Back to selection

Back to selection

NYFF Critics’ Notebook: De Palma

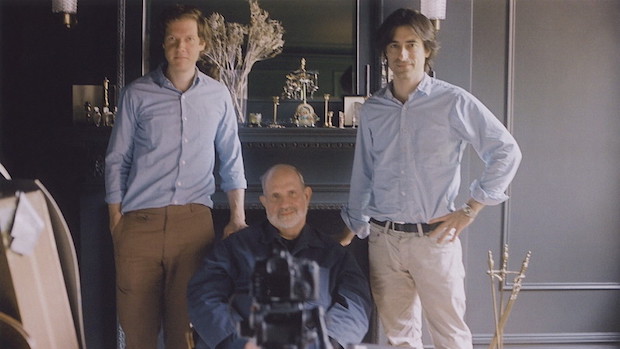

Jake Paltrow, Brian De Palma and Noah Baumbach (this image is not in the film)

Jake Paltrow, Brian De Palma and Noah Baumbach (this image is not in the film) Noah Baumbach and Jake Paltrow’s De Palma is a fans-only interview session with the director. Straightforward, even staid in its construction, it consists almost entirely of two shots of a seated De Palma — one in medium close-up, the other presumably punched-in in post — and appositely illustrative clips and stills. The film currently only has two credits: the opening all-caps title “DE PALMA” scrolling left to right in lurid red, and a closing copyright credit (hard-working editors will, presumably, be thanked at a later date). Interlocutors Baumbach and Paltrow are never heard; according to this useful interview, they never even considered miking themselves.

The movie spends zero time arguing for the merits of De Palma’s films (or synopsizing them; this is not for beginners), which are taken as a given. As a fan, I’m all for it: De Palma’s elaborately constructed, thinly characterized exercises in glossy tracking shots and cruel, not quite cheap thrills are inherently cultish by nature of their general indifference towards ideas of what “good narrative practices” look like, and at this particular moment that cult seems fairly small. If you accept the idea that Brian De Palma is worthy of serious consideration and respect, the documentary will underline that he can articulate exactly what he’s up to. The director/often writer observes that he constructs the plot first, then fills in the characters, and that his favorite part of the movie is the buildup so sensuously prolongs in those endless glides and zooms (“In my movies, the run-up goes on forever”).

Baumbach and Paltrow don’t remove themselves entirely; when De Palma describes mid-’70s United Artists as a “classy” studio appalled by Carrie, a quick montage of the studio’s offerings includes a blatantly risible shot of dancing Russian peasants from Fiddler on the Roof, quickly/snidely/accurately making the case for De Palma’s obvious aesthetic superiority to his now-dusty prestige peers. Clearly more comfortable talking to fellow directors than he might be otherwise, De Palma offers up details about each film’s budget and how each affected his up-and-down career trajectory. The recurring emphasis is on the unpredictability of professional success, and each film’s repercussions for what De Palma could subsequently raise money for, reminding us that being a director is as much a full-time administrative hassle as it is a creative pursuit.

Film writers (I’ve been guilty of this) often leap to conclusions about why directors take on assignments or make aesthetic choices; this practical, peer-to-peer chat is a useful reminder that keeping up with business movie journalism and thinking about production logistics is as useful a tool to understanding a body of work as any. The movie also helps slightly revise the now-beyond-ossified canon of the Easy Riders and Raging Bulls who either changed the world or crashed and burned, reminding us that extremes (the Lucas vs. Cimino binary) are overstating the case, that middle ground existed, and that past failures and successes only count for so many years. De Palma and George Lucas were both legitimately part of the underground before channelling their ambitions into more financable form. Another close friend was Steven Spielberg (seen calling De Palma from his early-adopter car phone in a Super 8 home movie from in 1976, a nice get); given different proclivities, it could’ve been an equally lucrative career.

De Palma largely sticks to the numbers and production hassles, which is smart: really, what could he contribute to yet another formulation of Voyeurism And You, The Implicated Viewer? The film is edited at a lucid gallop, which makes it easier to connect the dots between De Palma’s recurring visual motifs as expressed and developed over time. E.g., you can see his aesthetic in early motion at MoMA in his 1965 op-art exhibition doc The Responsive Eye, in elegant but comparatively shaky handheld, and how he revisited his approach to the space with gliding Steadicam in Dressed To Kill. The doc is implicitly a work of critical advocacy for a currently somewhat unfashionable director, though it’s realistically for the already converted. It’s illuminating and edifying, if not precisely revelatory: the big Rosebud anecdote/thematic decoder key (about De Palma filming his cheating father’s partner entering his office from across the street, then charging in confront dad) has been told many times before. But it’s useful to be reminded how directors can think of themselves and their work: as conscious artists, of course, but also as endlessly badgered managers and worker drones, depending on where they are in their career.