Back to selection

Back to selection

Seizure, Midnight Express and Platoon: An Excerpt from The Oliver Stone Experience

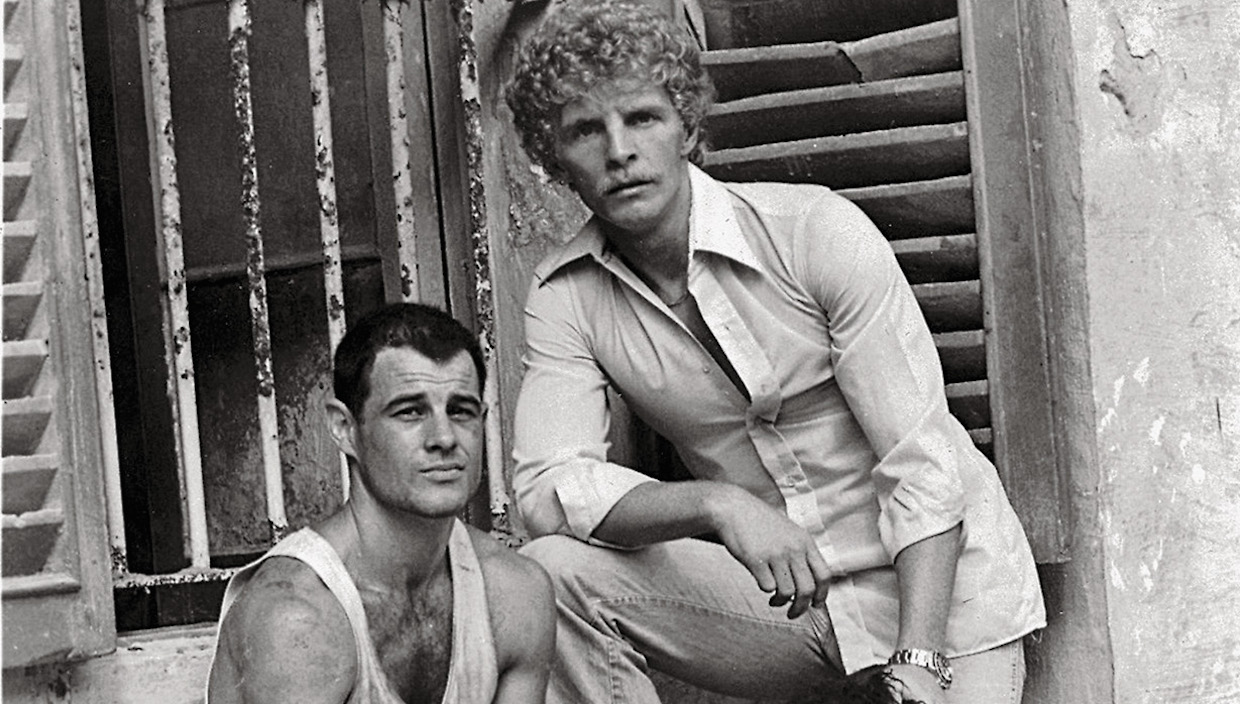

Publicity photo of the real William "Billy" Hayes with Brad Davis (left), from The Oliver Stone Experience (Abrams), courtesy of Oliver Stone and Ixtlan Productions

Publicity photo of the real William "Billy" Hayes with Brad Davis (left), from The Oliver Stone Experience (Abrams), courtesy of Oliver Stone and Ixtlan Productions [Editor’s note: the following interview is an excerpt from Matt Zoller Seitz’s The Oliver Stone Experience, out September 13 from Abrams Books. This excerpt from Seitz’s book-spanning interview with the director covers Stone’s life and career from his first feature, Seizure, through the production of Midnight Express and his initial, frustrated efforts to get Platoon made.]

I had a nightmare, and it became the basis of Seizure.

It came to you all in a dream?

Yeah, it did. It felt like a fever dream. A father ends up betraying his son, like a coward, and runs away and wakes up, and of course he thinks it’s all a dream, and it all starts again.

This script was originally titled Queen of Evil, after the ringleader of these three apparitions that sort of materialize out of nowhere and terrorize the writer’s family at his country house. Rounding out the trio is a black giant and a philosophical dwarf played by Hervé Villechaize[1]. The story is very much like something that Stephen King would write years later, about a horror writer whose creations come to life and cause harm to him and his family.

Seizure was a dream—Dead of Night, Cavalcanti, that’s closer to it—Alberto Cavalcanti[2]. In ’69, I’d taken a course in horror films at the New School for Social Research—before NYU, I think. Wonderful course.

I was also doing acting school. I was trying to do everything. I was with a Russian acting teacher for several months until I gave up, because I got stoned one night—I took LSD and went to class, and I’ll never forget, she said, That’s the greatest performance you’ve given yet! She studied with Stanislavsky, and had been talking this gibberish for months and I was trying to understand but couldn’t! Then I take LSD, do the fucking class, and she says: That’s it! Where have you been, Stone? What have you been doing? (Laughs) I get it! I gotta be on LSD to do this shit!

So yeah, I was always interested in writing and directing, but I was interested in acting, too. I was doing many, various things. At HB Studio—that was Uta Hagen’s[3] studio with her husband, the acting coach Herbert Berghof— I sat in on a couple of classes, but I didn’t have Hagen as a teacher. I had several other teachers there, though, including the great Bill Hickey[4]. I also did a modern dance class. I had the hots for the teacher.

Please tell me there are pictures of you in this modern dance class.

No.

(Seitz laughs.)

Anyway, I made Seizure after the sex film in late ’73, very cheaply and very wildly.

I gather that Seizure was not, to put it mildly, an easy shoot. I read something about the negative of the film being seized, and Hervé Villechaize threatening to kill you. There’s an article that quotes him saying, at one point, “I kill you, Stone! You no pay me, Stone, I kill you! I take a knife and stick it in your heart! Fuck off!”

(Stone laughs) Hervé was a character, yeah! It was my theory as a director that all the actors should live in the same house and we should share in this adventure together and shoot it in sequence.

How did that work out for you?

Disaster! (Laughs) Complete disaster! Everyone started to crack up. It’s very hard to shoot and live in the same house. You’ve done that, so I know that you know what that’s like!

I do! But at least when I shot a movie in my house, I didn’t have anyone trying to kill me with a machete.

That was not Hervé with the machete, by the way. Though Hervé did collect knives and threw them well. That was the special effects man, who was jealous of me because he thought I was screwing the lead actress, and he thought I was making the moves on her. He was so drunk, I don’t know what the hell I hired him for. He chased me.

(opens folder of documents) This is the press kit for Seizure. The official director biography, which I believe you wrote yourself, reads:

Seizure was filmed on location at Val-Morin in Quebec, on a remote country estate. It was shot in five weeks under a hectic schedule with very little money. The actors were American and English, and the crew for the most part French Canadian, the équipe headed by Roger Racine[5] of Montreal. Most of the shooting was done outside from night till dawn. There were many accidents, fights, injuries, and terrible food. The French dwarf in the film, Hervé Villechaize, disgusted, buried a chocolate cake in the face of producer Garrard Glenn. The special effects man broke all the windows in the house in a drunken rage. He was deeply in love with leading lady Martine Beswick, who bore no such feeling for him. Damages to the house were enormous. The producers cowered in fear from the wrath of the burly French Canadians, who finally threw them into an icy lake, hoping they would drown. Countless other humiliations occurred, and without further speech or specifying them, it should be pointed out that it was a miracle the film was finished at all.

(Laughs) Is that my quote?

You must have had to reach a certain threshold of frustration to make that your bio.

Yes. But it’s true. They threw the producers in the lake, and Hervé fell in a six-foot hole. Did I tell you about that?

No.

He was walking around one night, this place was weird, and he fell into a hole! All night he was like, Help me! Help me! (Laughs) You’re laughing!

You’re doing an impression of Tattoo from Fantasy Island[6] trapped in a hole! Yes, Oliver, I’m laughing!

Thank God my drunken assistant director went out and took a pee and heard him calling out to us. That was lucky, because Hervé would’ve died. It was hypothermia time. Hervé was a character.

But we couldn’t pay—checks were bouncing, it was a mess. Roger Racine [the director of photography] was an old-time French Canadian, and the crew hated him. He was pissed off at Jeffrey and Garrard, who were amateurs trying to make all ends meet with this money. The film was financed by a Toronto company, which went bankrupt three weeks before we started shooting. I went to their offices in Toronto, and they were really nice, but there was no furniture! They’d floated a lot of Canadian penny stocks in those days, which were notorious. And they went out of business.

So we were out to fucking lunch. We had lost half the budget. We had money from the States, which we’d found, but we only had half a budget.

So you went out and shot with only half a budget?

We made a deal with Harold Greenberg[7], who owned Bellevue-Pathe Lab, and he swallowed the whole film and took care of it to finish. Greenberg was a legend in French Canada, but tight with the money, taking a five-to-one write-off with his tax shelter deal.

Your Seizure files are an incredible record of financial distress: receipts, bills, collection notices, and letters saying, in effect, “Please, please, please send money.” It’s quite extraordinary.

Najwa helped me as much as she could with her connections. We got a wonderful man, Eddie, to put up twenty thousand dollars. But basically, checks bounced; the crew was not paid. It was a tough crew, very French Canadian, and they went on strike. That’s when they threw the producers in the lake. We got things done, and somehow we got through it. Racine was not paid, and he was pissed off. So I’m editing in Montreal—we’d moved the film there—and he didn’t get paid and he locked me out of the editing room. I somehow legally “seized” the film back under Canadian law. I accompanied the bailiff and police to Racine’s office to get the work print; he was livid. But we couldn’t locate the sound masters. But we smuggled the workprint out through the Michigan border in the back of a rented car we hadn’t paid for. We had to “re-dub” the whole picture, all from lip-syncing. Motherfucker! That motherfucker! (Laughs) And I lost some of the film! It was just a nightmare. Jeffrey had a warrant out for his arrest, and the Mounties were executing it, because of a rental car situation. We’d rented a lot of cars and we didn’t pay the bill. So basically, I remember driving the film in the back of my rented car through the border, with the film in the back, you see?

Getting that film across the border, that was scary. I think the negative was in the lab. But then we took the work print out. I got the work print back to the States, which was a big victory. The sound was still up there. Greenberg had the fucking negative, but I could keep working on the film in New York and hopefully find an investor-distributor. So we did all the sound work, the syncing, and then we took it to Sam Arkoff[8], and he said, Not interested. A lot of people passed.

But we got Cinerama[9]. At that point we’d reconciled a little bit with Greenberg, who had made the deal with Cinerama, a company that had done some classy horror films. It was run by a guy, Joe Sugar was his name. They put Seizure at the bottom of a double bill on Forty-second Street. I took my mother, who took several of her friends. She had champagne and we sat up in the balcony on Forty-second Street with a lot of strange people down on their luck to see the film, which was played too dark to see. The projector bulbs were pretty cheap in those days.

What did your mother think of the movie?

She was very proud of me, that kind of stuff.

But it was such a nightmare to get it out there. And it didn’t do my career any good, either. You liked some of the Guignol in the movie, right?

I did—although the movie’s very rough, as you say, and I think The Hand is ultimately a superior take on a similar story.

Vincent Canby, believe it or not, liked Seizure!

It was around this period, the early to mid-seventies, that you started to make a bit of headway as a screenwriter, yes?

Yeah. Fernando Ghia[10] read my treatment and brought me out to Hollywood, and it was really an eye-opener, because I’d written a first draft of a really good screenplay, “The Cover-Up,” that Robert Bolt[11] redlined with me over a two-to-three-week period at his office in Beverly Hills. Robert Bolt sat in a room with me for almost two weeks straight, just going over the script I’d written and tearing it apart, line by line practically. He rewrote so much of it that at the end of the day it was a brilliant script that really reads well, but it’s a lot of him. The script was sent to the best producers and directors. I learned a lot about the way he thought, and I saw the economy of scale and movement he used. He was originally a socialist schoolteacher, so it really was an education. I felt a real change in my writing, like I was getting better. It was my version of the Patty Hearst kidnapping[12]. That was an important step for me. And through Robert and Fernando, I got an agent.

So, about this unproduced screenplay, “The Cover-Up”: The main event in the story, the equivalent of the Patty Hearst kidnapping, turns out to have been a conspiracy. It turns out that two of the people involved in the kidnapping are revealed to have been undercover agents for the police.

There was some evidence to that effect.

It’s very Battle of Algiers![13] It reads as if the true purpose of the kidnapping is to incite enough rage against the counterculture to justify a government crackdown.

I got my information from a radical woman, a leftist living in New York. I didn’t follow up on it, but there was a tremendous identity issue about the black fellow who led that gang—

Donald “Cinque” DeFreeze.[14]

Yeah, she had told me about this guy. In this case, I don’t remember all the facts versus what we actually used in the script, because it kind of blurs.

But “The Cover-Up” didn’t get made. Broke me up, because it was at the time of Taxi Driver—Marty was succeeding, and I wanted to make a go at this business!

At that point, my marriage was falling apart. Although Najwa was very wonderful to me, and we had many good things together, it was not a marriage that was going to last. I was too much of a wild man. We broke up, and I moved into a friend’s apartment. At that point, summer of ’76, I said, I’m going to make it or break it: I’m thirty years old; I’m either going to get in or out of this business.

So I wrote Platoon in six weeks, because it had been on my head. I wrote it that summer, in that apartment, when we were celebrating America’s anniversary, two hundred years.

Jimmy Carter was ascendant.

Beneath all this is a brewing consciousness, and things are changing. The country’s changing. You go through the dark years, ’72, ’73, we’re still in Vietnam, then comes Watergate, Nixon resigns, and then you’ve got Jimmy Carter becoming president in 1976.

Carter at the Democratic convention in New York City is a huge, very big, spontaneous moment. You were seven then. You probably don’t really remember it. But ’76 was amazing, it was like Obama in 2008, you know? It was a new turn. And I was proud to be a Democrat and vote Democratic.

Then four years later I found myself voting for Reagan in ’80, because Carter’s presidency was, partly thanks to the media, a shambles. But in ’76, Carter was incredible, that election was so exciting! The convention at Madison Square Garden!

Ron Kovic was there. That’s the denouement of Born on the Fourth of July: Ron speaking there.

I didn’t know him then. His book was optioned two years later. But that summer of ’76 it all turned around for me.

I just felt it was a great script, Platoon, and it took off right away. It was optioned in two weeks. And right before it was optioned I moved out to LA to a small hotel room, and Marty Bregman[15] wanted me back in New York City to work with Al Pacino[16] on Platoon, and Sidney Lumet[17]. It was so exciting. I was in with the big leagues. But then Lumet said, I just can’t go into a jungle. At my age, I can’t make that kind of picture anymore. He wanted to do stuff that was a little bit easier on him. He had a very scheduled life, Sidney. He left the apartment at 9:15 every morning. He liked his crew, his scene, to make movies on the clock, like Woody Allen. I forget what happened next, but Platoon didn’t get made then. The option lapsed.

The Platoon script did get me into Midnight Express, which was a surprise hit, a very low-budget movie at Columbia—the bottom of their rung.

When I interviewed Billy Hayes[18] I conflated him with myself because I’d been busted and I hated the authorities.

But it turns out Billy was much more than what he said in the book. He’d cowritten the book, more like had it ghostwritten, and the book is what I based it on, because Peter Guber[19] had created the project[20]. But Billy was never honest with the guy who wrote the book or with me. He later clarified to me that he’d smuggled hash out of Turkey three previous times[21]. I swear on my life, if I had known Billy Hayes had smuggled hashish before having the experience he wrote about in the book, I never would have written the film the way that I wrote it.

The Right loves to think of you as “muckraking left-wing filmmaker Oliver Stone,” and yet you’ve been accused of being sexist, of being racist against the Turks in Midnight Express, bigoted against Cubans in Scarface, and on and on. How do you feel about that? Can you even talk about that?

In relation to what? Which film do you want to talk about?

Well, I guess we could start with Midnight Express, and maybe pick up the others later, as we deal with them in your timeline.

I know you’re very sensitive about those particular charges about Midnight Express: that your script is racist against the Turks. You’ve said that the script is not so much about the criminal justice system in this particular country, Turkey—that it’s more about injustice generally, and more specifically as it pertains to people who end up in jail for drug offenses, like you did.

That’s what it was to me, and that’s why I conflated my experience and Billy’s, because my script wasn’t about the Turkish people per se. In fact, my proof of this is the speech I gave at the Golden Globes after I won there for screenwriting in 1979. In a speech that may have been incoherent to some people, I was saying, essentially, You cannot condemn Turkey. You cannot just condemn Turkey, you must look into yourselves and see what we do here on American television with all these cop shows, where you show these ridiculous drug dealer caricatures and the cops are always busting them. You’re creating an environment of the war on drugs, creating enemies all over the world, and above all, you’re being hypocrites. This is what I was saying. And as a result, I got booed off the stage the moment the speech turned on America.[22] So why would I say all that if the movie was only about Turkey?

But I think it’s my fault, because I conflated two things: Billy’s story, and my anger at being busted in San Diego for two ounces of grass and being in San Diego jail, facing federal smuggling charges of five to twenty years, and not getting any legal attention until finally I got a phone call to my father and we got the lawyer to come in and see me.

Tell me more about your drug bust, and how you got out of jail.

Dad had to pay the lawyer fifteen grand. If I had stayed in jail, I would’ve faced one of two judges. One of them was in on Tuesdays and Thursdays. With that judge I would’ve gotten probably three years and I could’ve gotten out under parole. And the other judge, Monday, Wednesday, Friday—the other prisoners told me all this—was a ball breaker who probably would’ve given me fifteen years, and I would’ve gotten out in maybe three to five.

All this for two ounces of grass! That’s pretty heavy bullshit. And the guys who were in there were heavier users, but they were stuck in there for six or more months waiting on a trial! There was nobody who’d see them!

So that system was what I was really pissed off about.

A system where guys who didn’t have your connections to money or influence were just going to rot in jail indefinitely?

Yes. I realized the system was rigged: They were all blacks or Hispanics in jail, very few whites, and I was lucky to get out.

So when I went over to meet Billy, I suppose I took his story under my skin and tried to make it an antiauthoritarian story.[23] If Billy had told me he’d smuggled drugs three times before he got caught, I wouldn’t have done the story the way I did. I couldn’t have approached it with the innocence thing that I did.

I was looking at it as my story, in a way. So, Fuck you, Turkey means Fuck your system—fuck you, the Man.

And it was misunderstood, and I didn’t apologize. I said I regretted that the film was misunderstood. That’s what I told the Turkish press. I never apologized, nor should I have.

Why do you think you shouldn’t have had to apologize?

Because the fucking penal system in Turkey was abusive, and it was condemned by international human rights groups.

Well, the movie certainly made that clear. “Turkish prison” was a synonym for “hell on earth” for years after that, mainly because of Midnight Express.

Yeah, the movie was seen as an anti-Turkish thing, and the tourist trade to Turkey dropped right off.

After Midnight Express, I was approached by several Armenian groups to write a movie about the Armenian genocide in Turkey. There was a lot of money behind it. Frank Mankiewicz, our press representative on JFK before the movie came out, was hired by the Turkish government in those years after the film came out, to repair the Turkish image. He told me some funny stories about that.

Anyway, after Midnight Express, my stock went way up. Somewhere around there, Bregman came back and asked me to work on Born on the Fourth of July, which he’d optioned from Ron’s book. He’d had another screenplay written by another young writer that was not very good, and I’d gone into that whole process while Midnight Express was going around the world.

When did you first read Born on the Fourth of July?

’75 or ’76, and it was well received. It was on the front page of the New York Times Book Review. Got a lot of attention. The book is a very poetic, structured, fragmented story. It was published only a year after the Vietnam War had ended. I was avoiding material like that, frankly. Martin Bregman, the producer who had optioned my screenplay Platoon, brought it to my attention—he thought I’d be perfect to write this for Al Pacino.

William Friedkin wanted to direct Born, since he was a legend at the time. He was living in Paris with Jeanne Moreau.[24] We were there, talking to him about how to do it.

What advice did Friedkin give you? And did any of it find its way into the movie in 1989, when you finally did get to direct it?

The structure of it was Billy’s idea. He said, “Keep it straight, do it as a linear narrative. It’s good corn.” The script had been very fragmented up to that time, so we took his advice. I wrote the script with Ron’s help, and talked to his friends. I knew a lot of the story from my own experience, but that became the reentry movie I always wanted to do. That was a painful writing process, and we geared up with Pacino, but the money wasn’t quick to come because it was a dour subject.

Friedkin dropped out to do The Brinks Job,[25] and I was so pissed at him, because Brinks was an awful movie. I just felt, in my heart, Billy, you’re wrecking your career! If there’s one movie you should do, it’s this one! I just knew he’d do a great job! Marty Bregman brought in Daniel Petrie,[26] who was a competent director and a nice man, very nice to me. We rehearsed the whole damn thing. Marty kept promising German money, and Universal would distribute it reluctantly. Dan brought in very fine actors, it was a great rep company, and I saw the whole thing rehearsed. Obviously, I was rewriting, rethinking every day. Al was, to me, a god, and he was good. I saw him in the wheelchair. But he was mid-thirties, whatever?

If that was 1978, he was thirty-eight.

He was so good! It was like watching a Shakespearean performance. He was on fire.

This stood me in good stead later in time, because it was a way of learning. Al didn’t have faith in Dan, although I did. That was always an issue. At the same time, Marty’s money never was really there, so the project fell apart with three weeks to go. All the locations had been picked. Ron was so heartbroken. He was furious. You have to realize, he didn’t know how many days he had left in the chair. I was really depressed also. So I said, Listen, if I ever get somewhere in Hollywood, I will come back and make this. He remembered that and always thanked me for it ten years later.

It took a long time for you to realize the dream of seeing those Vietnam films on the screen.

I had no idea that would be the case, because by this time I’d gone through too much and it was clear that they didn’t want to make those kinds of movies. These two movies were too dark, they were downers. Everyone had read these scripts. I felt like a prostitute, and just forgot about it.

The only one who really believed in me was Michael Cimino.[27] He actually came to me because he’d read and loved Platoon, and said, “I’d like you to work with me on Year of the Dragon,” which he was developing from an interesting book by Robert Daley. After Heaven’s Gate, Michael had to make a deal with the devil, Dino De Laurentiis,[28]Dragon, I took half a fee. Since Michael liked Platoon so much, and Dino liked Michael but didn’t care about me, Michael said, I want Oliver to direct Platoon. I’ll produce it. Dino said, “Sure,” because he wanted Michael, but he made sure to cut my fee in half, which had been established at a high rate on Scarface. And he never fucking made Platoon.

[1] Small-statured, French-born actor who played the villainous Nick Nack in the James Bond film The Man with the Golden Gun (1974); died in 1993 of a self-inflicted gunshot wound.↩

[2] Brazilian-born film director and producer; best known for the anti-Nazi propaganda film Went the Day Well? (1942), adapted from a Graham Greene story.↩

[3] 1919–2004; German American actress and drama teacher, notably at New York’s Herbert Berghof Studio, and author or coauthor of books about acting that are still used in drama classes; blacklisted in the 1950s.↩

[4] 1927–1997; film, TV, and theater actor; Prizzi’s Honor (1985), National Lampoon’s Christmas Vacation (1989); Dr. Finkelstein in Tim Burton’s The Nightmare Before Christmas (1993).↩

[5] 1924–2014; cinematographer of nearly thirty years’ experience by the time he hooked up with Stone; Ladies and Gentlemen, Mr. Leonard Cohen (1965) and Rebel High and Zombie Nightmare (both 1987).↩

[6] American television series that aired on ABC from 1977 to 1984. It starred Ricardo Montalban as Mr. Roarke, the owner of a private resort where guests could pay a high price and live out their fantasies. Villechaize (who did not appear in the final season) was his sidekick, Tattoo.↩

[7] Film producer and distributor; founder of the Movie Network and other early scrambled, over-the-airwaves pay-per-view channels; producer of the Porky’s series.↩

[8] Cofounder, with James H. Nicholson and Roger Corman, of American International Pictures (AIP).↩

[9] Cinerama Releasing Corporation (1967–78); created when the Pacific Coast Theater Chain purchased Cinerama, Inc., to distribute Cinerama-format movies plus select foreign films and movies made by the ABC network.↩

[10] Italian talent agent and producer of The Mission (1986), written by Bolt.↩

[11] 1924–1995; English screenwriter; Lawrence of Arabia (1962), A Man for All Seasons (1968), Ryan’s Daughter (1970).↩

[12] American heiress kidnapped in 1974 by the Symbionese Liberation Army, an urban guerrilla group, and brainwashed into joining them.↩

[13] French Algierian war film (1966) directed by Gillo Pontecorvo. For more on Pontecorvo, see footnote 66, chapter 6, page 290.↩

[14] Symbionese Liberation Army leader; shot himself after the house he and other members were in caught fire during a shootout with police.↩

[15] Producer of twenty-nine films, including Serpico (1973), Dog Day Afternoon (1975), and Carlito’s Way (1993).↩

[16] 1940– ; “Who’s being naive, Kay?” “Attica! Attica!” “Say hello to my little friend!” “Whoo-ah,” “Favor gonna kill you faster than a bullet.” “All I am is what I’m going after.”↩

[17] 1924–2011; prolific American director, often in a naturalistic New York mode. 12 Angry Men (1957), The Pawnbroker (1965), Dog Day Afternoon (1975), Network (1976), The Verdict (1982).↩

[18] William Hayes was given a life sentence for smuggling hashish into Turkey on October 7, 1970, escaped from prison on October 2, 1975, and wrote the autobiographical book on which the Stone-scripted Midnight Express (1978) is based.↩

[19] Film and music producer; currently chairman and CEO of Mandalay Entertainment; and co-owner of the Golden State Warriors (basketball), the Los Angeles Dodgers (baseball) and the Los Angeles Football Club (soccer).↩

[20] Nancy Griffin’s 1996 book Hit and Run, a critical account of Guber’s tenure running Sony Pictures with movie and music producer Jon Peters, credits Guber with packaging Hayes’s story with Stone’s script, British ad man Alan Parker’s direction, and Giorgio Moroder’s pulsing electronic score to make a serious but highly exploitable thriller that would eventually earn $34 million and win six Golden Globes and two Academy Awards (including Stone’s award for adapted screenplay).↩

[21] According to a November 14, 2014, profile of Hayes by The Daily Beast, “Hayes wasn’t a green American nabbed on his first drug smuggling attempt, but a small-time runner who’d made three trips prior to getting nabbed—in April 1969, October 1969, and April 1970. On each trip, he’d purchase two kilos of Turkish hashish for $200 apiece, tape them to his torso (there was no airport security back then), and sell it in the States for $5,000.”↩

[22] No video or transcript of this speech exists online, unfortunately.↩

[23] In a January 9, 2004, interview with the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, Hayes said, “I loved the movie, but I wish they’d shown some good Turks. You don’t see a single one in the movie, and there were a lot of them, even in the prison. It created this impression that all Turks are like the people in Midnight Express. . . . I wish they’d shown some of the milk of human kindness I (also) witnessed.”.↩

[24] French actress; star of François Truffaut’s Jules and Jim (1962), among others. Friedkin’s wife from 1977 to 1979.↩

[25] Peter Falk starred in this film about the real-life 1950 robbery of nearly $3 million from a Brinks vault in the North End of Boston. While generally well received by critics, Friedkin later said the film “has some nice moments, despite thinly drawn characters, but it left no footprint.”↩

[26] Director of Lifeguard (1976), The Betsy (1978), Fort Apache the Bronx (1981), and the TV movies Sybil (1976) and The Dollmaker (1984). Producer of twenty-nine films, including Dog Day Afternoon, Serpico, Scarface, and Carlito’s Way.↩

[27] Director of The Deer Hunter (1978) and Heaven’s Gate (1980), a huge financial and critical flop. Stone cowrote Cimino’s first film after Heaven’s Gate, Year of the Dragon (1985), discussed in chapter 3, pages 119–27.↩

[28] 1919–2010; Italian film producer as known for his grandiose demeanor as for his collaborations with Federico Fellini, Ingmar Bergman, David Lynch, Ridley Scott, and other notable directors.↩