Back to selection

Back to selection

Time and Tempo

by Nicholas Rombes

Underground Desires

Eraserhead

Eraserhead Probably like a lot of people, I loved underground cinema before I knew there was a name for it. My first encounter with the term was in a book that only used the word once, and not in relation to a certain category of films but a specific film: Underground U.S.A. (1980) directed by Eric Mitchell, who had acted in several Amos Poe films, most notably The Foreigner (1978). The book was Midnight Movies (1983) by J. Hoberman and Jonathan Rosenbaum, whose sharp, knife-like prose and generous, half- and full-page black-and-white frame enlargements worked to construct — if this is possible — a film logic of their own.

I was reminded of that book recently by another, similar one: Underground U.S.A. Filmmaking Beyond the Hollywood Canon (complete with a blurb by Jim Jarmusch on the front), and published by Wallflower Press in London in 2002. A short digression: the book was co-edited by Steven Jay Schneider, who at the time was a graduate student in philosophy at Harvard and in cinema studies at New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts. It was through this book that I learned of him and contacted him, which lead, eventually, to him commissioning my book New Punk Cinema for Edinburgh University Press. He, like many of us in film studies at the time, was restless in academia and secretly wanted to make the films we wrote about. In Schneider’s case, he moved to Los Angeles where he served as producer on the Paranormal films, helping to usher in a new structuralism, which, Trojan horse-like, used the generic body of the lowly horror genre to smuggle in techniques more commonly associated with experimental and avant-garde traditions.

Has the term — and the very concept of — an “underground” cinema become purely historical, something that cannot exist in an era when the temporal gap between an underground movement and its inevitable publicity in the mainstream has all but collapsed? Are underground films possible in a real-time digital culture? Or, can the term be re-appropriated to mean something different in the digital era, in the same way that terms like cut, scroll and page view have been repurposed from analog technologies?

In an era when the cultural radar picks up on and disseminates artistic movements before they have had time to develop, I think what still exists is the affective power of such movements — a feeling of “undergroundness,” even if the term itself has become dissolute. Annalee Newitz has written that the term underground “suggests that despite the usual blizzard of politically cowardly and culturally unremarkable films, there is a hidden cache of daring, revolutionary and independently created movies which lurk literally just under our feet, if we would only look.” Her essay — published in 1999 — considers American Beauty as one such film, a film that went on to win five Academy Awards, including Best Picture. The ironies are obvious, and I think Newitz’s selection of American Beauty as an underground film gets at the heart of things, for in 1999 there was a feeling that certain films — including The Blair Witch Project, Fight Club, Election, Three Kings, julien donkey-boy and Being John Malkovich — captured a feeling of sly, subversive danger that had been absent for a while in the era of post-Reagan, neo-liberal American cinema.

There is something about the structure of these films — we might call it an affective structure — that leads to a feeling that the films have come from the deeper, darker corners of the shiny happy culture. From a materialist/production point of view, they are not underground at all (with the possible exception of julien donkey-boy), as they are all made by professional filmmakers working within a firmly established finance system. Because oppositional categories such as art/commerce, mainstream/avant-garde, etc. are, the closer you look, artificial constructions, these and other films generate subversive, even anarchic, feelings and moods that belie their big budgets and stars. And yet, 1999 feels like light years away, partly because 9/11 came down as a before-and-after traumatic event that created a far more expansive temporal gap than mere calendar years would suggest, and also because the Web fully came into its own as a real-time machine that, through its readily accessible archiving features, shatters boundaries between past and present. (The past is always the ever-ready present on the Internet, just as the present is always already doomed to the past.)

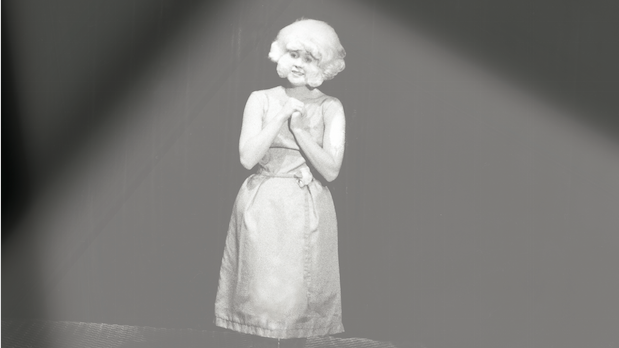

I am of the generation marked by the sign of the analog, and thus prone to nostalgia — even if I deny it, which I often do — for “those times” (the 1970s, when I was a teenager) when it was more difficult to discover and get hold of the obscure source materials that seized my imagination. Growing up in the rural Midwest made the process even more challenging and fun; you practically had to be detective-like to hunt down all the rumors about punk, no-wave, so-called midnight movies and other cultural expressions that existed primarily as slim rumors. Then, as now, the underground existed more as idea than as a place or object. The books, magazines and VHS tapes that eventually confirmed the actual existence of such objects only added, in pieces and fragments, to the aura of mystery. Eraserhead, for instance, was released on VHS in 1982, making it possible for people like me in Ohio to actually get my hands on the bloody thing (we rented it from our local U-Haul dealer, but that’s another story) after so many years of hearing about it and pouring over the few images of Henry that I had.

Perhaps underground cinema always was more of an idea than a place. An idea activated by our repressed desires: visions not only of alternative ways of being, but alternative ways of making movies. The names and categories come and go, but that feeling you get remains — that feeling, when the screen lights up, that this is it, this is the something I didn’t know I was longing for until it appeared.