Back to selection

Back to selection

The Internet and the Cult Film: On A Fan’s Notes

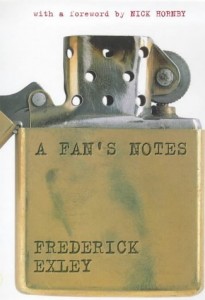

A Fan's Notes

A Fan's Notes I stopped collecting comic books years ago, and I was never much of a vinyl person. Do you know anyone who truly fetishizes out-of-print books, because I don’t. Who needs rare DVDs anyway? Not suckers with Netflix streaming or HuluPlus accounts. The DVD has only been around 17, 18 years — what could possibly count as rare, even? Is there such a thing?

Perhaps that DVD of an oddly artful B horror film from the ’70s that went out of print in 1996 and has never returned, but piracy has gotten so advanced now, surely you can find a stream of that same film, made from one of those DVDs you so covet, if you know where to look. Just demand: let me watch this (hint, hint).

I haven’t watched a VHS tape in nearly four years. I’ll blink and it’ll be ten.

You see, for this humble author it’s always been the truly long lost films, the ones that got away from the culture in a big, bold, utterly forgotten way, neglected by the studio, mishandled by the archivist, bombed by the Nazis — these are the things that still make me most excited to go to a festival, or a rep house or someone’s basement who just happens to be clicking on a rogue URL, beamed into their flatscreen, which will deliver a tiny sliver of forgotten cinema to us.

There are films, often adaptations of big mid-century novels, often little seen cult items from countries that hardly exist anymore, which I’ll spend inordinate amounts of time Googling, often in the middle of the night, for no discernible reason other than my obsession and insomnia. Chester Himes’ titanic 1946 negro protest novel If He Hollers, Let Him Go, made into an apparently forgettable 1968 movie with Lawrence St. Jacques, is one of these. I once saw a still from it in an academic text written in the ’70s; at this late date in history, it’s probable that I alone long to see it. I likely never will.

So it was too with A Fan’s Notes. Directed by Eric Till, a Brit who, other than 2003’s Martin Luther biopic, has spent much of the past 40 years directing TV movies, A Fan’s Notes is an adaptation of Frederick Exley’s beautiful and damning autobiographical novel. Financed and distributed by Warner Brothers, it was never popular and slunk, despite its 1972 Cannes competition slot world premiere, into the peculiar hole of never-on-home-video obscurity. I routinely tell people who are as enamored with the novel as I that a film adaptation exists. They uniformly look at me in confusion. No more.

At last I saw A Fan’s Notes, object of my peculiar, cultish obsession, and I saw it on YouTube. I paid WarnerVOD (or some combination of Warners and Google) $1.99 for the privilege. The stream looked pristine and it had clearly been struck straight from a print; it contains cigarette burns where the reel changes were. And very soon the allure was gone, but we’ll get to that in a second.

No one should have had a life like Exley’s, consumed as he was with his own status anxiety (one he dealt with mostly with booze and tobacco), but on some level we can all be glad he did. His is a painful and painfully funny book. Through Exley’s earnest account of his own descent into madness, his indulgences in football obsession, lonely womanizing and failed monogamy, A Fan’s Notes, which knows not whether it wants to be a memoir or a novel, teaches us a lot about what it meant to come of age as an ambitious, would-be intellectual, or just a drunken young man putting on airs, in the 1950s, at that precise post-war moment when the country first began to lose its fucking mind. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Exley — institutionalized when he began the book just as his namesake protagonist is — never could duplicate it. He sunk back into drink and envy, before dropping dead of a stroke at 62, having published two lesser heralded books.

No one should have had a life like Exley’s, consumed as he was with his own status anxiety (one he dealt with mostly with booze and tobacco), but on some level we can all be glad he did. His is a painful and painfully funny book. Through Exley’s earnest account of his own descent into madness, his indulgences in football obsession, lonely womanizing and failed monogamy, A Fan’s Notes, which knows not whether it wants to be a memoir or a novel, teaches us a lot about what it meant to come of age as an ambitious, would-be intellectual, or just a drunken young man putting on airs, in the 1950s, at that precise post-war moment when the country first began to lose its fucking mind. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Exley — institutionalized when he began the book just as his namesake protagonist is — never could duplicate it. He sunk back into drink and envy, before dropping dead of a stroke at 62, having published two lesser heralded books.

A Fan’s Notes the novel/memoir hybrid is a one-of-a-kind marvel, a zeitgeist-y treasure. Sadly, A Fan’s Notes the movie is not a very good one, although it’s bad in an interesting way; there are hints in its madcap tone, in Jerry Orbach’s often effective, wide-eyed, hyperactive performance, in the shifty, almost ’90s-Egoyan-like editing, drifting back and forward in time between the heady days of Exley’s New York post-collegiate life and his days in the loony bin, that create a texture capturing the ribald humor and heartbreaking melancholy of the book.

This author is sad to report, however, that Till’s film is too reliant on cheap montage, too unwilling to plumb the book’s most bitter depths, to properly satisfy one’s expectations. It is a deeply unsure work, gifted with amazing material, not sure within its own constraints what to do with it. From the music supervision to the photography, it seems mired in a willful mediocrity, confined to choices that aren’t especially bold or particularly interesting, even as its cadences (it contains some extraordinarily long scenes, and not particularly boring ones) and editing rhythms seem of a piece with the type of film that could capture the novel’s core themes. Indeed, its ambitions are in the right place. It’s no simple task to dramatize a man’s desperation and lightness, his resignation of selfhood in the thrill of vicarious accomplishment, when watching more physically gifted men achieve glory and infamy playing a game you once aspired to at such a high level. Till’s A Fan’s Notes ultimately fails to capture the meaning of Exley’s Giants fandom, at least as described in passages like this:

“Why did football bring me so to life? I can’t say precisely. Part of it was my feeling that football was an island of directness in a world of circumspection. In football a man was asked to do a difficult and brutal job, and he either did it or got out. There was nothing rhetorical or vague about it…. It smacked of something old, something traditional, something unclouded by legerdemain and subterfuge.”

More damaging, the movie shies away from the most painful aspects of Exley’s mental ward incarceration. Insulin shock and electroconvulsive therapy are hardly touched here, and the film, had it found a wider audience, would have surely lived in the shadow of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.

The film retains the lugubriousness and non-linearity of the audacious book from which it came; this was probably unwise. While it serves to solidify the art-film conventions which likely prodded the Cannes committee to include it in its 1972 selection, it also makes Exley’s journey seem somehow less full, more scattershot. The movie chooses to ignore Exley’s years of willfully sitting on his mother’s couch, both before and after his mental infirmity, as well as Exley’s time at USC, passages which contain some of the novel’s most humourous moments, when he somewhat rebelliously for an East Coast WASP consorted with blacks and gays. Likewise, his time as a pre-Mad Men PR hack, in which he witnesses the absurdity of the burgeoning American way of consumerism, is only barely glimpsed. His father’s fatalistic semi-pro football stardom and cancer death are also glossed over in barely felt montage. The central obsession with Frank Gifford, who is credited as playing himself although he only surfaces in game footage (he is actually quite a fan of the novel), is frequently referenced, but rarely felt.

There is always something somber in finding cult items like this available in some wholly inglorious way; the allure of their separateness from the rest of cinema is broken and almost never returns. Would I have liked A Fan’s Notes more had I glimpsed it once, in a place where it would never play again? Perhaps. It’s hard to say.

If the cult film is a dead thing in the era of instant availability, when only the digital aggregators make any money in the business of cultural reproduction, I’d almost rather encounter A Fan’s Notes like I did another, far superior movie languishing in the Warner Brothers Archive, one that is not available in their new made-to-order DVD, thankless “plop it up on VOD and see if it sticks” scheme. That movie, Bill Gunn’s “should be legendary if only it was seen more” feature debut, Stop!, may surface on home video one day soon. Yet the sensation I had on a Sunday afternoon three years ago, when ex-BAM programmer Jake Perlin had the courage to screen it for free on bootleg VHS acquired through sundry, near magical means, assuring us we’d likely never see it again, was one I’ll never replicate. The internet giveth, and it taketh away.