Back to selection

Back to selection

Mother Load: Xavier Dolan’s Tom at the Farm

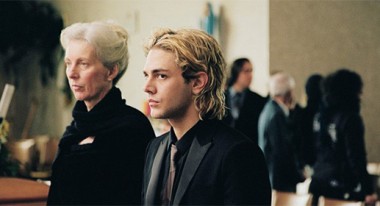

Pierre-Yves Cardinal, top, and Xavier Dolan in Tom at the Farm

Pierre-Yves Cardinal, top, and Xavier Dolan in Tom at the Farm I have the romantic’s weakness for tales of thwarted opportunities in the relationship department. Saddest and most frustrating are those for whom faulty communication, intentional or otherwise, generates the lion’s share of the blame. Ever read Poe’s short story “The Purloined Letter?” It involves theft, blackmail, a woman of royal lineage — it’s opiated Poe, what do you expect? — but we Little People can suffer in our more ordinary ways from the exchange of tainted information. I use the word exchange purposely: The action pains not only the victim, but the perp as well.

Quebecois director Xavier Dolan puts his finger on the process at the beginning of his excellent psychological thriller, Tom at the Farm, an adaptation of Michel Marc Bouchard’s minimalist, four-character stage play shot before the more recent Mommy but only now getting a U.S. release. Dolan opens things up just enough in the film — a few minor, additional people, road travel, some locations off the farm of the title rather than the play’s three farm sites — to retain the graceful spareness and claustrophobia that runs through. (Dolan wisely includes some massive, mostly unused interior spaces for dramatic counterbalance. This aesthete knows how best to light an empty barn for a sexy tango between two men who despise each other.) The heavy, and heady, through-lines about death, memory, and masterful manipulation remain intact.

The film opens with a close-up of a hand and an elegant pen writing out in royal blue ink on a white table napkin what appears to be an intimate note along the lines of a cathartic diary entry.

Today, a part of me has died, and I cannot cry

For I’ve forgotten all synonyms for sadness

All I can do without you is replace you.

The text encapsulates the feel of the movie as it unspools. It is loving and emotional but cynical nonetheless, bluntly honest to the point of what most of us would consider tactless, so practical in its expressed need for self-preservation that it becomes callous. I am pretty sure these are Bouchard’s words, but from what I know of Dolan and his films, they might as well be his. Of course, Dolan chose to make a film from Bouchard’s work, and the two co-wrote the screenplay.

Without warning, the writer, the eponymous Tom (a dyed-blond, long-haired Dolan with wire rims), ceases the flawless penmanship with a voiced-over, “Fuck this!” He begins a drive from his hometown of Montreal to the isolated Quebecois farm where work and reside the remaining family members of his recently deceased lover, Guillaume, just as they always have. Setting the correct tone are what he encounters once he reaches his destination: sad gray skies and an empty home devoid of warmth. The prodigal queer who got away returned only for his church funeral, where Tom will be the only attendee from outside the tiny rural community nearby.

The handwritten note turns out to be only the first segment of a complicated but fascinating structure. Taken in total, it is part confessional, part eulogy for a recently departed lover that, owing to clever narrative tweaks, does end up serving an epistolary function. Like a moveable literary feast, the threads resume, but now they are verbalized.

Tom recites some of what he had written and adds to it. His audience is comprised of the young, sorely missed subject’s mother, Agathe (Lise Roy), a simple woman afflicted with early dementia whose behavioral timer is already out of juice, and older brother Francis (Pierre-Yves Cardinal), a muscular vessel of animal magnetism with a gray-matter count out of normal range who fiercely protects her — even if inventing false scenarios and carrying out unspeakable acts of violence are mandated in his unevolved provincial mind.

In no way will Francis take the risk of his sheltered mother’s discovering that presumed favorite Guillaume was gay, possibly bi, and that Tom, an uninvited guest, was his boyfriend. No matter that Maman doesn’t bother to pretend to show affection toward her surviving child. Francis leaps into his cover-up project. He builds a prison around Tom. He creates for his sibling a girlfriend, Sara (Evelyne Brochu), a real-life copy girl in the lovers’ shared ad-agency office and close friend of Tom whose name he had heard when the visitor spoke to her on the phone.

We can predict that it is only a matter of time before Sara appears, yet another of Guillaume’s circle pushed into playing the pretend game, but she is a slave to truth. She is also stronger than her male peers (as women are in Dolan’s films), and cannot keep to herself her feelings about the hypocrisy of Tom’s participation in the web of lies that Francis has concocted.

Francis has a photograph his brother sent of him kissing Sara passionately. She notes that just as Guillaume lied to his family about his sexual orientation, he was dishonest with Tom. Her elaboration becomes a game-changer. Instead of a spoiler, here is a line from the play that Dolan told an interviewer is of great importance for him, although it had to be cut from the film: “Before learning how to love, homosexuals learn how to lie.”

With the transition from written to spoken word, everything, from mood to fact, changes. The prose remains frank but is no longer elevated. In fact, the language becomes much more vulgar, with bodily fluids and parts normally unexposed tossed off democratically. Hurtful to those gathered, it is full of falsehoods and half-truths that nearly cancel out the purer emotions of the earlier portion.

During this time, the characters undergo major alteration, almost as if they are memes in Tom’s prose. He himself is no longer a lonely soul seeking a shared pity party who showed up unannounced. He and the kinfolk, very different specimens, have had a reciprocal effect on one another. He purposely passes up opportunities to escape his cage. Even though he knows that Francis, especially, occupies physical and cultural space far from his urban, intellectual, and very gay lifestyle, he starts to adapt to its difference.

The falsehoods he utters, many of them forcibly planted by the bestial, disapproving Francis, are elements in this nasty example of Stockholm syndrome (Tom defends Francis and his reprehensible acts) and its reverse manifestation (Francis moves back and forth between pushing Tom away and pleading that he not abandon him). Captor and captured have begun to trade some of the other’s retooled consciousness until the full dynamic goes into reverse gear.

For once the music of Michel Legrand’s “Windmills of Your Mind” is on a soundtrack for good reason rather than for its (reported) soothing effects. Tom’s journey from the sudden termination of a linear relationship, with beginning, middle, and end, into a morass of continuously conflicting feelings — the latter having also infected Francis—is best described by Eddy Marnay’s French lyrics, here badly translated into English:

Round like a circle in a spiral

Like a wheel within a wheel

Never ending or beginning

On an ever spinning reel…

And the world is like an apple

Whirling silently in space

Like the circles that you find

In the windmills of your mind.

The overlapping ambiguities contribute to the power of this thriller. Sara is the only character who can transform a chaotic world into a subjective, but consistent, organized system.

In a brilliant example of lateral meta-making, Tom adds precise scatological details to the complete rendition of his ode to Guillaume. I don’t think they are what Agathe was aiming for when she requested that her son’s “best friend” tell them more about Guillaume and Sara as a couple. Tom complies, but with a brilliant synthesis that is as uncompromising as possible between staying true to himself while still showing empathy to the vulnerable. He talks out loud about his own intimacies with Guillaume as if they were Sara’s indiscriminately repeated recollections. Sara loved to kiss his armpits; she commanded him, “Put your dick in my mouth.”

Assuming that Tom is disobeying his pact to keep the reality of the young men’s relationship from Agathe, fearful control-freak Francis is ready to pounce until his mother responds with a loud, strange laugh a few nanoseconds too late. She may be racing down the road toward psychosis, but for the moment she is tickled. This is the first we have seen her with anything close to a smile. “That Sara is quite the slut!” she blurts out, easing the mounting tension between the competing males. More than easing it: It diffuses it.

For the first time, Francis expresses some isomorph of feeling for Tom, going so far as to tell him, “I know you like me.” It’s true, and that is the Stockholm syndrome at work in matters of the heart, Patty Hearst-style. It doesn’t hurt that Tom finds that Francis looks and smells like Guillaume. Dolan — who has a costume-designer credit, and manages to make Tom look like a dandy no matter the situation — has Francis give himself a spritz of his brother’s perfume, even though Francis had said how much he dislikes it, in case anyone misses the point.

Tom goes further than revealing his and Guillaume’s carnal history. In order to chide the Longchamps family for somehow allowing his lover to die and for judging the relationship he views, as it happens, through rose-colored glasses, and to beat himself up at the same time, he mixes up pronouns in his exposition, as if it is the repetition of an overheard phone conversation.

“You’re worthless. You couldn’t stop him from dying. You’re nothing….For his love was between two people: no friends, no family.”

The Stockholm syndrome once again rears its ugly head. It becomes a dialectic. It starts to look as if Francis had written the monolog for Tom.

I hate myself. I’d do anything to set things straight.

Cinematographer Andre Turpin does a marvelous job of plugging some of the locations’ allure without losing the overriding sense of alienation. The single problem with the photography is proportion: Even more handsome as he ages than he was a mere five years ago when I Killed My Mother put him on the festival map, Dolan is far too compelling a presence to be in almost every single frame. (He can also perform: He was a child actor.) The narrative pays a price for so much overwhelming narcissism; it distracts from the whole. The co-written script worked out, but the direction required another set of eyes and ears — like an astute producer as forceful an influence as Francis — but more balanced!

The brilliant score by Gabriel Yared so enhances the thriller quality of this low-budget film that the soundtrack could pass for a luscious Hitchcock production (of what Dolan calls a film of the romantic-panic genre). Something about the way Yared combines strings and piano, the manner in which he amplifies or lowers volume at particular moments, is visceral and cerebral in equal measure.

The end credits are accompanied by Rufus Wainwright’s sober “Going to a Town.” The soft, melancholic melody is on target for an ambiguous nocturnal scene in which the lights of downtown Montreal glow as abstract shapes. The physical and emotional trauma he has gone through over the past few days finally behind him, Tom merely sits in his car and appears to reflect on all that has transpired.

Tell me, do you really think you go to hell for having loved?…

I’m so tired of America…

Making my own way home, ain’t gonna be alone

I’ve got a life to lead, America…

And that’s all I need.

Like Dolan’s work, the lyrics are gorgeous, political, critical — and ultimately hopeful.