Back to selection

Back to selection

True Crit

Weekly film reviews. by Howard Feinstein

Spotlight: Gabriel Mascaro’s Neon Bull

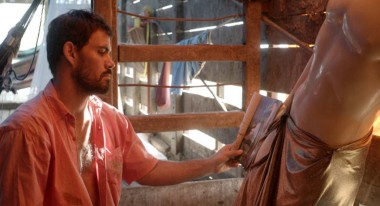

Samya de Lavor, Juliano Cazare in Neon Bull

Samya de Lavor, Juliano Cazare in Neon Bull “Sand that tail!”

Iremar (rising star Juliano Cazare), a musky, melancholy young vaquero, or bull handler, is shouting at Ze (Carlos Pessoa), his flabby, more light-spirited compadre on the service crew at a vaquejada, a specialized rodeo popular in relatively impoverished northeastern Brazil. The crowd, comprised of local rural peasants whose taste and practice have evolved little beyond the age-old ways, gets all worked up watching two horsemen attempt to bring down by the tail an ornery animal bucking in a state only a little more frenzied than the one fans have entered. The game may be simple, but to outsiders it’s simply weird.

The men who manage the bulls and mount the horses — indeed, the competition itself — are among the diminishing remnants of a homogeneous macho culture. This is a world, and a film, in which the body, whether human, animal, male, female, or something from the in-between gaps, figures more prominently than usual, even if it is as far off the beaten track as the surprise-laden narrative itself.

Bodies and machines serve as the film’s principal motifs. That the body is a well-oiled machine is duly noted, but that subject alone would demand an entire essay. Iremar’s lust for the latest in modern factory technology may well be a function of his increasing frustration with his undependable sewing machine, so antiquated that it’s nearing the status of a relic.

On the surface, he fits the stereotype of a masculine cowboy. Though this beefy male engages in heavy labor, he does not conform to the conventional definition of a man. There is an overriding sensuality about him. He tells the passive Ze to clear the left-over tails of their bestial odor and strip them of their natural texture so that he can convert them into decorative elements for the headpiece of a female stripper’s outfit — a “mask with a mane,” he calls it. For most of the area’s residents, this is girly stuff.

In his precious spare time, Iremar sews costumes for sexy, fake-blonde Galega (Maeve Jinkings), a fellow member of an itinerant rodeo family and single mom to precocious pre-teen daughter Caca (Aline Santana), the object of his bottled-up affection. (The collection of unrelated people sharing their day-to-day lives is one example of alternatives that have sprung up at a time of greater mobility, harsh economics, and the collapse of the nuclear unit.)

Brazilian director Gabriel Mascaro (August Winds) — whose background in docs such as High-Rise (interviews with maids of the wealthy) and knack for penetrating the hidden world of the marginalized poor he puts to effective use in Neon Bull — undermines the premises of the generally accepted labels masculine and feminine. He revises and expands them. While Iremar engages in pursuits the larger society deems feminine, Galega labors in a traditionally masculine vein. She is mechanic for the clan’s enormous truck, as well as guard and dispenser of the irreplaceable contents of their invaluable toolbox.

When necessary for the validation of his positions on gender, Mascaro sets up situations that have certain expectations attached, then proceeds to refute them. Take Junior (Vinicius de Oliveira), the twentysomething ranch hand who replaces Ze. He obsessively blow dries and irons his beautiful, long, raven-colored hair. His androgynous countenance smacks of effeminacy, perhaps homosexuality. However, he has no problem with physically demanding chores, and he most certainly goes for the gals.

All the world’s a stage in the director’s catalog of behavior. Many of the film’s segments fall under the general umbrella of performance. Isomorphs of ingrained gender-based roles, in tandem with an eroticism that marks nearly every aspect of the characters’ daily lives, result in loaded tableaux that animate his ideological bent. Helping to structure the film is added value.

Anticipating the trope is the introduction of the bulls, which takes place along a narrow passageway, their individual access regulated by the rapid raising and lowering of a crude wooden gate by Iremar and Ze or Junior on opposite sides. Shot from a low angle, the symmetrical sequence resembles a succession of grand theatrical entrances. The gate can be seen as a rough-hewn curtain; the corridor, a primitive proscenium.

The spotlight falls on attractive strippers through colored filters not unlike the way that it marks a trainer and a champion mare walking primly in proscribed circles for judges at an auction, even though the latter is lit by diffuse illumination. It also targets Iremar furiously masturbating a top-ranked stud with an enormous erection in order to collect lucrative sperm to peddle for black-market mating.

(A surprise splash on Ze’s face, more stomach-turning than what happens to Cameron Diaz in There’s Something About Mary, provides an important comic element that keeps the two inept amateur crooks likable. So does an absurd series of George Burns-Gracie Allenish miscommunications. When, the day after the farcical mishap with the equinine jism, the violated horse’s wealthy owner arrives at the back of the truck where Ze sleeps soundly in his hammock, the latter assumes he has been found out and apprehended. He is wrong. After having seen his deft handling of a difficult horse, the patron is there to offer him a better paying job.)

Window and windshield make blocking impossible for Galega, when she inadvertently puts on a show in the driver’s seat of the truck’s cab. She gives herself what is meant to be a private bikini wax. (Mascaro never loses sight of the backstage, which for him is as significant as the completed spectacle. She is preparing for her public striptease. Neon Bull is a study in process.) Intensive highlighting takes place on a much bigger scale in the outdoor arena where the audience witnesses the main act, the one for which they’ve paid an entry fee: the conquest of a resisting bull.

Mascaro moves beyond the reinterpretation of the male/female dichotomy: He blurs the line between human and animal, literalizing the literary phrase la bete humaine. In one of the film’s multiple surreal inserts, extra powerful in what is otherwise an exercise in realism, a dreamily lit Galega dances suggestively onstage wearing the horse mask Iremar has designed to complement her gold lame g-string and a top unfit for covering more than nipples. In another scene, a half-naked cowboy and a horse participate in a succession of still lifes which simulate either an inter-species pas de deux or a lovemaking session: which is difficult to determine.

In several exteriors, the surprisingly graceful herded bulls fill the rear portion of the frame, or at least a large corner. It’s as if they are an ensemble of human movie stars. If that seems exaggerated, they are at a minimum fairly unobtrusive visual reminders of the foundation of the vaquejada and the ancillary culture that developed around it. Mascaro brings them to life with an assortment of set-ups and camera angles. They form the backdrop for the initial flirtation scene between Iremar and Geise (Samya de Lavor), a pregnant, door-to-door cologne-and-perfume salesperson already in her third trimester. Tellingly, the encounter, at the edge of a trough, succeeds. When their wordless moment of intimacy finally comes, it goes so far beyond the rituals of either humans or animals that it borders on transgression. It is an arguably pornographic illustration of an egalitarian ethic among species. The guiding principal is no longer just the blurring of distinctions: It is their near-total elimination.

Iremar may be the embodiment of the intersection of fantasy and realism that runs through the film, but Mascaro is the architect responsible for a credibly congealed polyaesthetic. Naturalism is manifest in what I term “agrarian romanticism.” Its components recall Constructivism, with its interlocking and opposing rectilinear shapes. You see his genius in the way he links these scenes with more stylized ones. His strategy of choice is the lateral pan, sometimes slow, at others a bit faster, but always with an uninterrupted flow that feels like Steadicam. With a few exceptions, the horizontal reigns.

The camera’s sideways movement seems to be guided by the crooked wooden slats, separated by enough empty space to maintain a substantial feeling of openness, in the endless fences that only minimally break up the vast terrain. Rare, but exceptionally beautiful, night shots compete with the bright daytime views, the latter yielding oddly appealing if banal multicolored objects like tasteless t-shirts hanging with the other wash, hammocks crisscrossing the exposed back of the truck, litter spread all over a large dump, and painted panels of scrap wood that form part of makeshift barriers and flimsy walls.

Together, the fences and pans form a majority of the frames favored by Mascaro (he deploys windows for most of the others). Framing devices help define characters and shed light on the motivation behind their actions. Just when you think that the whole is in danger of becoming dull, an unforeseen event energizes it. Seemingly out of nowhere, for example, Iremar appears inside an isolated mall ironically called Fashion City. Instead of checking out a department store’s products that have been carefully placed to attract the potential consumer, he wanders among tinted display mannequins, which, like fully revealing shots of women’s private parts, he requires for his singular designs. In the director’s vision of revamped gender roles, Iremar would never think of them merely as a means of getting off.

He finds a suitable plastic torso in the dump. It seems the right choice for a film extolling Mascaro’s unique, unpredictable, and off-beam artistic and intellectual worldview. Once Galega begrudgingly responds to his plea for a saw, Iremar cuts the surrogate body double in half. Within the narrative, the dismemberment makes sense. More significantly, the sudden shock yanks you out of any ennui-tinged state, conscious or not, you may have slipped into.