Back to selection

Back to selection

“We Try Not to Think”: Véréna Paravel and Lucien Castaing-Taylor on De Humani Corporis Fabrica

De Humani Corporis Fabrica

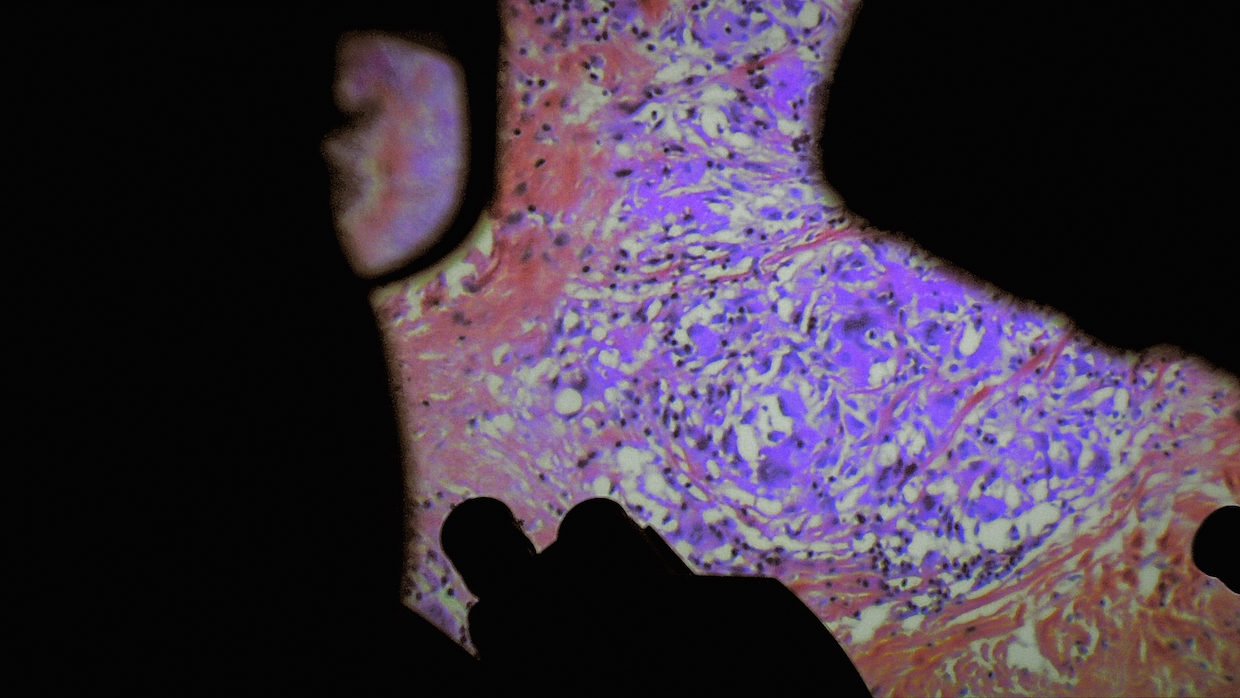

De Humani Corporis Fabrica It was only a matter of time before Sensory Ethnography Lab explorers Véréna Paravel and Lucien Castaing-Taylor went inside—deep inside. Shot at eight different French hospitals, De Humani Corporis Fabrica intermingles imagery from within and without the human body, observing patients and listening in on surgeons during operations with special cameras and medical equipment. Immersive in different ways from their masterpiece Leviathan, and even more hypnotic than Caniba in aligning the screen’s surface with the textures of tissue, Paravel and Castaing-Taylor’s latest film takes its title from Vesalius’s groundbreaking 16th-century anatomy text, de- and re-familiarizing us with the interiors and exteriors of our flesh, and the systems used to navigate and contain them. Put another way, you could do a lot worse than a recent, unrelated tweet by filmmaker Zia Anger:

mostly when i think of all the stuff inside me, muscles, bones, nerves, veins, organs, etc etc and how much it there is just working away I get so overwhelmed and existential I cant hardly stand it

— Zia Anger (@AngerZia) June 2, 2022

De Humani Corporis Fabrica inaugurated the second week of Directors’ Fortnight (Quinzaine) and screened on the same day as David Cronenberg’s Competition title Crimes of the Future, another film that thrives, as Paravel said of De Humani, in “the space between beauty and horror” and features opening credits against a vermilion tissue-like background nearly identical to laparoscopic shots from De Humani. I interviewed Paravel and Castaing-Taylor, who teach at Harvard University (with programmer and scholar Abby Sun as teaching assistant), at the Cannes Film Festival, and as ever, conversation was especially stimulating as the film remains a living thing to them, open to inquiry and lovely consideration, at once spontaneous and architectonic. We spoke over the din at the Plage de la Quinzaine about how they shot the body/bodies, disorientation as reorientation, and finding a Dionysian ending. The film enters US release April 14 via Grasshopper Film.

Filmmaker: What cameras are you using in the film, aside from the medical imagery?

Castaing-Taylor: The medical imagery is the most important. But we used “lipstick cameras.” They’re very specialized and kind of an anachronistic technology. They were used in Formula One cars, with a transmitter so people could watch live in the car, but the principal use is industrial—not surveillance of people but of machinery, like in mills, hard-to-access places. They’ll install them permanently, and it’ll just be a permanent bead on this one cog to see whether it’s worn down. Our camera broke down the whole time.

Paravel: The camera was not working by itself, so we had to create a system where we could see what we were filming. So, we asked Patrick Lindenmaier, our colorist and tech genius, to create a system where we would have a harness, with a monitor here [at chest level]. The camera evolved through the film, because we started with a different camera but were not really happy with the image. So, we were using this lipstick camera and sending it back to Zurich, and he would create another system to help us synch with the sound. The way we recorded was very archaic, because we would download the medical imagery of the surgery, and at the same time we were recording outside of the body and doing sound separately. At the end we would synch everything, so everything would align in a single timeline, then we could go from the inside of the body to the outside.

Sometimes we also had the ceiling [“scialytic”] camera that the doctors used. They would often use this imagery to record and teach their surgery, when it’s an interesting surgery and they want to show a colleague, or to watch their own gestures, or to share with medical students. So, we would have the camera from the ceiling, the laparoscopic camera, our own camera, plus the sound, and everything was aligned so we could go from one camera to another.

Castaing-Taylor: Ultrasound, X-rays, MRIs—that was the hardest to synch up.

Filmmaker: When you’re filming with the lipstick camera, are you right there next to the surgeon?

Paravel: Yes.

Filmmaker: At times it felt like you weren’t physically there, as if the camera was remote.

Paravel: Really?

Castaing-Taylor: It was always moving, wasn’t it. Oh my god, the amount of hours we were training to make those moves! I was watching yesterday, and I thought, these moves are so awkward and unsmooth.

Paravel: Me too.

Castaing-Taylor: Atrocious!

Filmmaker: But it must be a challenge with such a small camera! Every little movement is significant.

Castaing-Taylor: Have you seen Hale County This Morning, This Evening? Remember the locker-room scene in the gymnasium? Was he filming or was he absent? Did he put the camera down and leave it, or was he there? I don’t know if he was there or not. Richard Brody hypothesized that he was not there.

Paravel: In our case, we were always there. But also it was adapted to the operating room, the sterile environment, where you cannot be too close to the doctor physically.

Castaing-Taylor: Plus it burned! The camera got so hot we had to cover it with towels or gloves or anything we could find in the operating theater so that we wouldn’t burn ourselves. Sometimes we would come away with blisters and burnt fingers from holding it.

Filmmaker: From the electronics overheating?

Paravel: Because it was not perfected. It got perfected over time.

Castaing-Taylor: [Each camera] was like $300. We went through a few.

Filmmaker: How was it to work out the lighting for these cameras?

Castaing-Taylor: I don’t know if you remember the urology scene?

Filmmaker: It’s hard to forget.

Castaing-Taylor: When the probe is being removed from the penis and you can see all the scrubs around it, there’s a conversation between the doctor and one paramedic in particular about the block, and how officially organized it is, and whether they need more personnel and how many people are unemployed in France… In the middle of that shot, we don’t do anything but the camera cuts out and it goes basically white—completely overexposes. It would suddenly go—without any rhyme or reason, without any deliberation on our part, for reasons unknown to it and us—from underexposed to overexposed, or black-and-white to color, or the color temperature would change. All of the manual settings would just be overridden willy-nilly.

Filmmaker: Those are tough conditions to work under.

Castaing-Taylor: If you remember the morgue, one shot is almost black and white. The color grader did Pedro Costa’s first films like In Vanda’s Room and so on—he’s technically extraordinary. Amazingly, he was able to find data in the files that no other collaborator in the world could find, because of how they mark the files. He was able to decode the files, find this hidden [visual] information in there and convert it into something usable.

Filmmaker: In using the imagery from the medical equipment, did you manipulate the colors at all?

Paravel: [In the gastrointestinal sequence] at some point it becomes red and green. They do that themselves, to see the little things inside and make sure they are not missing any polyps. This is not our manipulation.

Castaing-Taylor: There’s a film from a decade ago by Yuri Ancarani, using a Da Vinci [surgical] robot [Da Vinci, 2012]. He used dyes. A doctor cousin of mine thought it was a fake advertisement for Da Vinci.

Filmmaker: I’m curious what sort of aesthetic criteria you brought to the medical imagery. Are you thinking of film grammar in the same way when working with that sort of continuous imagery?

Castaing-Taylor: We don’t think. We do think—we try not to think. We fail to think. But we are mostly interested in what happens when we half-succeed. I suppose there were three different layers. One is our intentions, which change from hour to hour, from person to person, from day to day. The next morning, we ruminate, change positions and go back. Our conscious intentions mutate in ways we can’t anticipate. And then most of the thought is unconscious, because it’s deeper and we can’t access it usually—whether it’s our images, where we control it a bit more, or in the downloaded images, where we selected which camera to use, which operation, when to start and stop.

Regardless of which kind of imagery it is, what’s interesting to us is the surfeit of aesthetics or of meaning or of presence. This residue of presence, one senses, isn’t about even our unconscious inclinations or conscious thoughts. That “excess of being” is there latent in every image, whether we nominally have more agency in recording it or not. So, I don’t think it’s radically different [between kinds of imagery]. Obviously there’s a grade of remove to medical imagery, even though we’re less passive than it might appear. Sometimes there were different kinds of medical cameras that go inside the body, so we would shoot one and not the other. So, we would literally be controlling that point of view, but obviously with that kind of imagery we have less agency than we do with our own. And this third level of meaning or whatever the word is—aesthetic resonance—is more present, easier to glean, more intriguing, more divorced from our intentions. But the relationship we came to by hook and by crook is something that we did not verbalize. It was the hardest film ever to edit. Excruciating.

Filmmaker: It’s all a visceral experience, literally. It can also feel vertiginous or even disorienting, even when we’re not inside a body, but outside, as in the sequence walking with two elderly women through the senior citizens ward.

Castaing-Taylor: You mean [disorienting] psychically or spatially?

Filmmaker: Psychically and to a certain extent spatially. Were you trying to play with our orientation in terms of unsettling the viewer with shifts in centeredness?

Paravel: I think yes.

Castaing-Taylor: I think no.

Paravel: Yes and no. I think we unconsciously re-created that, because this is the way it works in hospital. You have all this circulation: people are moved from one ward to another, patients are moved to their rooms and to their operating rooms, organs are moved from one body to another, fluids are being transported from one lab to another. So, there is always this movement and circulation. The flux of the hospital resembles the blood circulation inside the body. I think that came naturally, because this is the way you navigate a hospital.

But for me the purpose was not to create a sense of disorientation. We were not interested in disorienting the viewer but in trying to install you in some places and reveal later where you were. I don’t know if you knew you were in an urethra before the camera pulls you out of it. So, sometimes we play with this to show you an interior space or territory, where you can get your bearings but don’t know exactly what it is. We allow you to see things you’re not usually used to see, then suddenly the disorientation doesn’t come from being inside, it comes from when you get out. You know where you were—in a head, a urethra, an abdominal cavity.

Castaing-Taylor: When we had our friend design the camera system, his idea was that we ourselves would film with a laparoscopic camera outside the body. Then we determined that the medical cameras were all between $800,000 and $1.5 million, and they all turn out to be attached and weigh a ton when plugged in. We couldn’t have the mobility that we wanted, and their main focus is half a centimeter from the lens. So, we decided not to film with one of those. We had Patrick make this camera so that the optics would generate an aesthetic sensibility akin to that generated by laparoscopic cameras. They had very long depth of field, very wide angle vision, and it could focus extremely macro up close.

So, the idea then was to generate reciprocities between interiors and exteriors which could make us rethink the singularity of these supposedly discrete bodies and between interior and exterior. We could call that destabilizing or disorienting, or we could also call it orienting or reorienting. When we’re filming in the senior citizens’ ward, the geriatric hospital, we weren’t either using the camera equipment in intentionally misleading ways or disorienting people, but on the contrary using a camera that would somehow generate imagery that would be of a piece with different corporeal interiors.

I don’t think either of us is interested in disorientation in some shock sense, or like some horror film, or for suspense in and of itself. But it is true that we go through most of our filmmaking lives being oriented, and it does seem to me that despite our desire to be oriented, we’re often disoriented and uncomprehending, and there are ways in which our brains and imaginaries are activated when we’re not under the illusion that we understand everything. Those ways are often more generative, especially with documentary that’s so compositional and informational and didactic.

The first cut of the film was ten hours and one minute, longer than Shoah. It was riddled with testimony by the doctors. Most of the hospitals that we filmed in are university teaching hospitals. So, there’s a lot of verbal exegesis explaining to the residents what was going on. That gave spectators the sense that they understood the point of the surgery, what the diagnosis was, sometimes what the prognosis was, etc. But that ends up anesthetizing us to a different way of engaging with the body in all of its potentiality. You’re directed toward a specific kind of narrative, an explicative kind. Cutting it down from 10 hours to two hours, we spent a lot of the time trying to retain snippets of dialogue that would be interesting but wouldn’t be interpretively too revealing.

Filmmaker: I think the reason I was thinking about disorientation is that biological footage can give an illusion of mastery. And this film is trying not to give that feeling of mastery.

Castaing-Taylor: I feel that’s what we tried to do unwittingly in Leviathan, which is to use GoPros not to show this heroic surfer or snowboarder doing some macho, probably male heroics, but to diminish and relativize the viewer in this larger cosmos. It sounds like we engaged unwittingly in a similar endeavor here.

Filmmaker: It’s just one part of it for me! I’m still working through it.

Castaing-Taylor: We haven’t begun to work through it.

Filmmaker: About the final sequence—

Castaing-Taylor: Too long.

Filmmaker: You think it’s too long?

Paravel: No, it’s good!

Filmmaker: How did you envision this scene? [The final sequence takes place in a large recreation room for doctors with outlandish murals and low party lighting.] It felt like a combination of the infernal, and like being in a cave where I’m looking at the walls with a torch. It’s also a Dionysian end to the film.

Paravel: Interesting, I hadn’t thought of the cave. For me it was more like a religious fresco, how you would film the Sistine Chapel or something. It’s almost the apotheosis of the film, where spirituality, sex, death collide. But now I like to see it like an archaic painting in a cave. [For the doctors] it’s basically the last place where they can let go of all the violence they have been witnessing all day—because the doctors have to be God most of the time, and they have this great responsibility. They spend their day transgressing the body, violating the body, perforating it, penetrating it, cutting it. And they witness death every day. And you know what place this room is? Every single French public hospital, not private, has a cafeteria that’s called the Salle de garde where only the doctors and students can enter.

Castaing-Taylor: But not the nurses.

Paravel: This is where they eat. They are covered with pornographic frescoes. This is also where they have parties sometimes. What you see on the painting are the faces of real doctors who are operating.

Castaing-Taylor: Still operating or retired or in some cases died.

Paravel: And I don’t think it’s too long. For me it does the same job for the viewer as for the doctors. It’s the space and the condition for them to be able to exorcise [things].

Castaing-Taylor: Basically it’s their way to de-sublimate. They need to put a distance between themselves and their patients. They need to objectify and instrumentalize them to some degree, superficially at least, in order to be able perform all these perverse transgression on their bodies, even if it’s with a view to repairing them, healing them. But obviously that is an extraordinarily perverse and powerful and overwhelming position to be in, and their transgressions also exact a toll on themselves. So I think they need moments of liminal, carnivalesque, anti-structural, cathartic communitas like this to allow everything they repress, in order to carry on with their day jobs, to surge to the fore and then be sublimated again, and then carry on. It was relatively tame as a party [on screen]. They do completely orgiastic things in these spaces that we did not put into the film.