Back to selection

Back to selection

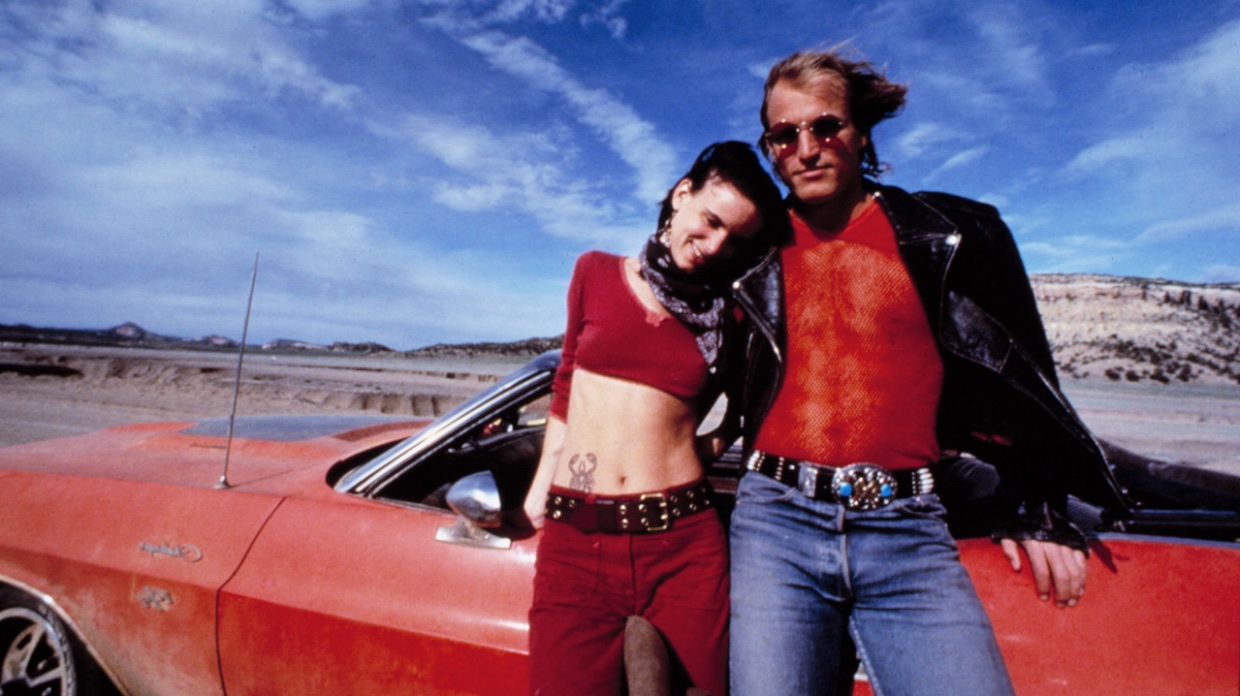

Natural Born Killers, The Virgin Suicides and More: Jim Hemphill’s Weekend Viewing Recommendations

Natural Born Killers

Natural Born Killers From 1986, the year in which he made two flat-out masterpieces (Salvador and Platoon) to 1995, when he directed his boldest and richest film to that point (Nixon), Oliver Stone was on a streak like no other filmmaker has ever had before or since. Ten films in ten years, many of them (Born on the Fourth of July, JFK, The Doors) enormous epics and all of them ambitious attempts to assess where America had been, where it was, and where it was going. The scale and depth of Stone’s work during this period is equaled by the diversity of tone, as the director alternated between earnestness and irony, tragedy and satire, and radical experimentation and Hollywood classicism while jumping back and forth between genres. Stone’s range was never more evident than in 1994, when he followed the contemplative, spiritual Vietnam melodrama Heaven and Earth with the confrontational, nihilistic crime drama Natural Born Killers, which is currently streaming on FilmStruck. Based on a script by Quentin Tarantino that Stone, David Veloz and Richard Rutowski heavily rewrote, Natural Born Killers tells the story of Mickey and Mallory, young mass murderers who are deeply in love — and deeply disturbed. Riffing on romantic fugitive movies like Bonnie and Clyde and Badlands as well as Roger Corman exploitation flicks and more serious explorations of violence like A Clockwork Orange, Stone follows Mickey and Mallory as they shoot, stab and slash their way across the American Southwest. All the while they (and the audience) are bombarded with images of 20th-century chaos that not only play on television sets, but also seem to be projected onto the landscape itself. Stalin and Hitler give way to O. J. Simpson and the Menendez brothers in a sensory assault that raises complicated questions about the relationship between mass communication and violence.

Many movies that are controversial in their time often seem tame and irrelevant years later, but Stone’s depiction of a media-saturated age in which violence and cruelty drive news coverage and that coverage, in turn, encourages desensitization is more relevant today than it was at the time of the picture’s release. Like The Wild Bunch and Taxi Driver, Natural Born Killers retains its power to provoke and unsettle decades after the fact because, like those two films, its shock value derives not from base sensationalism but from a profound understanding of the dark side of human nature that civilization attempts to obscure and repress. Stone’s movie is pure id, and his fearless celebration of Mickey and Mallory’s romantic spirit aligns with his equally fearless presentation of brutality to create a disconcerting experience in which the audience is forced to question its own views about violence and violence’s relationship to society. (Stone’s refusal to provide easy answers and his suggestion that the audience is complicit is undeniably one reason why the picture repulses as many viewers as it engages.) The conceptual audacity is matched with a visual style as radical as anything ever seen in a major studio release. Mixing black-and-white and color, celluloid and video, 8mm, 16mm and 35mm film stocks, cinematographer Robert Richardson creates a collage effect in which every image contains both its own internal beauty and a symbolic function as part of a larger social statement. He also uses lighting to convey inner states in conjunction with what Stone calls “vertical editing” — a character will appear one way in a naturalistically lit scene, but a brief cut in the middle of that scene to a different film stock and lighting set-up reveals the way that character really feels about the situation. Stone’s mastery of dozens of different cinematic idioms makes Natural Born Killers one of those movies that, like Citizen Kane or The Conformist, can be endlessly studied and analyzed by film students who want to broaden their visual literacy. In this one movie, scenes are shot like sitcoms, action flicks, news broadcasts, avant-garde experimental films, 1940s noir and more. It is a stunning tapestry that feels surprisingly cohesive, thanks to the movie’s overall message about the pervasiveness of mass media in our lives.

On the Blu-ray and DVD front, this week sees the release of two exemplary Criterion editions, Sofia Coppola’s The Virgin Suicides and Jim Jarmusch’s Dead Man. Released in the glorious year for movies that was 1999 (the year of Magnolia, Being John Malkovich, The Limey, Eyes Wide Shut, Fight Club, Election, Three Kings and so many more), Coppola’s debut feature remains one of the greatest films ever made about the loneliness and confusion of teen life, about the mysteries that exist between adolescent boys and girls, and about the combination of hypersensitivity and utter cluelessness that afflicts so many teenagers and adults alike. Faithfully adapting Jeffrey Eugenides’ novel yet completely transforming it by physicalizing its ethereal fever dream style, Coppola pulls off a minor miracle, creating a film that is simple and clear but jammed to the hilt with sophisticated meditations on loss, memory, aging, innocence, death, and beyond. In some ways it remains the director’s most confident and satisfying feature, utilizing sophisticated color coding, a hypnotic integration of music and camera movement, and performances remarkable in their intersection between clarity and complexity to create an achingly beautiful collage of longing and regret. Mournful and beautiful in its own way, Jarmusch’s 1995 Western Dead Man consists of, like Coppola’s film, a stripped down plot that yields the dense thematic textures and emotional resonances of a great novel. Johnny Depp plays William Blake (no relation to the poet, though he’s constantly mistaken for him throughout the film), an accountant forced to go on the run when he kills an industrialist’s son in self defense; though the plot is that of a chase film, Jarmusch employs an episodic structure in which momentum is constantly thwarted – a wry metaphor for the country whose progress (and lack thereof) the director is interested in charting. Touching on everything from America’s gun culture to its relationship with fame and matters of race and class, Jarmusch follows in the tradition of great 70s Westerns like Little Big Man and Ulzana’s Raid in both honoring the conventions of his genre and shattering them, exposing the tensions and contradictions at the heart of American identity.

A very different but equally trenchant exploration of American character comes to Blu-ray this week in the form of Joe, a 1970 time capsule that was hugely successful at the time of its release, then was relatively forgotten, and now feels increasingly relevant in the age of Trump. Directed by John Avildsen from a savage script by Norman Wexler (his first, before he would go on to even greater success and esteem with Serpico and Saturday Night Fever), Joe is a bizarre premonition of two very different cultural touchstones that would come later, All in the Family and Taxi Driver. The title character played by Peter Boyle is a cross between the former’s Archie Bunker and the latter’s Travis Bickle, but he’s far less appealing than either – Boyle plays his resentful, bigoted character without mercy, without charisma, and without sentiment. Feeling the squeeze of working class life, he’s a tightly wound ball of grievances that he aims everywhere but their source, and if the movie’s style is a bit dated, Joe’s cultural attitudes feel sadly contemporary. Joe is one of two excellent releases this week from Olive Films, the other being the Blu-ray edition of John Boorman’s Hope and Glory. Released in 1987, Hope and Glory is Boorman’s autobiographical film about World War II as experienced by a young boy growing up in a London suburb during the blitz, and it works superbly as an irony-tinged nostalgia piece that combines awe-inspiring spectacle with affecting moments of intimate detail. For cinephiles and Boorman enthusiasts, the movie operates on an additional level, as a delightful portrait of the film director as a young man; in moments that are as fleeting as they are funny and charming, Boorman depicts the instances in his young life when his obsessions were formed, giving a glimpse at the formation of the psyche that would later create cinematic treasures like Point Blank, Excalibur, and The Emerald Forest. This idiosyncratic personal component distinguishes Hope and Glory from similar films like Steven Spielberg’s Empire of the Sun, which was released in the same year, but a knowledge of Boorman’s oeuvre isn’t crucial to appreciate the picture – its touching, often hilarious script and Boorman’s delicate sense of craft are their own rewards.

Jim Hemphill is the writer and director of the award-winning film The Trouble with the Truth, which is currently available on DVD, iTunes, and Amazon Prime. His website is www.jimhemphillfilms.com.