Back to selection

Back to selection

SXSW: Five Questions for The Bandit Director Jesse Moss

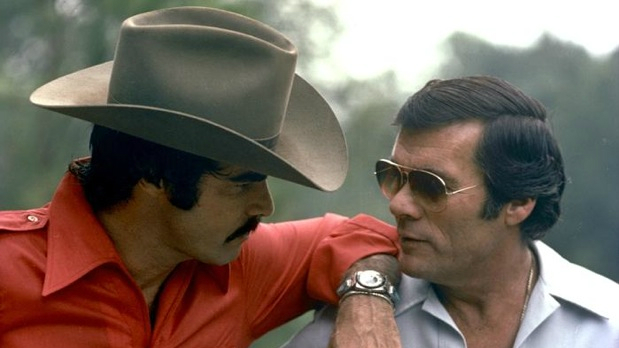

Burt Reynolds and Hal Needham

Burt Reynolds and Hal Needham Jesse Moss’ documentaries often take on heavy material, and his last film — 2014’s The Overnighters — was no exception. The experience of profiling pastor Jay Reinke — a North Dakota minister whose decision to open up his congregation to homeless laborers seeking oil field work placed him at odds with his flock — took a heavy toll on Moss. His new documentary The Bandit is a completely different kind of movie, an archival-based profile of Burt Reynolds and his good friend Hal Needham. Moss examines their complicated relationship through the making of 1977’s Needham-directed Smokey and the Bandit, a film still in regular circulation on TV. Fittingly, Country Music Television (CMT) financed the documentary. Prior to his SXSW premiere, Moss hopped on the phone to discuss the enigmas of Burt Reynolds, the learning curve required in working with a great deal of archival material, and how his films repeatedly return to the theme of dual identities.

Filmmaker: This documentary is coming out at a time when Burt Reynolds is making another comeback push, including a series of magazine profiles tied to his new memoir. Did you start this project as part of that publicity push, or did you have the idea independently?

Moss: We knew from the beginning that he had been working on a new memoir, but this was not related. It came about because I was talking to someone who works at CMT, the network that financed the film. To be honest, Smokey and the Bandit was not a film I was initimately familiar with, but I knew it. We were talking about that film, and whether there was a documentary to be made about it. The original conception was a film that would explore its legacy and impact, why it’s such a popular film for some people. That wasn’t a documentary that I was particularly interested in, and not knowing a lot about the making of the film, went away and thought about it. I realized there was a great opportunity to make a film about Burt Reynaolds and Hal Needham, who was Burt’s best friend, stunt double and roommate for much of the ’70s. Smokey was a prism to look at Burt’s life and relationship with Hal, their journey and how they intersected and came to make that film. We came up with that idea without knowing whether Burt would participate. CMT liked that idea and we approached Burt about the project. He was receptive.

One of the first things we shot for the film was, we visited his house in Florida and spent two days interviewing him, filming his acting class — he still teaches acting in Florida — and spent some time with him and his friends. It was clear when we sat down with Burt and started asking him about his career and some of those films in the ’70s that it was really exciting to him. He gave us access to his personal archives, which were really incredible. They were not particularly well organized, but he kept everything from his life in scrapbooks. I think he was excited that there would be a serious film about his career and relationship with Hal Needham. Once we realized we had his full support and cooperation, we realized we could make the film we set out to make. I haven’t read the book. One of the important choices we had to make was, what was the time period we were going to focus on? Burt and Hal both had very long, productive, complicated lives, and one documentary couldn’t do it all. We

were really interested in that period of Burt’s film roles from Deliverance and those early good ol’ boy roles to Smokey and the Bandit. The film does back up and look at how they met each other on television Westerns in the ’50s, but we kept our focus pretty specific, and the film doesn’t go beyond 1977. There’s a post-script that’s present-day, but it effectively ends at that point. The current memoir that he’s written is a lot of later life material, which is something we were not going to focus on.

Filmmaker: I know about the cultural impact of Smokey and the Bandit, but only abstractly. I know it’s been aired repeatedly on television forever, and seen by a lot of people, but I’ve never actually seen it. What’s your relationship with the film?

Moss: I was seven when Smokey came out. That was when that I just started going to movies, but that wasn’t the film that imprinted as deeply on me as Star Wars. I knew of the film; I knew it laid down a kind of template for the action-comedy that came in many forms on television and film after that, that you could point to the film as one formative influence on that genre, which is a huge genre. But I wasn’t somebody who had seen the film 200 times and memorized every line of dialogue, which some people have. So, I kind of went in cold, not knowing much about it or Burt Reynolds, other than this impression many of us have from Deliverance, Boogie Nights, fragments of Smokey, and his personal life. A loose collection of ideas and images associated with Burt: knowing he had been a sensation for his film roles, for his television appearances, for his willingness to take his clothes off, for his appearances in Cosmopolitan. I was pretty young, so I didn’t have much of a relationship with that Burt Reynolds, but I was interested in who he was, both as a human being and as a phenomenon.

Hal was his alter-ego in many ways. The Burt Reynolds we know from some of his film roles, this southern superhero — the stunts, the car movies — owe a good deal to the work Hal Needham did as a stunt double. Up to the point he directed Smokey and the Bandit, he was the most famous, most highly paid stunt double in the industry, but not very well known beyond. To me, I immediately saw the documentary as a buddy movie, much like a Burt Reynolds movie from that period. It was a buddy movie about a buddy movie.

Filmmaker: What was it like working with a broadcaster from the get-go rather than working independently?

Moss: The very first film I ever made was financed by HBO. They came in early in development and production but ended up financing the film fully. It wasn’t a feature, it was an hour, and that was a film that was only semi-successful and kind of a cautionary tale for me. I’ve had great success working on my own. What’s unusual is that there are not too many television networks that support feature-length documentaries. I thought this was an exceptional opportunity. In a new commissioning strand, CMT has been commissioning filmmakers to make one-off docs. They gave me great freedom and space, and willingness to support the film as a festival film, potentially as a limited theatrical

release, which all parties want to happen. It’s been kind of great, and by the very nature of this film — the amount of archival material, the licensing of that material — it would have been very, very difficult to make it in the more independent ways I’ve made docs. Just to ingest the thousands of hours of archival footage and images, setting up a process to deal with that would be hard. Perhaps with Burt’s name you could go raise money privately, but CMT was a partner that was really willing to support my vision of the film.

Filmmaker: How did you approach the archival aspects of the film? That’s a new challenge for you.

Moss: I’ve never worked on a project with this kind of scale and complexity of archiving. It’s a steep learning curve. I think we were not fully prepared for the complexity of licensing and the cost, and also the complexity of some of the fair use arguments that are made with some footage that falls under those parameters. The upside is, much of the footage had not been seen since the early ’70s. There was a period where Burt Reynolds hosted his own talk show, and we were able to get copies of the show from Burt himself. Together, Burt and Hal are really extraordinarily compelling and charismatic, and we let them tell the story in their own words. We did interviews with friends and colleagues from that period, but really it was just letting the footage speak. That’s always the opportunity for a film like this, to allow the arhicval footage to speak for itself and create the motion and psychological complexity of the story. It was a good, fun challenge.

Filmmaker: In an interview we ran with you when The Overnighters came out, you talked about how difficult the film was to make and needing a break. Was this film your chance to take a break from heavier material?

Moss: My friend Esther Robinson described this film to me as my rebound film. As you know, making The Overnighters was a really, really heavy psychological and financial experience, and I couldn’t make another film like that. This was a great opportunity to step into another filmmaking process. All filmmaking comes with its own burdens, but it gave me some time, and the working method was less impactful on my family life, so that was important. This was also a way to take on an archival film. We’ve seen some really inspiring examples in the last few years, and the mold has been broken. So I was inspired by that challenge and working in a new grammar, and taking on this titanic and yet complicated, mysterious character — understanding who he was, and excavating Hal Needham from history, and putting them together and understanding the complexity of their relationship.

There’s thematic overlap between this and The Overnighters on two levels. One, it’s about working class masculine ideneity in some form, but it’s also about the layers of Burt’s identities. I won’t say that Hal was his secret, but stuntmen are not supposed to step out of the shadows. And Hal, who lived in Burt’s shadow and helped to make that character, did step out of the shadows. That was interesting to me, that kind of split identity. That’s a theme that from my very first film, about an imposter with a double identity. I’m interested in that theme of doubling, so it was an opportunity to continue that investigation but in a very different way. Also, The Overnighters was a tragedy, and this was a film I saw as a buddy movie, and also as an action comedy. There were a few ocacasions on The Overnighters when we laughed , but mostly we cried. For this, the footage is funny, Burt Reynolds was funny, there was a lot of velocity to the story. I don’t know if you ever saw Speedo, but this film has the spirit of that film and moves fast.

One of the things that Hal Needham’s widow Ellen said to me is that Hal hated documentaries. I asked, “Why did he hate them?” “Because they’re boring!” So the goal I set for myself was to make a documentary that Needham wouldn’t have hated.