Back to selection

Back to selection

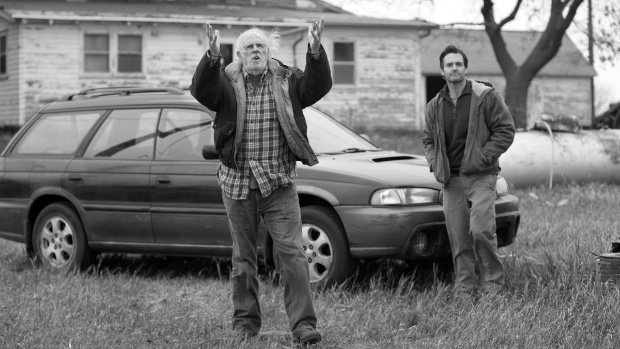

Nebraska Star Bruce Dern on Alexander Payne and “the Dernsies”

Nebraska

Nebraska This interview with Bruce Dern was originally published following the Cannes Film Festival, where Nebraska premiered.

If you ever have the good fortune of getting a press pass that grants you access to a roundtable with a Hollywood star, there are few actors out there who could provide a better interview than Bruce Dern, who recently won a Best Actor award at Cannes for his performance in Alexander Payne’s comedic drama, Nebraska. A planned 20-minute roundtable with a few grizzled journalists turned into a half-hour sprawling monologue of memories and observations on movie production, gently flavored with imitations of Hollywood luminaries ranging from Alfred Hitchcock to John Wayne, a reference to what he considered to be the most moving line he’d ever heard in a movie, and most engagingly, a thorough explanation of “Dernsies,” the often improvised touches that Dern habitually brings to (most) of his movies. He also talked at length about why he considered Alexander Payne to be a “genius” and why he “wouldn’t dare” to deviate from Payne’s script because “he’s too good.”

For Dern, the essence of acting entails getting at the reality of a character. When asked to define “Dernsies” — the term was coined by Dern’s friend and frequent collaborator, Jack Nicholson on Drive, He Said — he quickly launched into an initial definition, one that would be amplified and reworked throughout our conversation: “They are little things that you do, either character things or interjections of dialogue that are not on the page or behavior that is not on the page.” Then without pausing, Dern launched into what seemed at first to be a digression, an anecdote about why Alfred Hitchcock had cast him for Family Plot. But after spending ten (or 20) minutes with Dern, you quickly learn that comments that seem like asides are simply a means of getting to the point from a different angle.

Dern told us that when he’d asked Hitchcock why he cast him, the director replied, “In my office, I have 1,268 perfect frames on a billboard, but none of them are entertaining. I picked you because you’re entertaining, and you’re unpredictable, and that’s why you’re here.” And from there, Dern deepened his definition, explaining that “Dernsies” involve “unpredictable behavior that are part of the character that we feel might work just as good as what’s on the page already.” This is especially important when the film’s script is lacking or when the director is unwilling to take the time to “shoot behavior.”

This ability to capture behavior — the patience to just let the camera run — is what sets the great directors apart for Dern. For Dern, Alexander Payne has this skill. Describing a scene in Nebraska, in which Payne held the camera on Dern while characters were having a conversation in another room, Dern enthused that for Payne, “you don’t have to speak. He’ll leave the camera on you.” He added later that he knew he had connected with Payne after the first day of shooting and they shot a sequence at the police station that opens the film. He got a call from his daughter, Laura, who told him that she’d just gotten the most wonderful phone call from “a friend.” When Dern asked for more details, she said the call was from Payne and that he’d told her, “We have our movie.”

Almost as an aside, he discussed working with James Cromwell, telling us that he had uttered what he regarded as the most moving line he’d ever heard in a movie, but rather than follow that path, he looped back and began filling in even more descriptions of Dernsies, how they originated, and where the term came from. Many of his most memorable Dernsies came out of the low-budget and New Hollywood films where he got his start.

He recalled that he learned these skills when working on Roger Corman films in the 1970s: “We’d done nothing but Dernsies on the Roger Corman movies. You couldn’t stay alive if you didn’t invent stuff because there was nothing on the page. You had to do the film in nine days for a 108 grand — I mean 108 grand for the movie, not for us.” From there, he described the first time he used a Dernsie, in John Wayne’s The Cowboys, when he improvised with the film’s director, Mark Rydell, to have the Duke get shot in the back, explaining that until then, “He’d never been shot really, except by a sniper in Japan, and never in the back. Who shoots John Wayne in the back?”

These moments helped to convey Dern’s nostalgia for an older Hollywood model, one he saw as being more focused on craft than on stardom. He discussed his admiration of Elia Kazan, and especially for the sexually charged scene in On the Waterfront, in which Marlon Brando’s Terry Malloy picks up and briefly examines the glove dropped by Eva Marie Saint’s Edie Doyle: “Kazan, I don’t care what his politics were — the man had game. He knew how to see a movie before it began.”

Well over 20 minutes into our conversation, Dern was still going strong, reflecting on his wishes to work with Payne again and on his awareness that his assistant was “getting anxious” because the roundtables were at risk of getting behind schedule. Our lesson basically over, we thanked him for his time and then as an afterthought remembered that he’d never told us the movie line that had moved him so much. “Oh yeah,” he told us, it was a line from RKO-281, the historical film about the making of Citizen Kane, from James Cromwell, playing William Randolph Hearst: “There is nothing to understand. Only this: I am a man who could have been great, but was not.” For Dern, it seems, greatness — when it comes to directing and acting — comes from understanding human behavior and being patient enough to let it develop on-screen. Only a few filmmakers have the ability to do that. And, it appears, with Nebraska, that Alexander Payne is ready to join that pantheon.