Back to selection

Back to selection

“I Don’t Want to Make Audiovisual Historical Aids”: Kent Jones on Hitchcock/Truffaut

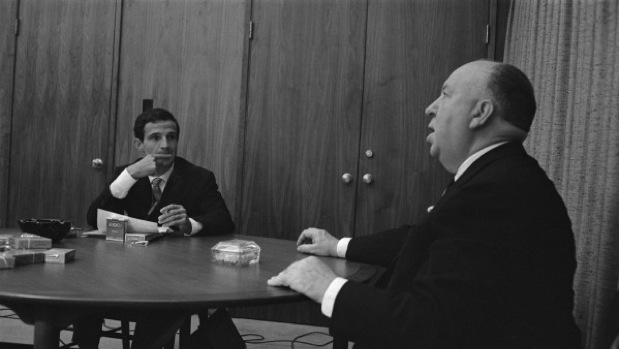

Hitchcock/Truffaut (though not in that order in this picture)

Hitchcock/Truffaut (though not in that order in this picture) The formal title of Hitchcock/Truffaut (alternately Hitchcock and The Cinema According to Alfred Hitchcock) is a vexed question mooted by its famous title design: Hitchcock’s name on one side, François Truffaut’s on the other. First published in 1966 and revised before Truffaut’s death, it’s one of the most commonly name-checked starter texts for anyone looking to learn more about film. In a series of extensive, probing and relatively unguarded conversations, Truffaut guides Hitchcock through his work film-by-film. Illustrated by numerous stills (including one- and two-page layouts showing every shot choice from particularly famous/intense sequences, breaking them down in a lucid, teachable way), the book allows a director in total command of both his technical and artistic craft to fully explicate himself.

Best known as a critic and programmer, Kent Jones has also directed four documentaries: two with Martin Scorsese (Lady by the Sea: The Statue of Liberty, A Letter to Elia), two by himself. His Hitchcock/Truffaut is part primer on the book and its making, part overview of the scope of Truffaut and Hitchcock’s careers, and — most interestingly — an opportunity for a murderer’s row of directors to speak not just about their fondness for the book, but their deep reads on its subject’s films. Richard Linklater, Wes Anderson, Arnaud Desplechin, Olivier Assayas, Peter Bogdanovich, James Gray, Kiyoshi Kurosawa, Martin Scorsese, Paul Schrader and David Fincher are all onhand to speak, delving and dilating (like the book) most extensively on the mid-/late-career touchstones of Vertigo, Psycho and The Birds. (Another director is narrator Bob Balaban, whose presence is a deliberate connection to the text; Balaban acted with Truffaut in Close Encounters of the Third Kind.) My first question for Jones was very long, and barely even a question, but I couldn’t figure out a way to work it back into this introduction.

Filmmaker: I hadn’t read the book until last week — I knew it was one of things I was supposed to read, but your film prompted me to finally get it done. While reading it, I thought its appeal for all these disparate directors might be the idea of a total director. Hitchcock sounds almost exactly like Fincher when he says early in the book that he learned how to do everything so that no one could tell him it couldn’t be done. I’m sure the guy who made, for example, San Andreas knows how to manage a post-production pipeline, but that’s all he knows. On the other hand, somebody like Mizoguchi is obviously an auteur, but he didn’t care where the camera went — he left that up to the DP. So probably the biggest draw is that Hitchcock can speak so articulately to the technical side of things — to the extent of asking, unprompted, “Do you know how we did that shot?” — but at the same time is able to speak about what that image means. I would think that for filmmakers, the idea of being able to articulate both sides of that that would be very important, because the idea of making an image is not necessarily intuitive.

Jones: I think that their relationship to the book is the same as their relationship to film, really. It’s a formative object, in the sense that as a book, it functions like a film. It’s edited by Truffaut for a flow that feels like a film, not informationally. However, it does, as Fincher says, cover very basic things about how you make a movie. My sense is, that for somebody like him — who’s the one that has the kind of connection with the book that I did, meaning we’re about the same age, he pored over it like I did, reading certain sections and looking at those photo montages over and over again — it’s not an intellectual connection. It’s about the relationship between the two of them. Yes, one of them was a critic, but he isn’t any longer and he’s an international superstar already. There’s a mission; the mission is obvious, but it is a one-to-one thing. It’s not a discussion of Truffaut’s work at all. So, I think it’s absorbed the same way a film is absorbed. Whether or not, after the fact, it illuminates the question that you’re asking, I’m not sure. Probably it does.

Filmmaker: One of the things I found when I started doing this job and learning a lot more about production logistics was that it inspired me to ask filmmakers a lot more about production logistics — which often, during the interview process, they’re not. So part of me feels like only filmmakers should interview other filmmakers. That’s really extreme, but there’s often a lack of comprehension displayed by interviewers about how films are made. It occurred to me that as instructive as this book might be for filmmakers, it might be even more instructive for journalists.

Jones: Agreed. That’s an interesting problem in film culture. In a lot of discussions of film, there’s a preservation of film culture first. I remember when I used to chime in a lot on Dave Kehr’s website, somebody at one point was saying “Gee, this is a great chronicle of the history of auteurism.” I was thinking, “The history of auteurism? Why is that interesting?” I guess it is, but it’s not really that interesting ultimately. Auteurism is interesting as something that shifted the focus of the terms in which we think about film criticism — and that’s for the best, I think. But it is true that there’s a lack of comprehension of very basic things about filmmaking. It’s an easy adjustment. You’re saying that you bring up the contingencies of production and the particulars of how they were made. You’re probably talking to people about what cameras they were using and the kinds of choices they’re making. I don’t think that that’s a huge adjustment, or that it should be. And yet, it has been for a long time, and that’s an odd thing. I know a lot of people who would call themselves “cinephiles” who have a certain amount of scorn for the book.

Filmmaker: Why is that?

Jones: Well, you know. There’s the Truffaut/Godard thing.

Filmmaker: Sure, if you think that’s a meaningful polarity.

Jones: Some people do, you know that. It’s the Lennon/McCartney thing. Truffaut is the ambitious young guy who married the daughter of the producer and wormed his way into the film industry and didn’t care about everybody else; Godard is the one who seems to be an asshole but he’s secretly put-upon and he loves cinema more, etc. etc. But — ultimately, I agree. People should be reading the book. [laughs]

Filmmaker: In the opening narration, you name it as one of the few essential books about film. What are the other ones? I also noticed while reading up on this that in David Bordwell’s post in the film, he points out that, yes, there was Cahiers in English and Andrew Sarris’ interview collection, but the latter is assembled from pre-existing interviews. Do you think this is a year zero reset?

Jones: I think so, in the sense that interviews between filmmakers are very different than interviews between critic and filmmaker. I think emotionally, it makes a difference. For Hitchcock, he can correct this impression about himself. That’s different from Andrew Sarris or Philip French or Charles Thomas Samuels or somebody like that.

Indispensable film books are hard to come by. Yes, Negative Space by Manny Farber is an indispensable film book, in the sense that that is somebody who somehow found his way into some kind of understanding of how films were made. He did it through a different kind of process; he went through the back door. But in some way, even though he sidelines narrative more than he should have — because he was too worried about being cool, I think, and always being in a vanguard position — and even though Negative Space is a little skewed in the direction of the moment it was published and the selections that he made, I do think he found a way of talking about films quite apart [from others]. Other books? I don’t know. Andrew’s book was a great thing at the time, as a book.

Filmmaker: It’s an agenda which stops in 1967.

Jones: And the Cahiers book is great, but that’s something else. It’s a whole other thing. It’s an artistic manifesto.

Filmmaker: You have a very quick excerpt from a Godard review in the film. Is this your oblique way of getting him in there? Because the film is kind of a primer, and then there are these little contextual details that, if you expanded upon them, the film would be eight and a half hours long.

Jones: I thought about different things for a while. There was a little section about Chabrol in there, but that seemed to stick out like a sore thumb. When Truffaut was doing the book, he was responding to the American perception of Hitchcock, but he was also responding to what he saw as the overly abstract tendency in Cahiers du Cinéma criticism — i.e., Godard. I mean, I suppose you could say Rohmer too, Rivette too. Godard’s piece about The Wrong Man is a remarkable piece of writing and criticism, but it’s removed from the actual conditions of filmmaking. It’s taking Hitchcock away from Hollywood and putting him on an Olympian plane, alongside Mozart and Homer and whoever. Getting into that, that’s a whole other subject. But I did want to situate people in that world of Cahiers, and getting [Godard’s] voice in there was a good idea as far as me acknowledging him.

Filmmaker: Before you got started, did you listen to all of the available audio?

Jones: Yeah.

Filmmaker: Were there any easter eggs in there for you? You talk a little in the narration about how Hitchcock’s drollery is more evident.

Jones: He’s very funny, he’s very spontaneous. He spoke French — badly, but he spoke it. Truffaut doesn’t speak a word of English. 27 hours, there’s a lot of stuff in there. You could’ve made 20 different movies. I don’t know, I suppose I’m really intrigued by his unwillingness to argue. I think he found it really unseemly.

Filmmaker: It’s often said that Hitchcock was very eager to go along with the interviewer and that his story could change from one to the next.

Jones: I think that’s true of almost everyone from that generation. They followed the lead. In Hitchcock’s case, most of the interviews I know with him are of the “When I was three years old I was locked up in the police station” variety, and “actors are cattle,” and “I received a letter from a woman who said that she stopped taking showers after Psycho.” That kind of stuff. With Truffaut, because he was a filmmaker, it was different. But when he’s asked about dreams, his voice gets very, very quiet. [lowers and slows voice] “Daydreams are probably me within myself,” that’s a very short, clipped statement that’s meant to shut down the conversation. At the same time, it’s a fascinating choice of words, “me within myself.” Or when he’s talking about Vertigo — [slowly] “It’s from the point of view of an emotional man” — then, when he’s asked if he liked it, [brightly] “Yes, I enjoyed it.” Then he gets sparkly and into the Vera Miles narrative. That kind of game-playing, working around and through emotions, I find really interesting.

Filmmaker: You keep saying someone asked you to make this. Who asked you?

Jones: Charles Cohen, of Cohen Media Group, but I jumped at it. I didn’t say, “Give me five seconds to think about it.” He called me two years ago. I had to talk to the European co-producers, they signed on with me. I was in Mexico at a film festival in February 2014 and started going through the book again. Then I got the tapes. In May 2014, I shot Olivier in Paris. I guess Marty and Rick were the last ones. The interviews were a little bit at a time. I went to LA in August to do James Gray and Fincher and Peter Bogdanovich. Abi Sakamoto did Kiyoshi in Tokyo, I wasn’t there for that one. I thought Kiyoshi was going to be in Paris, but it didn’t work. But it was great, because Abi’s a close friend, and she did a great job. We were editing as we went along, and we built it from the middle out. I wanted to cover the interview and not think about a pre-determined structure of the historical armature. I wanted to build it from where it felt like there was real narrative, intellectual and emotional energy between the two of them, and then build it out and put my interviews in.

Filmmaker: Do you have a rulebook for how to conduct the interviews?

Jones: No. What I did was find questions based on areas of the interviews, plus conversations I’d had with these guys. Arnaud and I have always talked a lot about Hitchcock. We talked about Hitchcock when we were writing Jimmy P. Marty and I have spent years talking about Hitchcock. One thing I don’t do is, “Can you say that again and include the name of the film?” You can always tell that it’s being redone, you can hear it and you can see it. So it creates more of a problem for the editor, but I don’t want to sacrifice the spontaneity.

Filmmaker: There’s a decision made not to label a lot of the films. Is that a graphic design decision?

Jones: No. I don’t want to make audiovisual historical aids. I want people to confront a clip head-on, rather than “Oh, there’s a clip from Rich and Strange.” In other words, just to confront the matter of it. At first, the producers were a little bit dubious about it, but then they got the point.

Filmmaker: The pool of interviewees are drawn from your work as a programmer, and it seems like you’ve curated a group of filmmakers that you’ve found to be among the most important working now, and then they’re drawn towards this common center of gravity. There are links between them — Desplechin likes Dazed and Confused, for example, but that’s not necessarily obvious per se. Is that your sneaky canon-building on the side?

Jones: Not at all. What I wanted were people who I knew were going to respond, as opposed to, “Alfred Hitchcock is one of the greatest artists in the history of cinema.” I’m not interested in that. I got stuck with that in one movie that I made, once, and even he had a couple of things to say. I want people who can think in that situation on-camera — talk about the basics of film history, making movies, that kind of thing. I could have made a different movie out of virtually every word out of Fincher’s mouth. Marty, too. James is a whole other reality, he could talk for ten hours. They’re almost like different planets, some of them.

Filmmaker: Why is it important that somebody else narrate the film and not you?

Jones: I have a self-consciousness about my voice, and that has to do with the fact that my dad was a DJ who had a really sonorous voice. He was a DJ who started in the ’40s. He was known as the “Voice of the Berkshires.” To me, my voice is sort of neither here nor there, but I’m sure everybody thinks that. There were other thoughts too: maybe we want Meryl Streep? That kind of thing doesn’t interest me. I wanted somebody who was a filmmaker with a connection to the work. When I originally designed the film, I didn’t want narration at all, but it did need nuts and bolts.

Filmmaker: Do you feel like the book has fallen out of common circulation?

Jones: No. God knows how many printings it’s had.

Filmmaker: It’s just that there’s a fair number of starter texts — this, What is Cinema?, maybe P. Adams Sitney, all of which date back a fair way, and I wonder to what extent they’re still taught and introduced.

Jones: I have no idea. Academia and I, we’re like ships passing in the night. It’s hard for me to imagine. I was giving a talk at a class that a friend of mine taught at NYU, asking “How many people here have seen a silent film?” One guy raised his hand and said “I’ve seen one, once, on YouTube. I saw 20 minutes of The Big Parade.” That’s just the way things are. One can rail against whatever, but that’s where things are at.

I did learn a while ago that there is no such thing as “Mission accomplished.” Things happen incrementally. We can speak about the director now — when people talk about films now, they talk about the director, in general. When they’re reviewing movies, they say “Michael Bay’s Transformers 4,” even if they don’t think of themselves as auteurists. That’s different from when I was young. What they have to say about the film doesn’t amount to anything terribly different from the Hollywood crap I read when I was young, but the way that they’re framing it is different. Film culture was different. People were interested in films who were not into labeling themselves as “cinephiles.” They were interested in films as cultural events in a way that they just aren’t now. You have specialized audiences now, smaller audiences. I don’t know how film is taught, and I’m trying to decide if I care.

Filmmaker: I’m legally obligated to ask you about the lack of female filmmakers interviewed. I’d heard that Jane Campion dropped out.

Jones: Nobody dropped out. Jane said “Thank you, I’m very busy, I have absolutely nothing to say about Alfred Hitchcock.” I asked someone else who was very cagy and said “That’s interesting and I love Hitchcock, but I’m very shy.” I wanted somebody else was in pre-production, and there was another filmmaker who was an area of conflict with the producers. There weren’t many, but that was one. For me, it’s not a question of having women in the film, but of having directors who I know are going to respond and have something to say about Hitchcock, or who I sense are going to have something interesting to say about Hitchcock. That whole question of having the token woman, or having a woman because she’s a woman, to me is inadmissible. That’s a question that goes beyond cinema, the fact that there aren’t that many women filmmakers.

This kind of rhetoric is very convenient, it’s media-friendly, it’s extremely punitive, and it’s not really helpful, in terms of the ultimate question. Helen Mirren was asked a question by Terri Gross: “You talk a lot about the representation of women in the film industry.” She said “No, I really don’t. People like you say that I do. What I say, always, is that it’s not a matter of having women directors and producers. What it really is is a matter of the greater society.” As soon as there are more women in all jobs, then there will be more women directors, but don’t go think that operating through social engineering and quota systems is going to change much. It’s a question that’s so deep-rooted in terms of the burden of subjugation that women still carry with them, and that men still carry with them — the burden of the woman’s subjugation, even though they talk another talk — that it’s too important to be settled by having a quota system, or making it a matter of “Oh, I’m not going to make a documentary unless there’s a woman in it.” That’s a trivialization.