Back to selection

Back to selection

“We’ve All Gone a Bit Broke Making It”: Lucy Walker on Mountain Queen: The Summits of Lhakpa Sherpa

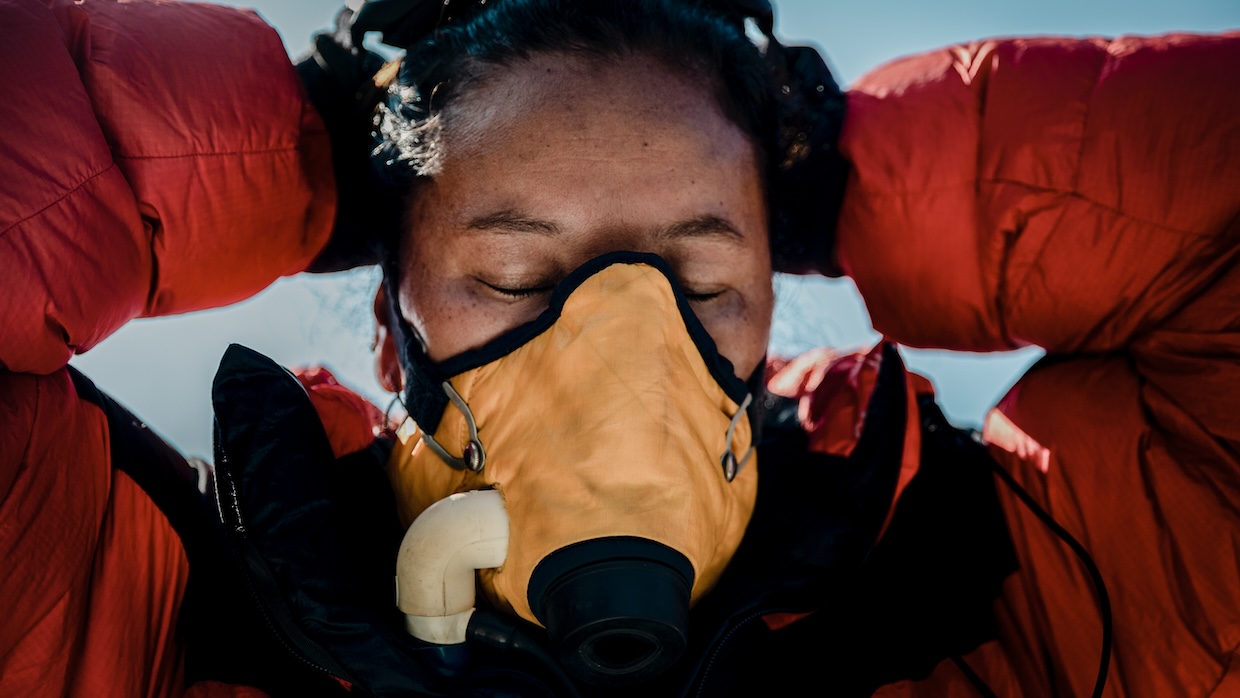

Lhakpa Sherpa in Mountain Queen: The Summits of Lhakpa Sherpa

Lhakpa Sherpa in Mountain Queen: The Summits of Lhakpa Sherpa Nearly twenty years ago, Lucy Walker was making a film on the slopes of Everest following a group of blind teenage Tibetan climbers. While on the mountain, she heard of an incident that had taken place when a male guide attacked his wife and climbing partner, a Nepalese woman named Lhakpa Sherpa.

Lhakpa’s cursed expedition was the focus of a damning book published a couple of years later, as well as a feature in Outside Magazine. At that point Lhakpa had summited Everest seven times but was living in a cramped apartment in Connecticut as an illiterate single mother, still living in fear of her now ex-husband.

Walker became intrigued by the dual nature of Lhakpa’s life as a record-breaking Everest climber with a messy personal life. She reached out to Lhakpa and gained access through her two teenage daughters, who researched Walker’s impressive documentary filmography. The British-born filmmaker has earned a reputation as one of the most skillful nonfiction storytellers working in the US today. A double Oscar nominee, her 2013 feature The Crash Reel, about the snowboarder Keven Pearce, won an Emmy and Cinema Eye award and a slew of festival audience awards. The film begins as a high adrenaline sports documentary before pivoting to become a story of recovery from traumatic brain injury.

Filmed over six years, Mountain Queen: The Summits of Lhakpa Sherpa also has a dual track narrative as a gripping mountain adventure tale and a moving exploration of family strife, as Walker skillfully and vividly recounts Lhakpa’s often astonishing life story. The documentary had its world premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival, where it was scooped up by Netflix. It’s scheduled for a global release on the platform at the end of July.

I spoke with Walker via Zoom following her European premiere at Sheffield Docfest.

Filmmaker: Can you just tell me a bit about the origins for this project?

Walker: I made a film that came out in 2006 called Blindsight about blind people climbing the mountain next to Everest on the Tibet side, to the north. It was the first time I visited that Himalayan region. I spent about six months there in 2004 and really fell in love with that culture. To fall in love with Tibetan culture is to fall in love with Sherpa culture to some extent. I also really learned how to shoot on the mountain and make movies up there. The movies that I make are not just the spectacle of the climbing, but also how to still find the emotional, intimate story. What it looks like is just stunning visually and you can frame these incredible shots, which is fantastic. But if you’re me, you also want to tell what’s actually going on for the people in the story. How do you still capture that in extremely difficult conditions and construct a film around that?

With Kevin I made a film following a winning athlete, but I was only interested in that story because he was in a really difficult position, and I was really moved [by] how he was going to move forward. The same thing with Lhakpa: I was really moved by what she’d been through, the struggles that her family was in and how that would turn out. The idea was always the structures that she climbed, mapped out over the summits of her life’s journey.

Filmmaker: What challenges did you experience while filming?

Walker: One of the most troubling things was how worried I was about the oldest daughter. She was really struggling, really traumatized—she had been through such difficult things that she was almost catatonic at the beginning. I was really concerned about her mental health. I didn’t feel like we could put the movie out in the world unless she was in a good enough place that she could handle it because, you know, safety first, you’ve got to take care of people. And I didn’t think she was in a situation where [I could] put the movie out if she was too vulnerable for what would follow.

Lhakpa’s original mission was to inspire women and girls, but at the beginning of the movie, her own daughters are in need of inspiration. They’re really struggling and barely talking to her, not really inspired by her at all. Then, through the course of that climb, you could see the one who goes [to Everest] and also the one who stays becoming completely inspired and actually really feeling like their lives are turning around. Their mental health is totally transformed. During the edit, I caught the producers and said, “I think that the kids have an arc too.”

There was a key scene where we’d already wrapped the camera. Sunny had been in her room all day, hiding or whatever. She hadn’t come out yet, and we’d given up on her coming out. The sound person had gone home; the camera was wrapped. And she comes out and she’s got the sparkle. And I thought, “Oh my goodness, maybe we can get a talk.” And I said, “Would you mind if we filmed you?” And she said, “No, actually, that’s fine. I’m just going to eat something. But you can film.” I stood there with the DOP: “Let’s roll.” And he said, “We can’t, the sound person’s gone, how I can do it?” And I said “I can do it. Let me grab the boom pole.” So, it’s not the best looking scene in the whole world, but it is that perfect example of when you get a verité moment, it’s so precious. Because these people are not actors, right? It’s a very real, authentic opening in the unfolding story of this family, and I’m so happy that we were there for it and able to take advantage of that. Then, by the end, Lhakpa’s healing her own family and inspiring her own daughters. That’s how I structured the whole story. The present-day unfolding story is that Lhakpa realises she has to reclaim a legacy by going back to Everest to inspire her own daughters.

Filmmaker: Tell me about the filming of the mountain scenes.

Walker: It took a lot of persuading of the financiers and producers to film on Everest. Nobody else thought that we could or should, and I was really insistent for a couple of reasons. I wanted people to see Lhakpa in action and see her be a fantastic mountaineer. How many times do we get a chance to see a female climber and to give her that actual visual treatment of a climbing movie? Let’s treat her like she is actually a serious athlete and get some serious athlete shots. I don’t want to just wave her off and say “Show us a photo from the summit.” If she was a man, we’d be filming this. So, I really wanted to do that. Also, I knew it would make for a better movie because we want to find an audience. I felt like this is the kind of story that can really make a positive shift in the culture. I think she’s really a fantastic role model and inspiration to other people around the world, and I knew that the film would be that much more commercial and watchable if we could get that mountain footage.

Filmmaker: To have an unfolding narrative.

Walker: Exactly. Because what else are you going to put on the screen? People don’t want to watch a whole movie set in Whole Foods. Washing dishes? Not very cinematic.

Filmmaker: So who did the mountain filming?

Walker: There’s a very specific person that does that, a high-altitude cinematographer, Matt Irving. He’s unbelievable. I collaborated with him specifically as he was the person most likely to be able to summit with her and capture it. But I didn’t know if he would. You don’t want to pressure anybody, because safety is always the priority. I mean, the real success of this movie in a way is that nobody got hurt making it, if you ask me! Because the danger is really real, and that responsibility weighs on me.

So, we collaborated very intensely and talked an enormous amount about the equipment and the shots, what we wanted. He watched me work with Lhakpa for a long time, as well as filming all the other stuff. I always feel with cinematographers that you’re better off empowering them as real collaborators. Sure, I’ve got my own ideas, but sometimes in the situation in a documentary, if you pause and wait for me to get an idea or explain to you, you’ve missed the moment.

We couldn’t afford two camera teams, so I was also excited about the Sherpas and knew that we could train them up and give them each cameras as well. They didn’t have quite as big a camera as Matt did, but we gave everybody except for Lhakpa a camera, and also explained what we wanted from them and how to get steady shots, what kind of shots we wanted and what kind of shots were less interesting, and really empowered them. And what’s really cool about this is that it’s an all-Sherpa expedition—they are the stars rather than them being support to Western tourist characters.

Filmmaker: What kind of budget was it?

Walker: We had to be really frugal. I didn’t get the five-million-dollar budget to make this movie. So, we had to be quite creative about how we allocated our resources. I never discuss budgets but would say there’s a tremendous amount of love that made up the shortfall. We’ve all gone a bit broke making it. It was a miracle that we got picked up at Toronto. I couldn’t waste an hour of the edit. It was such a lot of pressure, because I knew what movie we had and how good it was, but everyone was panicking about the market. No one wanted to put more money in. We had a very tight amount, and I just had to work my tail off.

Filmmaker: The film is rich in personal archive. Tell me about it and how you managed to find so much of it.

Walker: None of this had been gathered at all and there was no real sign that it existed. There was just my hunch knowing—for example, doing The Crash Reel, it’s kind of amazing what you can find if you start digging. I knew that there was this film shot in the year 2000, but if you look at it, there was nothing. But I thought “If we can get the dailies, if we can get the raw rushes…” That took an enormous amount of work, because it’s very difficult for producers to share their raw rushes with another filmmaker 20 years later. And just getting people to go dig up their old 2004 expedition video, especially because it had become such a sour taste. I mean, the story was not a victorious story. The story of Lhakpa was an incredibly painful memory for most people. Some of those pieces took us over a year before people said yes, let alone actually sent it to us. So, it was a huge undertaking and hugely rewarding. It makes a big difference to the quality of the resulting film, because you can really see her life’s journey in those amazing pieces of videos. I’m really grateful to the people that trust me with that footage.

Filmmaker: Can you talk me through the master interview, which she gives in her unusual version of English? Were there discussions about what language Lhakpa should give the interviews in?

Walker: There was lots of discussion about that, and we did interview her as well in Nepali. Then we found that Nepali is also her second language; Sherpa’s her first. But she does live a life speaking in English, and she did move to the US in the year 2001. She left her Sherpa village when she was 15. There is a sense in which it is considered more commercial for it not to be all in foreign language. And she communicates with her daughters solely in English. So, I think when we tried different options, it didn’t feel wrong for her to speak English. And what I found was, and the producers agreed with me, that she’s really funny, and charming, and her language tells a story.

One thing about my process is I test a film repeatedly in the edit. At every stage, every week or two, I’ll show the film to a bunch of people and get their feedback just so I can really calibrate what they’re thinking. And one of my big questions in those early screenings was “How do you feel about her language?” Because I could have gone back and picked up all the interviews in different languages. I didn’t think they were better. And the audiences that I was testing things on were like, “It helped me get to know her and understand her predicament.”

Filmmaker: Finally, just curious whether you keep in touch with your contributors after a film is finished?

Walker: Absolutely, many of them, and I really treasure those relationships. You go through these pivotal moments in people’s lives. To some extent, to make these films is to fall in love with the people that you make them about, because you bring such a loving attention. You’re observing them going through things. It’s such a privilege to be that close to somebody. I wouldn’t be able to do that if I wasn’t sort of in love with them. It’s not in a romantic or sexual way; it’s that gaze of awe and affection, and championing and witnessing that you have to have. And you want to be around for them as the film comes out, because it wouldn’t be responsible to just stick the movie out and not to be mindful of how it’s going to affect them. So, I always want to be there for that and always, to the extent that anyone wants to be friends with me, I’m also friends with them. It doesn’t stop when the movie’s out, because everything continues to unfold.