Back to selection

Back to selection

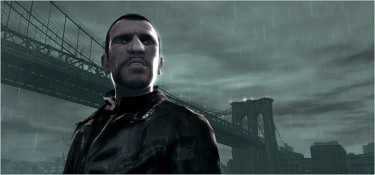

GRAND THEFT AUTO’S COCAINE NIGHTS

A misapprehension among people who do not play videogames is that the people who play them do so because these games must be fun. I am not saying that videogames are not fun. Sometimes they are and sometimes they are not, and whether one would call a game “fun” often has little bearing on whether or not one keeps playing it. To say that you play games because you are looking for fun is like saying you are hopping online or checking your iPhone because you are seeking information. You are, of course, but it’s way more complicated than that.

A misapprehension among people who do not play videogames is that the people who play them do so because these games must be fun. I am not saying that videogames are not fun. Sometimes they are and sometimes they are not, and whether one would call a game “fun” often has little bearing on whether or not one keeps playing it. To say that you play games because you are looking for fun is like saying you are hopping online or checking your iPhone because you are seeking information. You are, of course, but it’s way more complicated than that.

Tom Bissell’s article in The Guardian about his four-year love of Grand Theft Auto 4 and his intertwined cocaine addiction is one of the best articles I’ve ever read about video games. And that’s because it’s not ultimately about video games but about the qualities of filmed entertainment versus interactive play, about how we understand character (including our own), about self-actualization and self-defeat, and about violence and morals and the world we live in and the worlds we create. It’s not just a story of time wasted (Bissell’s productivity as a writer plummets during these years) and the neural rewiring power of interactive media — although it is also about these things — but a story of personal and societal change.

Read this great section:

While the GTA IV load screen appeared on my television screen, my friend chopped up a dozen lines, reminded me of basic snorting protocol and handed me the straw. I hesitated before taking the tiny hollow sceptre, but not for too long. Know this: I was not someone whose life had been marked by the meticulous collection of bad habits. I chewed tobacco, regularly drank about 10 Diet Cokes a day, and liked marijuana. Beyond that, my greatest vice was probably reading poetry for pleasure. The coke sailed up my nasal passage, leaving behind the delicious smell of a hot leather car seat on the way back from the beach. My previous coke experience had made feeling good an emergency, but this was something else, softer and almost relaxing. This coke, my friend told me, had not been “stepped on” with any amphetamine, and I pretended to know what that meant. I felt as intensely focused as a diamond-cutting laser; Grand Theft Auto IV was ready to go. My friend and I played it for the next 30 hours straight.

Many children who want to believe their tastes are adult will bravely try coffee, find it to be undeniably awful, but recognise something that could one day, conceivably, be enjoyed. Once our tastes as adults are fully developed, it is easy to forget the effort that went into them. Adult taste can be demanding work – so hard, in fact, that some of us, when we become adults, selectively take up a few childish things, as though in defeated acknowledgment that adult taste, with its many bewilderments, is frequently more trouble than it is worth. Few games have more to tell us about this adult retreat into childishness than the Grand Theft Auto series.

I am playing GTA4 right now. Like Bissell, I bailed halfway through GTA San Andreas because I was bored driving huge distances to restart failed missions in the second world. I’ve probably only played it in a single stretch about a tenth as long as Bissell did in that 30 hour marathon. (I am also not doing cocaine.) I can’t say I am as hardwired into the psychology of Niko Bellic as Bissell is, although I will say that I felt a sense of accomplishment this past weekend as I succeeded in finishing the difficult mission of killing three union foreman at the construction site. And I would be lying if I said that after playing the first world and unlocking the game’s version of Manhattan I wasn’t disappointed that GTA’s mapping wouldn’t let me drive by my apartment.

I hesitate to quote more because if you are interested in these things you need to read the piece, but here are two great paragraphs from near the end:

Video games and cocaine feed on my impulsiveness, reinforce my love of solitude and make me feel good and bad in equal measure. The crucial difference is that I believe in what video games want to give me, while the bequest of cocaine is one I loathe. I do know that video games have enriched my life. Of that I have no doubt. They have also done damage to my life. Of that I have no doubt. I let this happen, of course; I even helped the process along. As for cocaine, it has been a long time since I last did it, but not as long as I would like.

What have games given me? Experiences. Not surrogate experiences, but actual experiences, many of which are as important to me as any real memories. Once I wanted games to show me things I could not see in any other medium. Then I wanted games to tell me a story in a way no other medium can. Then I wanted games to redeem something absent in myself. Then I wanted a game experience that pointed not toward but at something. Playing GTA IV on coke for weeks and then months at a time, I learned that maybe all a game can do is point at the person who is playing it, and maybe this has to be enough.