Back to selection

Back to selection

Respect and Integrity in 27 Days: Peter Sollett Discusses Freeheld at Bloomberg/IFP’s “Business of Entertainment” Breakfast

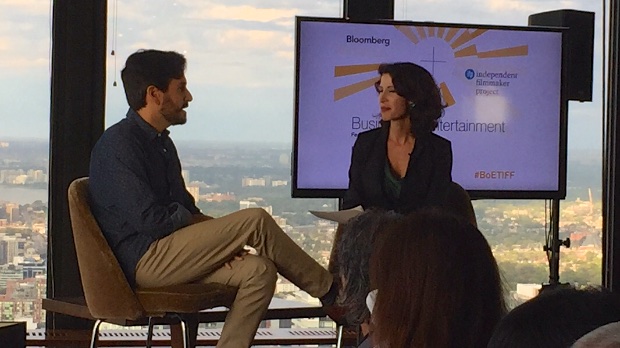

Peter Sollett and Katherine Oliver at the "Business of Entertainment" breakfast

Peter Sollett and Katherine Oliver at the "Business of Entertainment" breakfast “Finding a way to produce this movie in 27 days was a riddle we were always solving,” recalled director Peter Sollett. “And doing it in a way that had integrity, the kind that Laurel and Stacie had, was a challenge and a mission statement.”

Sollett was speaking at a Bloomberg/IFP “Business of Entertainment” breakfast, hosted by IFP board member and Bloomberg principal, Katherine Oliver, high above downtown Toronto and overlooking Lake Ontario on the eve of the world premiere of his latest feature, Freeheld, at TIFF. Oliver was introduced by IFP and Made in New York Media Center Executive Director Joana Vicente. [Editor’s note: IFP is the publisher of Filmmaker.]

Freeheld stars Julianne Moore playing Ocean County, NJ cop Laurel Hester, who battles terminal cancer and the police department for refusing to transfer her pension benefits to her female lover and partner. Ellen Page plays that woman, Stacie Andree. The film is based on a true story that was captured in the 2008 Oscar-winning short documentary, Freeheld, directed by Cynthia Wade.

Sollett (Raising Victor Vargas and Nick and Norah’s Infinite Playlist) replaced Catherine Hardwicke soon after the $7-million budget was raised in mid-2012. When he received the script from screenwriter Ron Nyswaner (who wrote another courtroom drama championing gay rights, Philadelphia) Sollett felt he had come full circle. “Ron is somebody I met years ago,” explained Sollett. “He was an advisor at a workshop at Sundance Writers Lab where I was developing the first script I wrote for my film, Raising Victor Vargas.”

To stay under budget and remain within the tight 27-day shoot schedule, Sollett limited his shooting ratio to four shots, read and dissected the script with his cast (which includes Steve Carell and Michael Shannon as Hester’s gay lawyer and supportive police partner, respectively), strictly followed his shot lists, and planned carefully with D.P. Maryse Alberti to make his days.

A hurdle arose when a few locations that objected to the subject matter, such as a Catholic boys’ school in New Rochelle, New York, changed their minds and refused permission to the crew. In the end, really, New York substituted for New Jersey due to the state’s generous tax incentives.

Another pressure, but also inspiration, came from the real-life Stacie Andree advising Sollett and the actors. Her constant presence, said Sollett, “served as a reminder how important it was to get the facts of the story right and to present those characters with respect and integrity.”

Andree didn’t challenge the actors but in fact was “very open with what Julianne and Ellen were doing, and she was very moved,” Sollett recalled. In fact, being on set was at times challenging for Andree. “There’s a moment where Julianne is wheeled into a scene, and she’s very ill, and that was tough for Stacey to see that,” said Sollett. “You can imagine how emotional it was for Stacie seeing somebody playing her life and experiencing all of that again,” Sollett recalled. (Andree appears in one of the final courtroom scenes where she’s sitting right behind Ellen Page, her on-screen character.)

It was trickier to stickhandle Steven Goldstein, Hester’s flamboyant lawyer. “His techinique,” noted Sollett, “is really to provoke, disrupt, amuse — really he’ll take it anywhere to get what he wants. He’s very successful that way.” On set, the real Goldstein kept urging Steve Carell to push his charaterization further, much further, but Sollett recalled his actor’s reaction. “At a certain point, Carrell said, ‘[If we do that] we’re going to make this movie about Goldstein and not about Hester and Stacie Andree.’ And he reeled it back a little to keep it consistent in tone.”

Carell provides a little comic relief in a serious film, but he remained faithfull to the truth of his character. In fact, stressed Sollett, “The agenda of the cast and crew became representing the experiences of the real-life people accurately and doing it in the most interesting way possible.”

As host Oliver pointed out, Freeheld isn’t a big-budget, comic-book blockbuster, but a social issue drama, which Sollett feels is lacking now in America. “The nature of mainstream film in this country right now is a little bit conservative. I think experimentation isn’t necessarily rewarded.”

The message he wants to get across in Freeheld is simple yet controversal: “We’re all entitled to equal rights in spite of who we love.”