Back to selection

Back to selection

Extra Curricular

by Holly Willis

Gale Force Cinema: Studying with Luis Recoder and Sandra Gibson

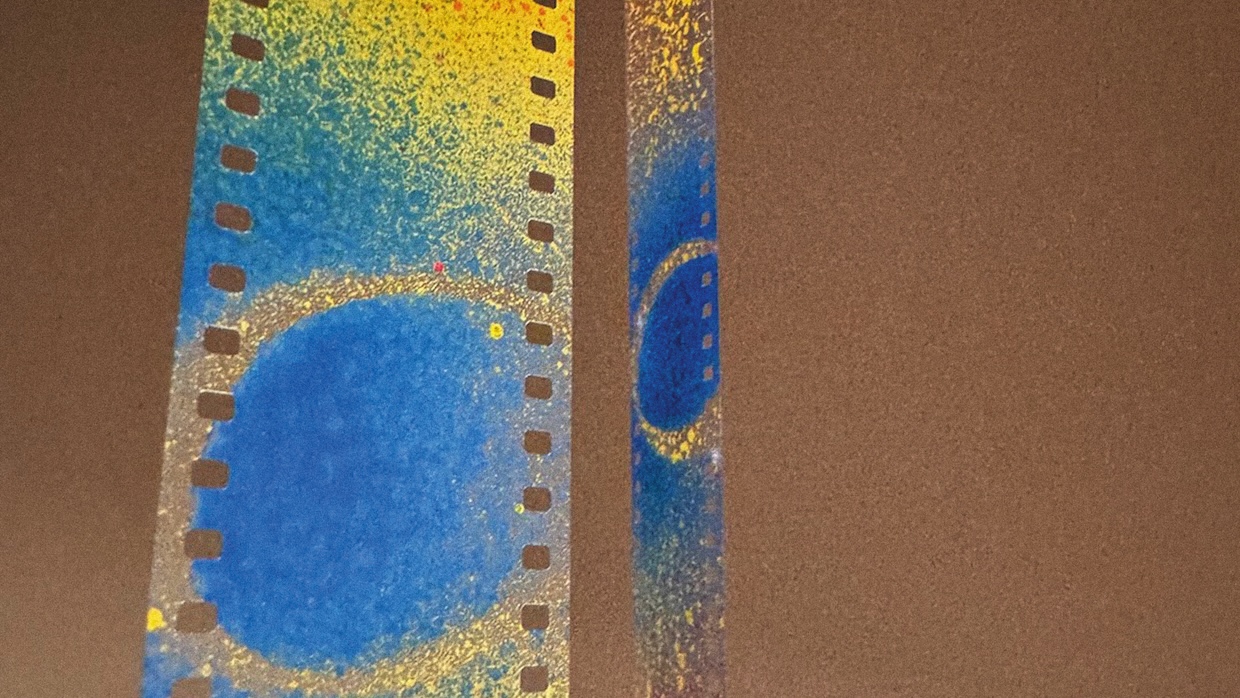

One of the handmade filmmaking techniques included spray-painting strips of 16mm clear leader and using various objects as stencils

One of the handmade filmmaking techniques included spray-painting strips of 16mm clear leader and using various objects as stencils On September 26, I flew from Los Angeles to Atlanta, then drove north toward Rabun Gap, eventually turning west on Bettys Creek Road to find the sprawling 600-acre campus of the Hambidge Center in the heavy rain preceding the arrival of Hurricane Helene. I had signed up for a workshop called “Cinema From Scratch: From Camera Obscura to Handmade Film,” with Brooklyn-based artists Luis Recoder and Sandra Gibson, and the urge to meet the pair, whose work with the materiality of cinema I’ve loved for two decades, overrode this Angeleno’s terror of foul weather. Carefully tracking what was being called a tropical cyclone with “pronounced and rapid intensification,” I figured there would be a few hours after touchdown before the storm hit. How bad could it be?

After being shown my room by Hambidge’s Mindy Chaffin, Sandra, Luis and I met in the main workshop space, called Bunnen Commons, in the Center’s Antinori Village, a cluster of recently built guest rooms. I was both flattered and quietly worried that I was the only workshop participant to show up, but my delight in meeting the artists and the beauty of the green, green woods overshadowed everything else. A neighbor, Craig, joined us, I think maybe so I wouldn’t feel so weird as the only student, and Luis and Sandra—both tall, lithe, intense—dove right into our topic, taking us back to Leonardo da Vinci, René Descartes and Johannes Kepler with an expansive visual presentation sketching the history of camera obscuras and their own work building them.

In the spring of 2013, for example, Sandra and Luis built a ten-foot-tall cylinder with a small hole in one side in Madison Square Park. Visitors could step inside and see an upside-down view of the Flatiron District and experience an image of the world outside. Delighted by the communal, immersive quality of their project, the pair continued to explore a full array of camera obscuras, some with multiple apertures, others with lenses borrowed from various devices. For example, with Obscurus Projectum, created at San Francisco’s Exploratorium two years later, Gibson and Recoder repurposed a theater, allowing a beam of light into the space from outside as a way of staging the earliest form of cinema. Shifting focus away from the room, this obscura attended to the quality of the light.

During their presentation, Sandra and Luis took turns describing the images and their projects, and at one point, Sandra said excitedly, “There are images everywhere!” I nodded in agreement: Sure, there are images everywhere. I didn’t really know what she meant, but it was time for dinner. We enjoyed well-seasoned grits ground nearby at Barker’s Creek Mill, and a brief safety overview followed: steer clear of wild hogs; bears are rarely seen but, again, stay away. Snakes, I silently wondered? Then, the storm details: Hurricane Helene was expected to arrive at 3:00 or 4:00 a.m. “The buildings are strong,” assured Jamie Badoud, Hambidge’s executive director. “But the bathroom is the strongest space.” Later, lying fully awake in bed, I pondered the safety of sleeping under the huge windows in my room. It was too dark to see the trees, and the wind was picking up as I finally fell asleep.

No trees crashed through the windows; no water from the nearby creeks overflowed into our rooms; no hogs or bears; no snakes. I woke to gray skies and intense quiet. The power was out, so we had no light, no running water and no internet. Luis and Sandra were undaunted, however, and we turned to our first task: turning room no. 7 into a camera obscura. We used black cinefoil and tape to cover all exposed glass in the room. Cutting a three-inch hole in the center of the foil blackening the window, Luis added an iris. Then, holding up a piece of semitransparent plexiglass, Sandra “caught” an image of the trees and cloudy sky outside. As she moved the transparent screen closer to the hole, the image softened into large green circles; pulling backward, the image from outside gradually, thrillingly resolved. Sandra continued to move the plexiglass around the room, “scooping” up images that were ready to be seen in the light. Suddenly, her comment from the previous day made sense. Images are everywhere!

News from the outside world came by way of neighbors. Trees had been blown down on both sides of Hambidge, blocking the road on either side. The storm had veered east, devastating parts of North Carolina, Tennessee and Virginia. It was sobering to hear the details, and later I sat quietly inside the camera obscura, marveling at the quality of the light while sensing the profoundly moving experience of reduction. These days, every torrential storm is a bleak, harrowing reminder of human hubris; the camera obscura signals a kind of divestiture, a back-to-basics gesture acknowledging the wonder of light that felt appropriate to the moment.

On Saturday, Sandra and Luis set aside their calm demeanor and pointed me from table to bucket to projector like drill sergeants. Stickers, bleach, washi tape, scotch tape, delamination, scraping, rubbing, painting, inking, hole-punching—we did it all. We made loops and watched the results instantly, and I was able to figure out a bunch of things that I’d read about but could never make work on my own. Things that sounded like way too much trouble—bleaching 16mm black leader to make a flicker film?—Sandra and Luis did quickly, casually and with their quiet flair.

As the day started to get dark, Luis fired up a generator on the porch outside, and I was the lucky recipient of an impromptu performance. Sandra and Luis demonstrated how a pair of films featuring lines scratched into the emulsion could become a spectacular display of light, shape, pattern and rhythm. With the projectors turned around, the beams illuminated the trees outside, creating a dancing weave of tree trunks and branches. I found myself on the porch in the wind, waving my arms in the projected light, remembering in a powerfully embodied way why I love film so much.

Sandra had explained earlier that, for her, projection performances are a way to make the work feel uniquely her own. While the animation techniques we’d explored could be created by anyone and therefore felt somewhat anonymous, the projection work feels more intimate and specific. For Luis, the camera obscuras and projection performances create an experience with other people that he relishes. They spark conversations and inquiry, and it is the communion with an audience that propels him.

At one point, while Luis was demonstrating various ways to thread and double-thread the projectors, one of the loops got caught, and the emulsion began to melt, the image dissolving in a bubbly, wavering puddle. I felt a moment of panic—do something!—but Sandra ambled over while Luis quietly coaxed the piece of blackening plastic forward so that the melting could continue. When I realized that this was not a moment for fear but rather wonder, we stood watching for several minutes as the film strip created its own performance. The smell of melting plastic mixed with that of gasoline from the generator. Combined with the quiet that comes after a storm, I felt a little woozy in the blend of beauty and destruction; the strangeness of our machines and rituals; the incredible kindness and generosity of these two artists; and the desire foundational to cinema, to see something more in the darkness.