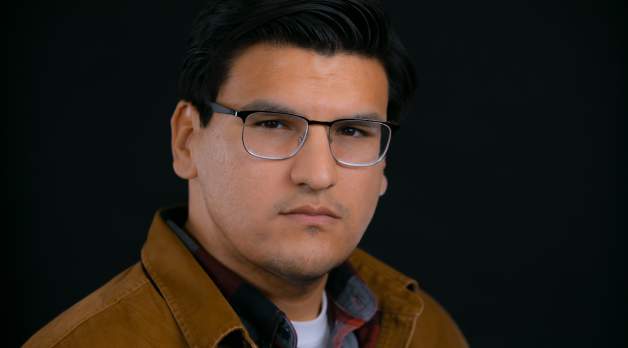

Lyle Mitchell Corbine, Jr.

Lyle Mitchell Corbine, Jr.

Lyle Mitchell Corbine, Jr.

There were several distinct phases in Lyle Mitchell Corbine, Jr.’s journey through cinephilia toward becoming a film director. As a preteen growing up on and around Native American reservations in Wisconsin and Minnesota, places where his parents worked (his dad is a casino executive, his mom a psychologist), he was into action movies and anything Schwarzenegger. Then, at 13, he saw Lost in Translation and “couldn’t stop thinking about it.” He says, “I realized that movies could be impactful in ways I never knew.”

Another revelation came at 17 when Corbine, Jr. — now a high school dropout working at his dad’s casino — saw Rushmore. “It woke something up in me. The kid in the movie was going through everything I went through — dropping out of school, being distracted by all the wrong things. After that movie, I went back to school — first community college and then University of Minnesota — and figured my life out.”

President of the university film club, Corbine, Jr. also started making films, directing a couple a year using DSLRs and local crews. “I went through a lot of different styles,” he says. “Zombie comedies, indie romcoms, people talking in a room pointing guns at each other — and then the arthouse versions of those as well.” After seven or eight years, only one of the 14 shorts had been accepted to a local festival, but meeting and connecting at the festival with actor Ajuawak Kapashesit led to a revelation: “I had never made anything dealing with my Native background. I could use prototypical Native imagery but do it through my own visual language, my own voice.”

The results are two striking shorts starring Kapashesit, Shinaab and Shinaab, Part II, both of which played TIFF and Sundance. They evince, perhaps, a Malickian vibe, with their somber voiceovers and fragmented, elliptical storytelling style, but Corbine, Jr. is mixing personal and Native history in hauntingly original ways. The former short captures the alienation of an Anishinaabe man who has left family and reservation for the city. The latter explores Ojibwe concepts of mortality through a son’s grief. With roving camerawork, eerie scores and sound work bridging the external and internal worlds, the films are structured, as Corbine, Jr. describes, like a series of diary entries speaking to the complexity of contemporary Native American identity.

Corbine, Jr. has attracted much support from independent film nonprofits, including Sundance, the Knight Foundation and Cinereach; the latter is behind his debut feature, Wild Indian, now in preproduction. The film begins in the past with Makwa, a 12-year-old Native boy, impulsively shooting and killing a classmate, then covering up the crime. Today, a reinvented Makwa is a San Francisco businessman whose guilt is a wound flimsily bandaged by professional success, material wealth and a new baby. Corbine, Jr. says the story began with his thinking about his father, who felt guilt over becoming successful after he left the reservation — an emotional theme given narrative backstory when Corbine, Jr. remembered an incident from his childhood involving the murder of a Native boy in his neighborhood. “I can write to those feelings,” the director realized. “It’s like a metaphorical version of the guilt you sometimes feel leaving the reservation because you did kill somebody; you became a completely different person than if you had stayed there. So, with every draft [Makwa] became more cold-hearted — not unforgiveable, because we understand his actions. But worse and worse.” — SM/Photo by Joel Feld

Contact:

Craig Kestel at WME