Back to selection

Back to selection

Lucy Walker, Blindsight

The projects Lucy Walker has chosen to take on in her career demonstrate an admirable desire to tell difficult and important stories. The British documentarian was born and raised in London, and during her childhood lost the sight in one of her eyes. However, if anything this only further fueled her fascination with film and other visual media. She was a literature major at Oxford University before winning a Fulbright Scholarship which took her to NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts, where she studied film. During this time, she made a handful of student films and a video for the Cowboy Junkies. (Walker is also a music fanatic who used to DJ as part of the Byzar ensemble, and produced IFC’s 2001 series on rock stars who act, Crossover.) After winning Daytime Emmy nominations in 2001 and 2002 for her directorial work on the children’s animated show Blue’s Clues, Walker had a breakthrough success with her first documentary feature, The Devil’s Playground, a highly acclaimed and revelatory film about Amish teenagers. After a successful film festival run, it played on TV and garnered Walker three further Emmy nods; it is now a hit DVD.

At the center of Walker’s new documentary, Blindsight, are two compelling characters: Connecticut native Erik Weihenmayer, the first blind man to ever reach the summit of Mount Everest, and Sabriye Tenberken, an intrepid blind German woman who founded the first blind school in Tibet — where the blind are treated as outcasts who people believe are being punished for sins of a past life. The film is the tale of Weihenmayer’s attempt to take Tenberken and six of her blind Tibetan students to the top of Lhakpa Ri, a peak next to Everest. Blindsight is not only a touching and beautifully shot movie about the exceptional courage and determination of its principal subjects, but also gives a fascinating insight into the contrasting ways in which different cultures deal with the perceived impediments of blindness.

Filmmaker spoke to Walker about her own partial blindness, shooting in the death zone, and being distraught when she couldn’t watch The Aristocats for a fifth day in a row.

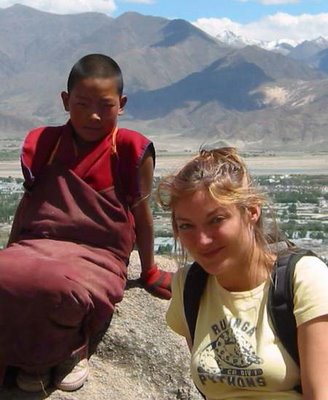

DIRECTOR LUCY WALKER WITH A TIBETAN MONK DURING THE FILMING OF BLINDSIGHT. COURTESY ROBSON ENTERTAINMENT.

DIRECTOR LUCY WALKER WITH A TIBETAN MONK DURING THE FILMING OF BLINDSIGHT. COURTESY ROBSON ENTERTAINMENT.Filmmaker: How did you first come across this story?

Walker: It came across me — I’m a lucky girl! Erik, who’s quite media savvy, decided this was maybe a movie. I was very lucky because they were asking around and they got a recommendation from Vanessa Arteaga, who I had worked with on The Devil’s Playground. In fact, a lot of people recommended me because after The Devil’s Playground I was the go-to person for getting young people who are generally inaccessible to open up. I also like these “crackpots only need apply” documentaries, these goose chases.

Filmmaker: You were also an apt choice because of your personal experiences with blindness.

Walker: I am blind in one eye, and had the sight in the other eye saved by doctors at Moorfield Eye Hospital in London. I’m sure this is partly why I’m such a cinephile, visual artist fanatic, photographer and painter, because when I was growing up I had these eye problems and everything visual became so precious and intriguing to me that I saw things with different eyes. I became fascinated with that whole world of optics. If I’d been born in Tibet, I would have been in a back room, like the kids were before [Sabriye] got there. So it was very close to home. It was very obvious to me immediately that we should start and end on darkness, a black screen. It was very intuitive for me. I felt like I’d done this sort of character-driven verité before, following people that I loved in these tender and very precious moments in their lives. I felt very privileged to do it and it was all a very good fit. I was lucky because it all happened really, really quickly: we were off to Tibet a month later.

Filmmaker: How did you prep for the movie?

Walker: I did everything – I didn’t do much sleeping. [laughs] That’s one way to put it. I learned Tibetan, as much as I could cram because I realized these kids’ English was not very good and you’ve got to try everything to connect with people. My Tibetan turned out to be ropey, obviously, [laughs] but it did turn out to be a wonderful way of proving to the kids that they would be better off speaking English. They were laughing at my Tibetan and then felt very comfortable trying out their English. We had these shoots in incredibly far-flung villages — sometimes we were driving for a week — and they’d certainly never seen Europeans or Westerners before, let alone a film crew, and I had enough Tibetan that in an emergency, with our limited time and limited resources, to run up to a nomad who was staring at us and said, “Hello, thank you. Could you please look over here not over here just for one minute, thank you very much” in my best Tibetan. He actually understood and we got the shot. I thought, “Crikey, that’s what I learned that Tibetan for!”

Filmmaker: Were you an experienced climber then, or was that something you had to pick up as you went along?

Walker: I’ve never climbed mountains before. I was very fit — I used to race in triathlons and marathons — but mountaineering was a whole new challenge. It was probably a good thing I didn’t know what I was in for. I had a funny time when I was buying equipment. This guy [in the store] was helping me and being a little dismissive, and then I got all this stuff and felt a bit bothered because the sleeping bag wasn’t all that warm and I kept thinking, “Why didn’t he give me a warmer sleeping bag? Crikey, I’m going up Everest!” So I went back to the shop and said, “I’m sorry but I really don’t have the right equipment.” They said, “But you’re going to 7,000 feet, right?” I said, “No, I’m going to 7,000 metres!” Then they looked at me and said “Oh God” and ran around the store throwing equipment and ropes and crampons at me. It was moments like that that it dawned on me the curiousness of what we were doing in mountaineering terms. The other thing was what cameras worked, what crew did we need; that was a gigantic set of decisions. Altitude does a lot: iPods, for example, stop working about 12,000 feet, so with electronic things you’re always in the land of guesswork. There was absolutely no margin for error because there were certainly no camera repair stores or places we could buy extra film or crew centers up Everest. You had to anticipate everything, and everything had to be “yak portable.”

Filmmaker: I think it’s an interesting choice that you made to completely absent yourself from the film.

Walker: I felt honestly that the story going on was absolutely fascinating and told itself. I also felt like eight main characters — plus the doctors and various other characters that come in and out — was such a challenge already to squash into a feature movie and were more interesting than me. There was interesting stuff that happened behind the scenes and actually our film crew doctor almost died. At moments like that, as a documentarian you feel torn because part of you feels a responsibility to the truth, and the truth of the expedition was that something happened that really haunts me and affected the way that I think of the trip when I think how close he was to being dead and how he was the healthiest of the lot. When something like that happens, you think “That’s not part of the official story and yet it happened,” and the line you’re always negotiating in a documentary is where does the observer become subject, and feeling out those ideas we all shook up in the 60s about truth and objectivity. But when you’re on a mountain and you’re all on the same rope team, there’s no such thing as objectivity.

Filmmaker: It must have been extremely challenging to be directing while on a perilous mountaineering trek.

Walker: It was like everyone had dropped acid, because you’d look around and think, “Who’s functioning normally?” and nobody is. Nobody is. For every 10 people who try to climb Mount Everest, one dies, and we were way up into the death zone. There’s a quote about Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers that whatever Fred was doing Ginger was doing backwards in high heels. I always felt like that: whatever was happening on the screen, it was happening to us too when we were having to make the film. My head was pounding, I honestly didn’t know if I was going to make it and I was expected to be doing all the verité filmmaker does, which is constantly evaluating what’s going on. You’ve got a big old group of rough and tumble activities going on strung out across a mountain when you can’t even take a step because you’re so oxygen-deprived, and you’re looking at your crew, because their lips are blue and the technical challenge of the cameramen was immense. It was just incredibly challenging stuff, but utterly exhilarating because as a filmmaker you know exactly when the moment is rich and fascinating and cinematic enough to really make this movie phenomenal.

Filmmaker: I read that you suffered a litany of injuries while making the film, including a broken leg, amoebic dysentery, giardiasis, headlice and altitude sickness.

Walker: Fortunately my leg was broken between the two trips [to Tibet] and I had taken my plaster off so it was simply painful. It took a while to heal after I got back because I probably shouldn’t have climbed Everest on a broken leg. That was painful. The thing that got me in the end was the amoebic dysentery. I became quite sick, but not until we were back in Lhasa and had everything in the can. One night when everyone was out at a party, the onscreen doctor Jeff left me alone with a drip and I had to, in my extremely delirious state, remove the [bag]. I was a complete mess and everyone was partying and it did cross my mind, for at least 30 seconds, to absolutely stitch him up in the movie!

Filmmaker: What matters more to you, that a film is successful, or that you’re happy with the finished product?

Walker: Success for me means the film being successful on its own terms, and Blindsight teaches us to question the definitions of success. [laughs] I feel like some films that neither succeed aesthetically or financially can be successes in people’s lives in other ways. If you had to put a gun to my head and ask would I make a film that I loved or a film that broke box office records and that I hated, I’d always say love over money every single time. But I also still have this naïve idea that wonderful work will find an audience eventually, somehow. With The Devil’s Playground, nobody expected anyone to see or like the film. We didn’t have a publicist, we didn’t have that “machine.” It was made without that hope that anybody in this town would see it, but I’ve gone to dinner parties in L.A. where every single person there had seen the movie.

Filmmaker: If you could travel back in time and be able to make movies in a time and place of your choice, where and when would it be?

Walker: I think right here, right now. I genuinely think that there’s an explosion of filmmaking energy right now, particularly in the nonfiction world, and I think this will be considered a golden era. There’s some phenomenal [documentary] work being done, and in fiction as well, and also in this whole beautiful space in between the two that people are playing with. I sometimes feel like it’s a little harder as a woman, that there are fewer opportunities and that it’s easier to overlook talented women. Sometimes I wonder if there’s going to be a gap in between me paying my dues — working my ass off in compromised situations for no cash and suffering lots of frustrations and disappointments and challenges — and, you know death? [laughs] I hope so. I feel like I’m still learning lots.

Filmmaker: What’s your favorite Bob Dylan album?

Walker: I’m thinking Blood on the Tracks, but I could change my mind in an instant. I guess it came to me at the right time and the right place. I have incredible memories of being a teenager with that album. I have always been a huge music nut, I’ve always been obsessed with records and cassettes. As a teenager before I had access to filmmaking equipment or could imagine that I could be a filmmaker I wanted to be a DJ. Most of my teenage memories have soundtracks firmly attached. [laughs]

Filmmaker: Finally, what was the first film you ever saw?

Walker: The Jungle Book. I had a broken leg when I saw it. I was in love with the movie as a kid, absolutely obsessed. I recall my dad carrying me into the movie theater and having to sit in the front row because I had a full-leg plaster. I didn’t even know where I was or what I was doing there, and then suddenly the lights went down and I had this experience. That was it. I grew up just before [my family got] VHS, so we had to go to the movie theater and I remember I would just nag everybody constantly to take me to the movies. There was one half-term holiday where The Aristocats, which I was obsessed with, was playing. I managed to persuade people to take me to see it four days in a row — my mum, my dad, my friend, my other friend — and after that I’d run out of people to take me to the movies and I was inconsolable. For the rest of my childhood, it was all about trying to persuade adults to take me to the cinema.