-mortem 2012 doc about an intimate concert and interview she had given in 2006 in St. James Church in remote Dingle, Ireland, Amy Winehouse: The Day She Came to Dingle, editor of the Irish TV series Other Voices Philip King reflects on her short visit: “We all knew that we were in the presence of greatness, but when she first arrived we sort of tiptoed around her, not knowing what to expect. But all she wanted was a packet of crisps.”

She did not seek fame. At the beginning of Amy, the thorough, masterful new doc by Kapadia (Senna), she says, “All I want is to have the freedom to work with people I want to work with, to go to the studio when I want to.” For love of the art, she had begun early on to polish her considerable gifts. The words to her original songs were personal poetry, her almost freaky modulating voice (coming from a bone-thin 5’3” frame held up by the spindliest of legs) equally comfortable with jazz, pop, blues, soul, and reggae.

Had she lived in a bubble, there might have been hope for the shy, funny Jewish girl. But she didn’t. She got away ASAP from the disjointed, dysfunctional family she held responsible for her problems, which only became worse after she began sharing a flat in Camden with a girlfriend. She took an assortment of jobs: entertainment journalist for the World Entertainment News Network, performer at Russian clubs and casinos.

After she became featured female vocalist for the National Youth Jazz Orchestra, her professional career took off. Once she achieved name recognition, following the 2003 release of her debut album Frank, marketers, paparazzi, and all shades of gold-diggers converged on the solitary soul, demanding even more disclosure than her heartfelt, uncensored music revealed.

Her honesty demanded a persona, psychological and physical, that matched her artistic bent and the powerful influences she credited. Not easily pigeonholed, she fragmented herself. She did it with songs — bad-girl ditties (she adored the girl groups from the ‘60s, like the Shangri-Las, who made her giggle with the line, “then a miracle: a boy,” from “I Can Never Go Home Anymore”). She did it with skimpy clothes, a few facial piercings, and a slew of tattoos. And she did it with her trademark Ronnie Spector-like mascara, heavy red lipstick, pronounced eyebrows, and her signature beehive (a weave), a relic of the ‘50s and ‘60s.

She was hardly original. Former Rolling Stone editor Joe Levy called her a knowing collage. Mitch Winehouse, the father to whom she was unhealthily attached and who divorced her mother when Amy was nine, precipitating her initial downward spiral, has claimed that she also came under the spell of the Latinas she saw in Miami Beach when she went to work with musician Remi Salaam.

Master and slave came into conflict. Music was an inescapable magnet for her, but at the same time, she feared that “the more people look at me, the more they’ll see I’m only about the music.” She saw that as a negative. I beg to differ. It’s a positive, a commentary on the integration of person and art. Kapadia counters the downer tone with lots of shots of her writing music, the camera moving into extreme close-up to superimpose her face on the page. He discovered how to penetrate her unique complexity. “The answer is in the lyrics,” the Indian-English filmmaker told Kaleem Aftab of The Independent, adding that Amy is his Bollywood moment, a movie in which song lyrics are key.

He inserts clips of her singing some of the stronger, if better-known, ones.

Now my destructive side has grown a mile wide

What is it about me?

The odds are stacked

I go back to black.

I died a hundred times

You go back to her

And I go back to black.

For you I was a flame

Love is a losing game.

What a mess we made

And now the final frame

Love is a losing game.

The words chart her love life, most of which was spent in the company of Blake Fielder-Civil: party boy, addict, former bouncer, and archetypal codependent, who introduced her to hard drugs, interfered with her stints at rehab, and ended up in prison. (Interestingly, the lyrics “poured out of her” following her divorce.) She was clearly cognizant not only of her emotional pain but of her deteriorating state of mind and body. Close friend and former manager Nick Shymansky (she engaged him after exiting a different agency for the crime of repping the Spice Girls) says that the late-night TV hosts who had once welcomed her with open arms went into a “feeding frenzy. It was okay to make jokes about bulimics and crack/cocaine poisoning.” She needed at minimum a long break and more rehab than she was getting (she was a terrible patient), but performing is what she knew. She began to arrive on stage drunk and occasionally forgot the lyrics. On several occasions she was booed off; other times, she marched off mid-song.

Besides, those closest to her, like Fielder-Civil and her opportunistic taxi-driver/ex-wall-panel installer father (“Don’t make a mug of me. Why are you bringing another camera crew?” she asks him during an extended stay on St. Lucia), were enablers who did not want to slow the substantial cash flow. Her mother, Janis, was pretty much out of the picture. (Winehouse claimed that her mum was not very maternal, and in fact it was her “nan” — her paternal grandmother — who had been the source of her strength.) Her manager, Raye Cosbert, a man who did not know when to stop, thought it a family matter, her parents claimed she was an adult responsible for herself (although the situation got so bad Mitch eventually had her involuntarily committed).

Two devoted longtime pals, Juliette Ashby and Lauren Gilbert, were the only ones who saw where the trajectory was leading and urged her to take rehab seriously, even to leave the business. Russell Brand tried to convince her to check herself in again. Ultimately they gave up and distanced themselves; after all, Winehouse was so immersed in chemicals that she had sacrificed everything that had been dear to her, including friends. They did, however, prove indispensable to Kapadia during the making of Amy.

Winehouse not only wrote and sang beautiful lyrics: She manipulated with them. While recording a duet with her “idol” Tony Bennett (“Body and Soul,” for his Duets II album) — among those she revered were Sarah Vaughan (“her voice is a reed instrument”) and English artist Soweto Kinch — she would demand to repeat them over and over again to allay her nervousness; after all, she had become clean in order to do the recording, which turned out to be her last.

“Everything you need to know about Amy Winehouse is in her singing,” adds King in Amy Winehouse: The Day She Came to Dingle. “Her heartbreak, her vulnerability, her strength, her attempts to overcome her demons, her exultation at being able to write a great song….Here was a woman who had been touched by people like Mahalia Jackson and Ray Charles, absorbed it all, and came out sounding like herself — new and authentic, adventurous yet traditional. She rang very true.”

Kapadia, who had the blessing of the Winehouse family until they saw the completed film and felt that it assigned them guilt in her decline and death, includes archive and concert footage. (Amy was fully financed by Universal Music Group, parent company of her outfit, Island Records, and Kapadia retained artistic control.) Fortunately, Shymansky gave him 10 hours of video he had shot from the early days of her career, much of which is well integrated into the film.

A lesser known side of Winehouse is that, very possibly under advisement by minders, she dabbled in business ventures, mostly lending her celebrity and occasionally creative input to clothing lines, greeting cards with lyrics from her songs, and all things Fendi. (Might she have thought these were salves proving she was not only about her music?) She also performed for huge sums of money at private functions for Russian oligarchs, depressingly allowing one to choose her repertoire. Her parents, who inherited her entire estate, have kept the brand going. Mitch published a book, My Daughter, Amy, with all proceeds benefiting the Amy Winehouse Foundation they control, with brother Alex an employee. Let it be noted that her own record on charitable donations is commendable; she was known as a soft touch.

Her death at 27 is widely considered to be from alcoholic poisoning. The British coroner gave as the cause misadventure. Alex is sure that it is the result of a lifetime of bulimia. She had also developed early emphysema from smoking crack/cocaine so heavily. Whatever the ultimate cause of her demise, Kapadia lays it out for us with photos and sound from beginning to end.

Many contemporary female singers, Adele and Lady Gaga included, have expressed their gratitude to Winehouse for leading the way for alternative acts for women, and for helping remove the stigma of vintage from new versions of pop music. Bennett told Jon Stewart, “She was the only singer that really sang what I call ‘the right way,’ because she was a great jazz-pop singer. A true jazz singer.”

Soon after she died, Bennett said, “She should be treated like Ella Fitzgerald and Billie Holiday. Life teaches you how to live it if you live long enough.” Possibly the most troubling, and cautionary, tribute came from Reverend Mairt Hanley, vicar of the Church of St. James in Dingle: “Great art came from her on the edge. But it doesn’t have to stay on the edge.”