Back to selection

Back to selection

TORONTO: JOHN LYDON IS IN A BAD MOOD

He’s hungover from partying after the premiere of the Norwegian coming-of-age drama, Sons Of Norway, here at the Toronto International Film Festival. My photographer Linda and I arrive at a stuffy, claustrophobic mezzanine at the posh Hazelton Hotel. The busy publicist warns us that Mr. Lydon is an “unpredictable” mood.

Great, though I shouldn’t be surprised. After all, John Lydon is Johnny Rotten, the surly singer of The Sex Pistols and the 56-year-old godfather of punk. That’s how he’s credited in this film in a cameo appearance near the end though he’s credited as executive producer under his birth name.

Journalists who stagger out of their interviews assure me that Lydon is in unusually fine spirits, pleasant and polite, even signing autographs. As I wait, I go over my questions about this film. Sons of Norway is based on screenwriter Nikolaj Frobenius’ life growing up in Norway as a young punk rocker as embodied by 14-year-old Nikolas (Åsmund Høeg) growing up with his free-spirited hippie parents until his mother (Sonja Richter) is killed in a traffic accident. The Pistols’ seminal album, Never Mind The Bollocks, fills a spiritual vacuum in the boy’s soul, and overnight he snips his long hair, spikes it and sniffs speed as he plays guitar in a punk band.

However, his eccentric dad (Sven Nordin) steals the focus of the film as he quits his architectural job, builds a homemade motorcycle for two, and takes the boy to a nudist camp. Problem is, Sons of Norway sets us up for a generational clash that never happens, and though it’s charming and funny in places, overall it lacks conflict and direction. Just what is this film saying? Director Jens Lien and Frobenius weren’t telling after their screening though they were overjoyed when they met Lydon at a Public Image Limited gig in London late last year and, after calls and emails, convinced him to appear in their film.

Disappointed.

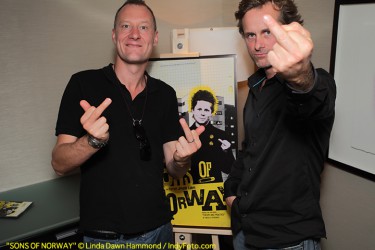

My photographer, Linda, asks if she can at least shoot Lydon. At least a photo. Publicist talks to Lydon and his manager and they give a green light. At least we have that.

Minutes later we’re ushered into a large, drab room, with cigarette smoke hanging like laundtry in the empty room, and meet Lydon. He’s actually smaller than I expected, but there’s no mistaking his persona, which fills the space in the room.

Linda shoots discreetly as a European journalist asks Lydon about the theme of the film. He answers: “It’s about humanity and growing up and teenage angst and rebellion and understanding your parents and your parents understanding you. All the good things in life that get pushed by the wayside. Most films are about nothing at all. This is about everything that matters to a human being.” (Kudos to the journo who let us eavesdrop.)

For someone who’s hungover, Lydon is clear, candid and to-the-point, like a fencer using his tongue as a sword. Problem is, he turns nasty when the journo asks him who he looked up to as a child. “Gandhi,” he answers, but says he didn’t wear a sheet and shave his head. When the journo asks him why not, the interview dies. Lydon says something about a “glib, asshole question” and kills this line of questioning. Dead.

I feel bad for the journalist who’s obviously thrown off, but soldiers on. Lydon’s manager waves us away. Time to go. We tiptoe out, but two minutes later, Lydon bounces past us to the elevator, presumably to grab a bite downstairs, since he hasn’t eaten all day. Maybe with higher blood sugar he’ll talk to me.

Twenty minutes later: no go. “Grim,” says the publicist. Should I stay or should I go?

I go, having done my almost-interview with John Lydon.

Punk isn’t dead. It’s middle-aged and cranky.