Back to selection

Back to selection

Richard Trank, It Is No Dream: The Life of Theodor Herzl

Studiously researched, It Is No Dream: The Life of Theodore Herzl reveals the life that informed Austro-Hungarian journalist-playwright Theodor Herzl’s creation of the Zionist Movement, which ultimately led to the founding of the state of Israel. Directed by Richard Trank, the film uses Herzl’s diaries and photographs, correspondence and drama, as well as a limited but effective pool of other historical artifacts to recreate the dynamic world of central European Jewry that Herzl sprang from, while explaining the rapid development of his politic cause in a way that will resonate with both laymen and history buffs alike. Narrated by Ben Kingsley, it features some dexterous voice work by Christoph Waltz, who inhabits the voice of Herzl’s writings.

A documentarian veteran, Trank is the longtime principal writer/producer/director at Moriah Films, which is the documentary production wing of the Simon Wiesenthal Center. Perhaps best known for producing the Academy Award-winning The Long Road Home (1997) under the Moriah Films banner, Trank has directed eight features, most recently Against the Tide (2009) and Winston Churchill: Walking With Destiny (2010). It Is No Dream: The Life of Theodore Herzl opens in Manhattan and Los Angeles tomorrow.

Filmmaker: How did your interest in Herzl’s life grow into this film? Given your work, it seems like a natural subject, but he has some inherent challenges as a subject that may have scared a number of other filmmakers off.

Trank: Well, at the Wiesenthal Center we produce a new documentary every year, year and a half. For many years, we were focusing on World War II, the Holocaust, the early years of Israel. We finished a film about a year and a half ago, almost two years ago, about Winston Churchill during the period in which he was the prime minister of England and was fighting Hitler alone, before the United States joined the war. Initially, when we started working on that film it was going to focus on Churchill and his relationship with the Jewish people, but then we decided it was going in a direction that was very parochial and we were very interested in this era when he was the prime minister waging war on his own.

Then as we were working on the earlier version of the film, I began thinking a lot about Zionism, Herzl and in how much of the Jewish Community Zionism has begun to connote something negative as opposed to something positive. So I wanted to explore that. I knew the basics about Herzl, but I didn’t really know about him. The more I learned about him, the more I was intrigued by this very unlikely person to begin a political movement that within a 50-year period led to the creation of a Jewish state.

Filmmaker: Journalists and artists are often revolutionaries, but rarely successful ones.

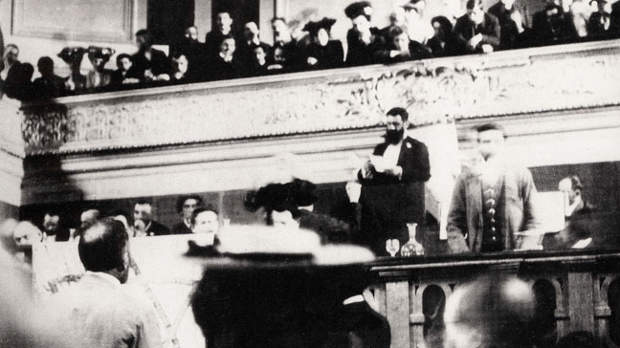

Trank: Zionism was a concept that had been around a long time. A small group of people had rallied around it, mostly poor religious people. There was something about the way in which Herzl articulated this idea and went about organizing it that brought it to life very quickly. Basically, within an eight- or nine-year period, he went from himself espousing something to this becoming a the largest political movement amongst Jews around the world. It was also his sense of theater and drama that he had in him as a playwright and a writer that led to it becoming a popular movement. When he put together the Zionism congress in Basel, in his head he was already organizing how the speeches would go and how people would be dressed and the pageantry, and that all came from his years in the theatre and actually writing the kind of theatre that had gone out of style in Europe. [The popularity of] writers like Ibsen and Strindberg, [who] represented a more naturalist approach to theatre, is what saw him become a failure in many ways as a playwright. [But] all of that pageantry worked very well with what he was trying to do.

Filmmaker: What are the limitations of making a documentary about someone like this, where there is some photographic historical record, but no footage? Obviously a lot of what you’ve done in the past revolved around World War II, where there is a substantial archive footage. How did you cope with those obvious restrictions?

Trank: This was kind of scary in a way because even with Herzl himself, you’re looking at twenty, twenty five photos. That includes his family, the Zionist Congress, all that. There is no film footage. One of the things I like to do is that even when I have a tremendous amount of stills and archival footage, I like to go to the places where things actually happened as they are now and then go back in time. So that we did all over Turkey, in Austria and Hungary, Germany, England, etc.

Then we were very fortunate because the Lumière brothers had just began filming the first ever images on film and what they were doing was they would go themselves or send another camera person and they would shoot the wonders of a certain city. Then in the Lumière cinemas you would go watch for a few minutes a place you would never be able to go to at the turn of the last century. The wonders of Paris, the wonders of London, the holy land of Constantinople, which of course today is Istanbul. We lucked out in that way because that was the exact period of time in which Herzl was operating and many of the places he was going to. So we were able to augment our very sparse photographic collection with this amazing footage that the Lumières shot as well as some of the footage that Edison’s company shot in the same period. It was a challenge that was a bit daunting at first, but we all got into it and it ultimately worked out well and we enjoyed it. I wouldn’t want to do it on every film, though.

Filmmaker: How did the sparcity of material effect the editing process? I imagine your choices were limited.

Trank: That’s interesting, because initially, and this is always the case, but I’ll overwrite certain things and the editor will be able to pick out where it isn’t working and we’ll be able to streamline certain things visually. In the case of Herzl’s story, the earlier drafts of the scripts I spent a lot more time dealing with his disappointments as a writer. What we found is that it started to drag. We had a certain amount of footage that we shot and a certain amount of period things we found that could work, but we were spending too much time and it wasn’t working. So that was an area where we found some ways the streamline it a bit. He traveled extensively and a lot of that started to become a bit exhausting, so we found a way to make that work to and yet still get across this idea that this was somebody who lived in an era when travel was very difficult and who was not in good health, but that he went from one end of Europe to another in a very concentrated period of time. I was a little worried when we working on the sequence early in the film about the Dreyfus affair, because I thought it was very important for us to get as much detail as possible and we were limited by what we had, but we were able to make it work. We shot in France and found some contemporaneous illustrations that really allowed us to tell the story.

Sometimes you’ll be at a screening and doing a Q&A and somebody will stand up who really knows the history and ask, “Well, why did you leave that out, or that out?” You have to say, “Well, it’s not a book and you’re limited in what you can do and you’re limited by time.” This particular film, we have more restrictions than we normally have because we didn’t have much archival footage or stills and there is only so much you can do shooting new footage and showing the interior of a theater or a stage or an empty seat without losing your audience.

Filmmaker: How did Ben Kingsley and Christoph Waltz get involved?

Trank: The Wiesenthal Center has had a long relationship with Ben Kingsley. In the late 80s, he was cast as Simon Wiesenthal in an HBO movie called Murderers Among Us, that was based on Simon’s book. He and Simon became very close. He loved Simon. After doing that film he said, “Anything you all want to do, please call on me.” So in the mid 90s, he narrated a few films we did, he then went on to narrate a couple other documentaries that we did, including our most recent film about Winston Churchill. We try to go to different people for different films, but there was something about the main narrative of this one that I thought would really work well with Ben’s voice. We approached him and he had just finished doing Hugo, so he was very well versed in the era and was very engrossed in the subject matter.

Then we were trying to figure out who we could get to read Herzl’s own words. I happened to be watching Inglourious Basterds and listening to [Christoph Waltz’s] voice; I know it’s an odd thing that he was playing an SS guy, but I like to go with unexpected choices for our narrators. This goes back to the mid 90s when, before he was ubiquitous, we had Morgan Freeman narrate The Long Road Home. So I thought Christoph Waltz would be a really interesting choice for this and we knew somebody who knew him. We got an email address for his manager and we heard back right away from him that he would be honored to do it. He had been working on Django Unchained for Quentin Tarantino and he fell off a horse and broke his pelvis!

This is shortly after he agreed to do this for us and we had heard he was in the hospital and we didn’t know what we were going to do because we figured he wouldn’t be able to do it from us. My producing partner was asked to speak at a panel at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences marking the 50th anniversary of Judgement at Nuremberg. Maximilian Schell and a number of the other actors who had been in the movie spoke on this panel. He circulated through the crowd after the event and I was in London taping Ben Kingsley. I get a call from Los Angeles and it’s Christoph Waltz. He had come to this event on crutches and had run into my partner. And he said, “I’m ready when you need me.” So I came back to L.A. and we recorded him. It was a wonderful experience. As it turns out, Christoph Waltz’s grandparents were actors in Vienna reportory company. It is very likely that they had acted in plays that Herzl had written. It is one of the many odd coincidences that cropped up on this project.