Back to selection

Back to selection

“POSITION AMONG THE STARS” DIRECTOR LEONARD RETEL HELMRICH

Position Among the Stars

Position Among the Stars

- Position Among the Stars

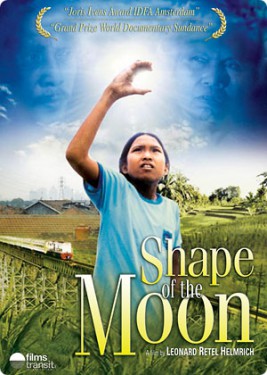

Winning both the IDFA (International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam) and Sundance for the same film isn’t anything new for director Leonard Retel Helmrich. Both Position Among the Stars (which received a Special Grand Jury Prize at Sundance this past Saturday) and Shape of the Moon — his previous documentary about three generations of the Shamsuddin family of inner city Jakarta — have won top awards at the festivals. These two documentaries, along with 2001’s Eye of the Day, combine as a trilogy to tell a moving story about religion, politics, and economics, all through the lens of a single family in present-day Indonesia.

The matriarch of the Shamsuddin family is Rumidjah, a strong-willed, feisty 71-year-old Christian in a family and nation of Muslims. She delights in taking her 8-year-old grandson to church and teaching him the Lord’s Prayer, if only to agitate her son. Rumidjah is a Puck-like figure, finding both entertainment and a tinge of sorrow when her daughter-in-law cooks her son’s prized fighting fish after an argument. Even though the grandmother seems to be grinning in the background of every domestic squabble, she’s also quick to put her home up for loan to finance her granddaughter’s college education (sadly, the disinterested teenager seems more interested in cameras, phones, and hanging out late with friends).

The film — shot using an unobtrusive, vérité style that Helmrich has labeled “Single Shot Cinema” — finds humanity in every character, and for all the exoticism of Indonesian culture, the film is instantly recognizable as first and foremost a story about family. The Shamuddin’s anxieties, hopes, and even their frequent — and occasionally hilarious — fights are fueled by nuanced, yet unconditional love.

FILMMAKER: Can you talk about your “Single Shot Cinema” style and how it benefits telling such an intimate story like Position Among the Stars?

HELMRICH: Single Shot Cinema is a technique of filming that enables you to shoot an event from the inside. You can do this by making use of camera movements to express your personal feeling about the event you are filming. The reason to move the camera should always be inside the frame. Therefore camera movements like panning between two points of interests are not done. Instead of panning you use orbital camera movements around a point of interest in order to change from one point of interest to the next in one flow. Doing so, the event will be filmed from your emotional point of view instead of your physical point of view. When this technique is used in a documentary and done by intuition, the camera movements feel natural. This is a huge benefit for telling intimate stories.

FILMMAKER: Can you discuss how you see Position Among the Stars fitting together with the two previous films you made with the Shamsuddin family? Will you stay with them for more films (a la the Seven Up series), or is this the final chapter?

HELMRICH: I see the three films, The Eye of the Day, Shape of the Moon and Position among the Stars as a kind of bridge. While Position Among the Stars has a rather strict narrative story line, Eye of the Day‘s story line is more open and poetic. Shape of the Moon is something in between these two. But the form reveals the content. When I started the trilogy twelve years ago during the time of the dictatorship of Suharto, the people in my film lived more day-by-day. While now in the new era of globalization my characters are more planning things ahead in order to survive. For the moment, Position among the Stars is the final chapter. I don’t know what the future will bring, but if it is interesting I’m always open to make a follow-up. Indonesia’s economy is a growing like most of the Asian countries. Who knows what will become of the girl Tari or the little boy Bagus in the near future?

FILMMAKER: Rumidjah, the matriarch of the Shamsuddin family, is really a fantastic character. She has a prankster element to her personality — like she enjoys creating a bit of chaos in her family to see how other member react (such as when she brings her grandson — who’s Muslim — to a Christian church). Can you talk about her dynamic with the rest of the family?

HELMRICH: Actually, Rumidjah wanted all her sons to have remained Christian. She has had many discussions about it as you can also see in The Eye of the Day and Shape of the Moon, but she always lost those arguments. From this underdog position, she still tries to impose the little power she has on the next generation — her grandchildren — by trying to make them Christian. But when this escalates into a discussion with her sons, she doesn’t want to fight it because she knows she will lose. That’s why she pretends that it’s a minor thing when her son Dwi starts arguing with her.

FILMMAKER: The scene where Sri cooks Bakti’s prized fighting fish to make him angry — and then Bakti’s reaction — is devastating. Can you talk about this moment in the film, how you saw it developing, and how you managed to let it evolve without getting in the way of it?

HELMRICH: We shot this scene with two cameras. After I filmed Bakti using Sri’s holy water and the quarrel about it, my camera tape ran out, so I went to my office one block away from the location. Meanwhile, my co-cameraman Ismail (Ezter) kept on shooting using the second camera. He filmed Sri, who was still angry about her husband’s behavior. When I was in my office Ezter called me to say that Sri had fried Bakti’s fish and that Rumidjah was going to tell Bakti about it. So I ran out my office to the place where Bakti was in order to film the arrival of Rumidjah. Knowing that some emotional moments were about to happen, I made sure that the camera would focus on Bakti’s face all the time.

FILMMAKER: The film hints at the rise of a much more extremist type of Islam in Indonesia. How prevalent did that feel?

HELMRICH: The Indonesian interpretation of the Islam has always been very moderate, free and open. But I noticed that the more fundamentalist Islam is now becoming more a part of the infrastructure in Indonesia. Like in many villages in Java, it is difficult to get the permission from the authorities to perform traditional wayang puppet play (shadow play) or traditional Javanese dances because it’s not Islamic. It’s not forbidden by law, but for any performance on a stage, you need a permit from a local official. And because this local official is afraid to do anything that could upset the local kyai or ustad (Muslim leader) he just doesn’t give permission.

FILMMAKER: How contentious was the Christian/Islamic split within the Shamsuddin family? Do many families in Jakarta have similar religious divisions?

HELMRICH: Having family members with different religious opinions has never been any problem in Indonesia. My grandfather who was a kyai never saw it as a problem when his daughter (my mother) married my Catholic father in the ’40s and had converted from Islam to Catholicism. He knew that the content of the Koran and the Bible was almost the same. The same stories, just a different interpretation. This was a common liberal attitude in Indonesia. But nowadays in Indonesia, it is rather difficult and even sometimes dangerous to openly convert from Islam into any other religion. You can get outlawed by certain fundamentalist Islamic groups who regard you a deserter.

FILMMAKER: You’re able to disappear into the film so well — the family seems to let you be present for everything. Can you imagine making a documentary any other way (which is to say, more stylized)?

HELMRICH: When making a documentary I would never use any other method of filming than Single Shot Cinema because I’m filming the reality that is unfolding in front of my camera. This way I can react to and anticipate the moments that are happening.

FILMMAKER: When the family is hiding possessions as they prepare to have their home examined by welfare officers, was there any expectation of you? Which is to say, did they want you to help hide things, did they tell you to stay silent, or was it really just as though you weren’t even there?

HELMRICH: It was a very stressful situation and Bakti knew perfectly well what items to hide and what not to while I didn’t. And I think that if I would have tried to help them I would have blocked his way too much so I decided to observe them by filming them. My main concern was that the welfare officer would see me with the camera inside the house. So I snuck out of the house from the back door while Ezter, my co-cameraman, filmed their arrival at the house.

FILMMAKER: Tari comes across as a bit spoiled and ungrateful — even as her grandmother is pawning her home so she can pay for college (which is a very moving scene). Do you see this behavior as simply emblematic of the younger generation?

HELMRICH: Yes, definitely emblematic. It’s an attitude I see among the younger generation all over the world. One of Tari’s friends told me even that she got fed up by hearing that they have to plan their future well. That the current and former generations have misused the earth’s resources that lead up to global warming. Now her generation has to deal with this in the near future. She said, “Let us enjoy and go down the drain all together.” Let’s hope this is just a temporary attitude of teenagers.

FILMMAKER: The film really does focus in many ways on possessions — Tari’s phone, Bakti’s fighting fish, Sri’s cooking utenstils, the video game system Bagus plays — and you draw such a stark, moving contrast at the end of the film when Rumidah visits Tumisah, an old friend who seems to have absolutely no interest in technology and is content collecting wood for fire and eating a simple meal of rice. The film almost seems to align and come into focus at that point.

HELMRICH: It’s true. Possessions are, and always has been a big issue of conflict throughout the history of mankind. And we were really surprised that this old lady in the countryside who never went to school had such deep thoughts about it. She understands that the less we rely on possessions the happier we can be.

FILMMAKER: Where do you see the intersection of a rampant materialism amongst the young in Indonesia along with a rise in religious extremism leading to in the future?

HELMRICH: The rise in religious extremism is actually a reaction to globalization and western economic influence. But nowadays you see that the popularity of Islam goes hand in hand with commercialization. For instance, in shopping malls you can often see fashion shows of the most fashionable veils.

FILMMAKER: Does the Shamsuddin family see themselves as “poor”?

HELMRICH: The neighborhood of the Shamsuddin family grew from being a slum into a working class neighborhood during the last ten years. When you look at the first films — The Eye of the Day and Shape of the Moon — you can see the development. Most Indonesian people live like the Shamsuddin family, so in that sense they aren’t poor, but a kind of middle class by Indonesian standards.

HELMRICH: The neighborhood of the Shamsuddin family grew from being a slum into a working class neighborhood during the last ten years. When you look at the first films — The Eye of the Day and Shape of the Moon — you can see the development. Most Indonesian people live like the Shamsuddin family, so in that sense they aren’t poor, but a kind of middle class by Indonesian standards.

FILMMAKER: How big of a problem does gambling (and gambling addiction) seem to be in Indonesian culture?

HELMRICH: Like in many Asian countries, gambling is a big thing and even a part of the culture. In richer families you find a phenomenon called “Arisan Keluarga,” which is a regular social family gathering. In order to find a reason to come together, they organize family lotteries where you can win a certain amount of money.

FILMMAKER: Did Bakti and Sri behave much differently as a married couple off camera? More or less affectionate? In your way of making films, is there an “off camera”?

HELMRICH: Bakti and Sri behave exactly the same when I’m shooting and when I’m not. It’s because of this fact that I decided to have them as my main characters.

FILMMAKER: When you tell the story of the Shamsuddin family do you feel you’re telling a story that’s emblematic of many current Indonesians — and perhaps more generally, a story about modern life everywhere? Honestly, the issues of rising religious extremism as well as materialism could easily be defining issues in a story about an American family.

HELMRICH: I think that story of the Shamsuddin family is emblematic of Indonesia as a country. The problems the country is dealing with are reflected and affects the lives of these people in this one family. And if you say that this story could easily be story about an American family dealing with a rising religious extremism as well as materialism, than this story is even more important to be told — because then it reveals the current situation of all cultures.

FILMMAKER: Being Dutch — with parents who were born in Indonesia – must have helped in so many ways to get trust and access, both within the family and Indonesian culture. Do you think you could have had that type of access otherwise? Could you imagine having equal access in Indonesia if you were American?

HELMRICH: I do think that my Dutch/Indonesian background has helped me understand the Indonesian culture and also understand the viewpoint of a Western audience. But as for the access, I think that anyone could have done that. It’s just a mindset. As long as you are honest to yourself and to the people you are filming you will get accepted by any society.

FILMMAKER: Do you already know some of the other stories you’d like to tell as a filmmaker?

HELMRICH: I’m working on some projects on the moment, but I don’t know yet which one will get financed.

FILMMAKER: How do you think documentary filmmaking can grow and evolve in the 21st century?

HELMRICH: Of course I can’t predict the future. But I can just express my hope for the future. I hope that documentaries of real life situations, the so-called cinéma vérité (Direct Cinema) kind of documentaries will gradually take over the man-made stories, the so-called “fiction films.” I hope that the audience in the near future will want to understand other cultures and these observational documentaries can contribute to that by providing a window.

FILMMAKER: What are some of the films you’ve seen recently, or in the past year, that that have really excited or moved you?

HELMRICH: In the past year I haven’t seen many films because when I’m working on my own film I don’t want to be influenced too much by other people’s work. But now that the film is finished I have a lot to catch up on.