Back to selection

Back to selection

Disquiet

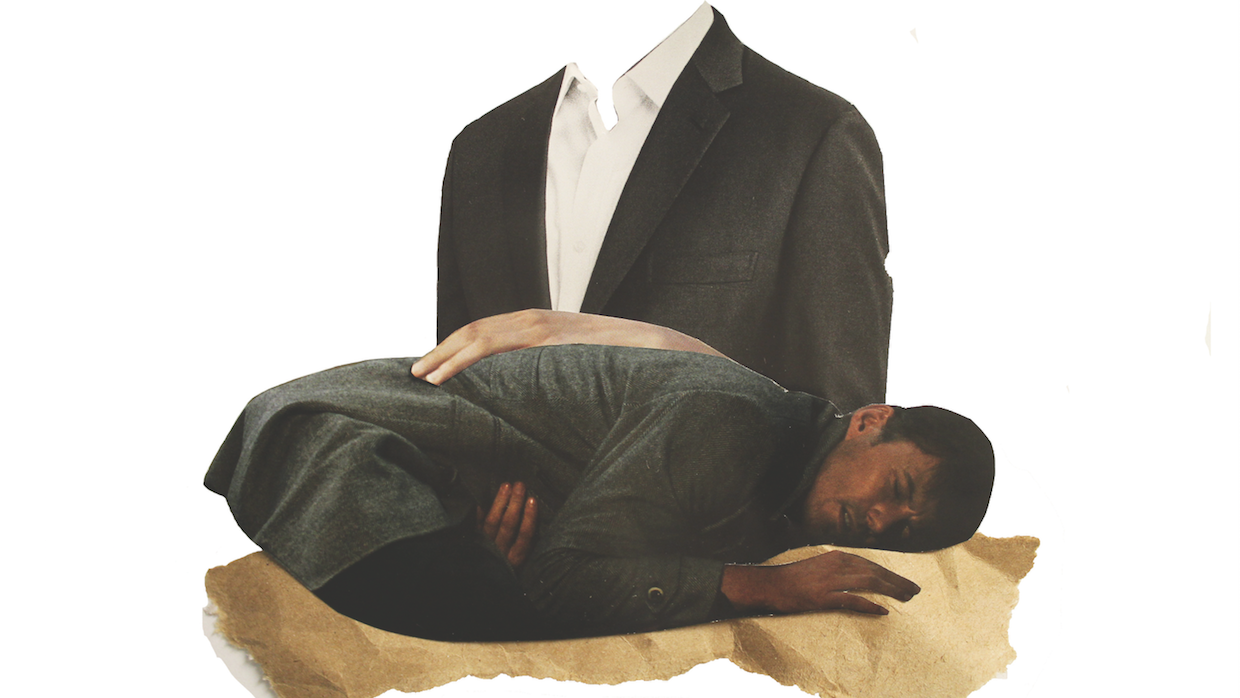

Image by Shayla Hayward-Lundy

Image by Shayla Hayward-Lundy “There’s an ambition that comes with wanting to work for Harvey Weinstein. Every day that I worked for The Weinstein Company I woke up with fear. You rationalize it as normal, that this is the dream we all want to be a part of; thinking you have to act a certain way, even though it’s an outdated way, an old way of doing business, but still how TWC operated. You begin to feel that hopeless, dreamless Hollywood factory. The culture was just so toxic. Everyone was scared, nervous, anxious, and now we’re confronting not only the sexual violence but the professional violence, a sort of violence that is baked into the texture of Hollywood. We said to each other this was not OK, and we knew it was not OK. We talked about it back then. We had conversations and then nothing happened.

“As the Harvey stories came out, I felt ill and sick. I’ve pushed the fear underneath since leaving, so I think as this has all come out, I’ve been feeling grief and sadness for the victims. A sense of loss, really.” — Joe Pirro, executive

As a contributing editor for Filmmaker Magazine, I write about women. I profile executives, distributors, managers and programmers in my column, Persona Project, and I interview mostly women directors from around the world at festivals. The intention when I first began this work was to seek out some of the sharpest people in the industry as they are rising up in their careers, charting them as they build influence and wield the potential power to enact actual change in this business, through hiring practices and green-lighting decisions.

I was desperate to surround myself with women, to cultivate female voices in writing, but also, I think, to build a subconscious force field. Interviews happen on and off the record, over cocktails at parties, on rooftops and beaches, in bathrooms, cars, empty theaters, hotel rooms. For years, I’ve felt that interviewing women is empowering. I’m realizing now that the main component to what has been empowering about these interviews is consistently feeling safe.

Something cracked open inside me as the Harvey Weinstein stories broke. The collective horror coupled with catharsis (or is it collective catharsis coupled with horror?) coursed through me, spilling over in texts, e-mails and endless conversation. Before fully grasping why, I had emailed about 60 men I know who work in film — queer, straight, white, not white, young, indie and established Hollywood men. I asked for volunteers willing to sit with me and share candidly about how they’re experiencing this moment in history, to listen to my questions and to pose others in return. Of the 30 men I ultimately interviewed, some are friends, ex-coworkers, current collaborators, festival comrades and relative strangers. Messy and exhaustive, the process has felt productive to me because of the range of perspectives and the variety of voices, male voices I’m now empowered to collect in order to begin the work of unspooling what’s gone unspoken. [Editor’s Note: these interviews were conducted in October and November, 2017, and this piece was first published in Filmmaker‘s Winter, 2018 issue.]

Dan Schoenbrun, producer: Where do I start? It’s a hard thing to talk about. I don’t think I, as a straight, white guy, should be the microphone or mouthpiece at the center of this moment. But at the same time, I feel like there’s a real responsibility. I feel like I shouldn’t worry about what I’m saying because I should use my privilege to speak out. I’ve tried to walk a line of not talking over people and creating space for others.

Paul W.R. Perez, producer: I heard about Weinstein being a creep, and I’m nobody. It’s mindboggling that it went on for so long. But at the same time, scarily, you could see how he could do it. I don’t think he’s a mastermind. It’s just power.

Jeff Stern, producer: I’m a bit fearful about speaking up in this environment where everyone wants to be heard and everyone wants to chime in because men need to listen right now. This is also shedding light on workplaces that foster professional violence and threatening behavior. This industry is just so offbeat. “You can handle this” becomes a point of pride, a way to fetishize abuse, justified by the idea that it’s about building character and a backbone. Bad behavior is sometimes enabled by virtue of working in this industry. There is no logic to why people behave badly. And now we’re all checking the receipts.

Noah Stahl, producer: It’s like if you lived near a nuclear power plant: You’d absorb toxic waste.

David Wain, director: I can’t believe this is happening. My ex-wife and others close to me have come forward as accusers. At least one of the accused is a friend of mine. This is all I’m thinking about. I’m trying to understand how I should navigate right now, as a white, male, single, divorced director who could potentially be in a position to hire anyone I cross paths with in Hollywood. I consider myself progressive, well-intentioned — a good person. A lot of my comedy has been about sex and crude stuff. I’m thinking about how one’s intentions are one thing, but awareness is the other part. Being the common sense nice guy is not so simple. I’m asking myself questions and thinking about them. I’m thinking about many relationships I’ve had with people I’ve worked with.

Anonymous festival programmer: I’m feeling the outcome of a lot of this. I was raised by a single mother, by a grandmother, and lived with two sisters. I was always just the guy. The dude. I never saw women as anything other than my equals. I was a geek up until high school, playing video games, and then I played baseball and sports and stuff. I don’t know where these groups of men are, whether certain men gravitate toward that behavior… I never did. I know there’s bad shit that’s happened in the music and film industry but not in front of me. If I saw this happen, that dude would be fucking gone. There’d be no coverup.

Kyle Ranson-Walsh, producer: I was on set the day after Ronan Farrow’s New Yorker piece dropped. Of course I wanted to talk about it. The reaction from the crew in the van was kind of dismissive. They had this “whatever, nothing is going to change” attitude, which really shocked me. I was thinking about the ramifications of the story because it exposes all of us. The next day, one of the crew walks in and makes a joke about how it’s fashionable now to admit to being abused by Harvey Weinstein, and I thought it was the most tone-deaf response. I was still trying to collect my words when another producer, a woman of color, called him out. I was so offended by the original comment, and then embarrassed that I didn’t speak up before she did. I appear to be a cis white dude; it is my responsibility to speak up.

Ashley Clark, programmer: The first thing that comes to mind is to look at things systemically, how power is handed down and how it manifests, even if thinking institutionally is difficult when it comes to a person’s behavior. Individual behavior and responsibility is a huge part of this, and every man has his own responsibility — to learn and to reflect on these recent revelations.

Brent Hoff, writer/director: I felt a horrible guilt initially seeing friends post things because it’s not conversations that have ever come up. Girls I’ve dated will say things like, “Men are pigs” but brush it off. But in the #metoo posts, women wrote out what actually happened. It was deep and dark and horrible. I blame myself for not pushing to learn these stories sooner from my close friends. Did they just not share them with me because it’s so common and normal?

Schoenbrun: I wasn’t surprised by the #metoo stories — surprise wasn’t a part of it. I think most men have a sense of how rampant this is in our industry and our culture. But the danger is how we treat it as an accepted social reality, even when we know it’s wrong. It sleeps in the back of our brain. To me, that’s more nefarious than ignorance.

Matt Porterfield, director: My dad used to promote this idea that men and women are different species. He used to say that American men have more in common with “Eskimo” men than they do with their own wives, which is absurd for many reasons. Yes, there are differences between the way men and women behave, but there are so many lines of connection that I believe in and want to promote. I don’t understand this idea of woman as the other and why we exaggerate the differences rather than the common human threads.

Michael Litwak, director: I’m thinking about the ways we’re brought into adulthood through community and learning customs from other people, older people, which contributes to the vicious cycle. We get information about how to deal with women from other men, and learn the cultural norms, like not being encouraged to cry or show emotion or cultivate deeper relationships. And then there’s this culture of sexual conquests, of one-upping one another. A lot of young men build their personalities around trying to please women, and they think women want them to be masculine, to be macho and make decisions, and not act gay. We learn performative masculinity.

Andrew Houchens, producer/festival organizer: I used to dread going to gym class as a kid, that locker-room environment. I joke around with gay friends about how much we dread the fist-bumping or high-fiving straight guy. That has always been so awkward for me. The L.A. bro-guys remind me of frat guys from college who were like, “Chicks, chicks, chicks. Let’s fuck.” That way men speak about women is not so much around me because I’m gay, I think. But it’s what comes to mind when I think of the LA world, the agent world: that it’s an extension of the fraternity culture, that masculinity where you’re only as powerful as the number of women you’ve slept with or the kinds of things you’ve been able to do to maintain your power.

Zach Stoltzfus, cinematographer: I’m not privy to locker-room talk. It dies if you don’t participate. That’s not to say it doesn’t happen. I’ve heard comments here and there, little things about “she’s really hot” or whatever, but those little things sit in the back of your consciousness and eventually accumulate, like gender-specific words that designate weakness: “You run like a girl.”

Jason Shrier, executive: I have a buddy who says “fag” all the time. I tell him to calm down and stop. Why does he do it? Insecurity? Ingrained behavior? We see this behavior in the workplace; people talking in such derogatory and abusive ways until it’s normalized. I should live in a way and behave in a way that speaks to how I think the next generation should behave.

Clark: Having grown up as a fan of soccer, I’ve seen so much boorish conduct in male groups. I’ve been privy to conversations and heard things that aren’t acceptable and haven’t stepped in. Our part to play is to listen and reflect and not perpetuate behavior, including more subtle microaggressions in the workplace. We have to be vigilant. The job’s not done just because some people are taken down. I see it as my responsibility to not repackage something a woman has said to me back to her in a booming voice.

Jonathan Hurwitz, writer: “Dialing in a joke on the penis phone” is when a woman pitches a joke and no one responds to it, but when a guy pitches the same joke, people love it. As a writer’s assistant, I’m used to letting everyone else speak first. I’m the youngest in the room and the only gay person. There’re such distinct hierarchies and a cone of silence—the idea that what happens in the writers’ room stays in the writers’ room, and that everything in the writers’ room is creative fodder.

Michael Gottwald, producer: Dudes talking about film like baseball stats is so male-film-culture specific. I don’t want to speak in absolutes, but there’s an obsessiveness to the way we talk about film and how protective we are over that.

Stahl: It has to do with control, establishing bona fides, sharing in the realm of knowledge.

Hoff: In a room full of guys at Sundance, the conversation is going to be different than a room full of men and women. I have seen men and women who can’t “hang,” either because they’re made uncomfortable by the douchiness or because they can’t play by those rules, but I don’t think tolerating toxic masculinity should be a requirement to be in the film scene.

Hersh: I don’t always feel this energy when I’m surrounded by straight, white men, but what I associate with it is a lack of empathy and a lack of eye contact.

Ranson-Wash: There are plenty of women who can “hang” on set. Any female DP can nerd out like the best of them. Nerd culture doesn’t have to be bro-y or hypermasculine. Think of the women at Comic Con. Women aren’t included because they’re overlooked and get talked over. I was 30 when I transitioned and had had a successful career as a woman in the business. All the behavior I learned how to do as a woman about how to take space in a meeting, I had to undo, now that I’m perceived to be a man. Does that make sense? As a woman, I taught myself to be louder, to assert myself more, to sit at the head of the table, but now that I’m a white man, I question whether I’m taking too much space. I’m always second-guessing myself, based on not wanting to be the dickish white guy in the room.

Porterfield: As human beings, we have to ask ourselves, to what extent and in what ways have we benefited from certain oppressive systems? As men, how do we benefit from patriarchy and privilege? I work outside Hollywood (which is its own unique monster), but as an industry, how do we contribute to the objectification of women, and how do we profit?

Litwak: After my first film went viral, I went to the Soho house in LA to meet with this manager who had a very successful company with lots of big clients. He asked me what’s my number: “How many girls have you slept with?” I told him it was none of his business, and then he said, “Well, I guarantee if you sign with me, I’ll double that number.” I told him I wasn’t interested in film for that reason, and then he course- corrected and re-pitched himself as someone who respects women. So I ordered an expensive steak and wasted his time. It would have sucked if he was my only option for management, but I was lucky enough to have other options and felt able to shut him down in that moment.

Schoenbrun: If you’re in a situation where there’s clear sexual assault, you think you’ll step in violently to end it. But what about casual sexism, the kind when you’re cringing inside at a social situation that’s clearly wrong but not quite physical assault? We find ourselves in those situations constantly. And it’s awkward to call someone out. That’s the reality of every social situation. You act differently around different people, which speaks to the definitions of power and integrity. It’s easy to go with the flow of culture that’s widely accepted. I think that that’s something I’ve grown more conscious of.

Hersh: I call people out. When people refer to 22-year-olds as “girls,” I’ll correct them and say “women.” When I hear someone talking about a woman in a way that’s objectifying, I’ll pretend like I’m agreeing with him in a jokey, overzealous way and repeat the comment back to him in order to implicate him. That’s my tactic. When someone is revealing to me that he’s kind of a dick or looks down on other people, I try to make that person a little uncomfortable. My theory is he’ll remember that feeling.

Stern: Speaking up has no relation to your job title, salary, your value as a producer or how good your taste is as an executive — it’s about who you are as a person. We should be creating a culture where people know their jobs won’t be in jeopardy for reporting abuse at all levels.

Matt Sobel, director: The truth is, we would like to believe that we’d do the right thing, that we’d come forward and do the right thing, but I don’t think we realize how much there is in all of us that doesn’t want to believe what’s right in front of us.

Anonymous director: To me, the behavior that’s getting called out is so obviously inappropriate. Grabbing someone’s ass or breast is just black-and-white wrong. Can you have a dinner because you want to get to know someone professionally? Of course. I have dinner with female collaborators all the time, and there’s nothing weird about that. Having a meal with another human being isn’t weird, unless you are a creep. Don’t invite an extra or a PA into your trailer if you’re a star. It’s just common sense.

Shrier: It’s been hard for me to find my bearings. We can’t throw away subtlety because we don’t feel that there’s safety. When you pull the curtain back, things aren’t so simple. On one side a lot of people say this is a witch hunt. Is Jeremy Piven an asshole? Is he a sexual assailant? I don’t know. A lot of people say it’s all bullshit. I keep hearing men say that this is ridiculous; this is destroying people’s lives. But if a couple of innocent dudes are thrown in the spotlight — if that’s the cost — so be it.

Clark: I’m hoping for a genuine institutional change rather than a cosmetic one, now that people are being held to a higher standard. From heinous cases of abuse to everyday cases of sexism, things metastasize. But I do think this behavior will be harder to form in the long run. People have to be big enough to look into smaller microaggressions, into low-level complicity in the workplace. You can’t have the worst abuses without them being stoked by smaller things.

Stahl: Thinking that this is the moment when everything changes is a fallacy. This is a moment of symbolic significance, but this industry is built on sexual predators and sexism and misogynist hierarchies. As indie filmmakers, there isn’t the same power grid as the Hollywood structure, but you have to awaken to how gender power dynamics are at play. The risk is patting yourself on the back and not doing anything day-in and day-out to change the culture in entertainment. You can feel good listening to a podcast that talks about these issues, but then there’s actually doing the work.

Sobel: Late at night, I’m thinking I’m a good person, but does anyone think I’ve been inappropriate? I have to ask myself: Are my hands clean? I hope most guys are thinking this, wondering who they might have affected. I’m thinking about moments in my past where I was confidently flirting with someone in a way that was maybe appropriate or inappropriate. Where’s the line? My girlfriend says the line is if I’m ever in a position where a girl’s response to a flirtatious event could affect whether or not I could do something for her professionally. I don’t ever want to be in that position. I feel weird even having people offer me coffee. I couldn’t imagine running a company and having underlings.

Porterfield: I’ve been at bars with people who make me uncomfortable because of ways they talk about women, about strangers, wives and younger people, too — “locker-room talk,” as Donald Trump calls it. And I’ve taken part in those conversations that I ideologically and fundamentally don’t believe in. I’m definitely guilty of walking away from a bad conversation with a woman in my life and thinking: “Bitch.” Men, myself included, objectify women, talk openly about women’s bodies and are complicit with this behavior in ways we aren’t even aware.

Shrier: Just because I’m not trying to get some in the workplace doesn’t mean I’m excused. You can turn around, look in the mirror and say, “What did I do wrong and how can I do it different?” My grandfather used to say, “I’d rather be wrong than a liar. I’d rather be a man of principle or not be a man at all.”

Schoenbrun: This is the hardest part. Getting white dudes to reflect critically when they have no motive to — because why would they? Everyone will think of himself as “one of the good guys” as he compares himself to someone else. There are classes of people all using their power to pressure women under them professionally or to pressure them sexually. But they’ll justify it to themselves. “I’m not a rapist.” “I don’t have to drug women.” And then there are those people who maybe don’t personally sexually harass women but remain silent as our colleagues and peers do. Those people are culpable, too. We all are.

Clark: One of the worst things any man can do is put himself above the fray, even if he feels he hasn’t done anything wrong with a capital W and says he isn’t implicated. Sexism is so heavily ingrained and loaded. The white-supremacist-capitalist-patriarchy, as bell hooks calls it, is very strong. It’s been resistant to many attacks over many years. This is maybe just the start of a change.

Hoff: What’s the answer at the bottom of this? Male dominance is ugly. Power and dominance is ugly, when wielded by anyone. We’ve all grown up in a world where it’s dog-eat-dog. Trump’s dad taught him that you’re either a winner or loser; no one will help you; you take what you can get. Our species will divide into these two groups — the parasites (those who take) and everyone else (those who want to work together socially). Here’s a question at the heart of humanity — is Harvey Weinstein, who has a completely parasitic approach to living on this planet and seems like a different species, fundamentally different from you and me?

Pirro: This is not about Hollywood. This is about the American workplace and the university system, and how we’ve implicitly and explicitly raised men to think they are dominant over women. As a white man, I recognize my experience is radically different from women’s experiences, so I want to listen and learn, which is what I think will contribute to radically changing the power structures. And I know I have to do something, but I don’t know what yet, other than to listen and be there to support the women coming forward.

Sobel: I feel at a loss for ways to positively affect the situation. Before recent events, I thought it was all of our responsibilities to at least not make the situation worse. Over the past year, though, I’ve come to believe that this is no longer enough. Now we all have a responsibility to move the needle in the right direction. One hopes there will be things we can be unified about, though as the “liberal elite,” it’s hard to unite on culpability. This notion of just listening and trying to empathize — sure, I do that, but that’s also a bit lame. Maybe there is a story for us to tell, and it’s a story about healthy ways of examining ourselves, clear-eyed ways, about how we’ve added to problems in ways we hadn’t realized. Maybe that’s what guys should be doing. We certainly shouldn’t be telling women what to be doing.

Shrier: Taylor, I think one of the big problems right now is that the conversations you are creating here are not happening. A lot of women in entertainment are sitting down with one another and sharing or having platforms online to share, and men are having similar discussions but on their own. Women and men need to talk like this, one on one.

Ranson-Walsh: Think about all the people who haven’t yet come forward. This must be very hard and painful for them. Every time someone opens the newspaper or Twitter, someone is triggered by their trauma. And what if you are somebody who’s made a mistake and you’ve worked hard to get over it? I’m all for calling people on their shit, but there’s got to be space for forgiveness. How do you hold people’s hands and hearts for pain and also for recovery? Social media is not good on gray. One-to-one, interpersonally, we can handle gray, but it’s hard to do that collectively. The worst outcome is that this hardens us even more.

Anonymous festival programmer: I’m thinking about how am I contributing by not doing enough. Am I not trying to do enough? I don’t know if I’m choosing not to see…. I think it’s easy to get blinded. There are dudes on the festival circuit who I know are a little handsy. People will tell me about something that happened, and I don’t know what to do. Do I say something? Do something? It’s put me in weird situations. I never look at those dudes the same.

Schoenbrun: What if there was actually a system of checks and balances in place to stop powerful men on film sets and in the film industry from abusing their power? It needs to be institutionalized. In most parts of the film industry there are still no HR departments, no formal sexual harassment policies. In the 1970s and ’80s in this country there was systemic regulation, checks and balances. Somehow that missed the entertainment industry almost entirely.

Ranson-Walsh: Part of what makes the entertainment industry so toxic is that lines are so blurry. The business runs on parties, which is how people make deals, meet collaborators, network — there’s this perfect storm, a fertile ground for misbehavior. And it’s not just sexual. It affects the formality or informality of professional relationships and friendships.

Wain: What does being single now mean? Having a “spark” with someone has a different, careful weight to it. I’m questioning myself all the time—“I’m not crossing

the line, right?” It’s complicated. What, if anything, is appropriate? Can I only flirt with someone who I could possibly never potentially hire? Or, do I only date outside show business, which in LA is an interesting proposition. One thing I know is that any dinner or drink that is — or could be — a date, I need to be ultra clear up front. This is one good thing about dating apps. If I meet someone on Bumble, there’s no ambiguity about why two people are meeting, right?

Ranson-Walsh: Desire is a real thing. The shitty thing that could come out of this is that we turn off our bodies and we turn off the way we energetically connect with people. There’s gotta be a way to deal with people sexually, and that energy, in a way that’s not fucked up.

Anonymous director: I’ve never had hookups on set. I’ve never been someone who has relationships with my actors during or after production. I never got that, that directors would have relationships with their actors or crew, because I always felt it would get complicated. How would you manage it? But set can feel like summer camp for crew and cast: isolated somewhere, making art, and one thing leads to another, and people hook up. You have to be careful in this environment about how you handle yourself — the days of willy-nilly making passes at people are over. And it’s more complicated when you’re in positions of power.

Pirro: This industry thrives on power. I think there’s something romantic about saying that change will come from a grassroots, ground-up movement, but I think that change will come from the top down. Leaders need to ask for feedback. What can we do to listen, to be open? These questions aren’t asked by people who are afraid to lose their power.

Porterfield: I believe in reparations, ideologically and politically: We have to pay it forward and put more women in leadership positions. I feel like there should be more quotas in the industry, supported by unions like SAG, grant organizations, and film commissions. SAG already has diversity initiatives, and that’s great, but productions should be rewarded for meeting certain hiring quotas to create more jobs for women and for people of color. There’re lots of jobs and lots of work to go around. We should share it more equally. Organizations that produce and support indie film could mandate that. They could put the systems in place.

Gottwald: In terms of changing culture, we’re just beginning to embrace female auteurs and new generations of them presiding over a female culture that’s exuding something new and different. This isn’t about female producers checking out in the men’s clubhouse. This is about women holding power to create their own power.

Hersh: What I envision is people working in an industry reflecting the demographics of the city or country they’re in. Seven percent of all films should be directed by black women because that’s seven percent of America. It’s not impressive to have that; it’s what it should be. I do think there are elements of change happening, but we have a long way to go. In fact, I won’t feel that anything is done until we can look back and see that 50% of all films ever made have been directed by women. Then I’ll know that we’ve gotten there.

Pirro: Looking back on my time at TWC, I’m thinking about what we did know and what we didn’t. It’s hard to pinpoint the level of detail in which we knew and what we surmised. It’s been a challenge to think about the ways we’re capable of deflecting what’s right in front of us. There are contradictions I haven’t yet worked out. There’s been a lot of group therapy between the people who have had hands in that company and know the culture of silence that persisted. We’ve found each other and talked candidly about our memories — less about specific stories and more just acknowledging that that was wrong, that was not normal, never was and never will be.