Back to selection

Back to selection

The Adventures of a Furie-ous Evangelist: Looking Back After a Toronto International Film Festival Premiere

My book editor on Sidney J. Furie: Life and Films — the venerable, celebrated Patrick McGilligan — once told me in an e-mail, “There is nothing like one’s first book. You forever feel a special connection to that first subject matter. I feel the same fondness about James Cagney, my first book’s subject, as you probably do for Sidney J. Furie, your first.” For certain, I find that to be true. But I feel an even stronger bond to Furie, by sheer virtue of the fact that I was the very first to write a book — or, for that matter, any kind of serious study — on him. Because of this, I was forced to beat a loud drum incessantly. Even after having moved on to my second and third book projects, I still cannot shake my admittedly zealous crusade to score the underappreciated Sidney and his films more playtime and recognition. The fight to be heard and acknowledged continues, onward, onward, onward.

The long-time-coming North American premiere of Sidney’s history-making sophomore feature, A Cool Sound from Hell(1959) at the Toronto International Film Festival on September 16 was a momentous occasion considering that the film never once played on the continent after its completion. My efforts to locate and resurrect the film are detailed in the Filmmaker Magazine article I penned in June 2014. The film stars Tony Ray, son of director Nicholas, who was, at the same time, shuttling between shooting Cassavetes’ Shadows (1959) in New York and A Cool Sound from Hell in Toronto.

Here, I look back on many unexpected incidents and developments that followed my book’s November 2015 publication, and the aftermath of A Cool Sound from Hell‘s long awaited restoration.

In December of last year, I attended a public San Francisco screening of Kent Jones’s documentary Hitchcock/Truffaut with my best friend Aaron. At that point, my book had been on the stands for almost two months and seemed to be selling quite well for a “specialty item” covering the life and career of my biggest “pet cause” filmmaker, whose name, at a mention, often ignited uncertainty and skepticism rather than instant recognition and/or holy-holy-holies.

While my buddy and I waited for the scheduled screening to draw near, we killed time at a nearby bookstore that stocked my labor of love. The Furie Gospel was available to those whose cinematic “souls” were open, har-har. ‘Tis a grandiose analogy, granted, and slightly cheeky at that, but I took heart knowing that Sidney now shared literary shelf-space with other directors of note and prominence. As an “F,” he sat beside another favorite filmmaker of mine: Rainer Werner Fassbinder.

Inside the theater, Aaron and I sat eavesdropping on the erudite, clearly fun-loving quartet seated directly behind us. After a period of discussing the re-release of Satyajit Ray’s Apu trilogy and the Castro Theater’s then-recent screening ofThe Reckless Moment (1949), one of them mentioned having caught an unexpected gem on television: Furie’s Sheila Levine is Dead and Living in New York (1975), which had aired on Turner Classic Movies just two nights prior. Our ears were pricked, because this was one of the unjustly maligned films that I vigorously championed in my book. In rather dramatic fashion, the four of them sang its praises with unqualified enthusiasm, and wondered how they had been ignorant of its existence until the TCM showing, which was the first proper 2.35:1 widescreen presentation of the film on American television. They applauded Jeannie Berlin’s and Roy Scheider’s performances, and (most astonishingly) marveled at the film’s sensitive direction, ‘Scope camerawork, moody, dark lighting style and careful, burnished color palette.

I turned to Aaron and exclaimed, “Can you frigging believe this?!” The evening quickly entered into some outright surreal territory. I listened for a bit more before I could no longer resist, turning to inform them that I had written a brand new book about the director of their favorite new discovery. To be sure, they were as tickled and flabbergasted as I was. One of them knew that Sidney had also directed The Ipcress File and Lady Sings the Blues. When the flickering light of Hitchcock/Truffaut came to life, our attentions were diverted.

As we exited the theater, my excitement about the earlier incident was such that I simply had to call Sidney to tell him what had happened. Sheila Levine is Dead and Living in New York was, after all, the film whose failure hurt him the most. He once explained to me, “It was a film I really thought worked, more than other films of mine that flopped. When the critics tear a film apart, what can you do? I’ve always just moved on. But that one hurt.” I then put my witness, Aaron, on the phone, to verify that this was not a fabricated incident, manufactured for consolation or ego-mending. Yes, twists of fate among the worldwide cabal of filmmakers and cinephiles are often some of the most mystifying.

Shortly after this encounter, Paramount Pictures made the film available on YouTube for free as part of their Vault series. The YouTube user reviews, in conjunction with ones on other sites ranging from the TCM website to IMDb, suggest a growing respect and slowly shifting reputation for that particular film and many of Sidney’s other forgotten or besmirched pictures, including The Appaloosa (1966), The Naked Runner (1967), Little Fauss and Big Halsy (1970), and Hit! (1973). Films maudit by the vault-ful! I also find that cineastes have become more attentive to The Ipcress File (1965), The Boys in Company C (1978) and The Entity (1982) explicitly as the films of a director with a refined, definable sensibility. As I reminded Sidney on the phone that night, “Films live! They just don’t exist for one day and get killed off by critics at the moment of birth. Like those who create them, they live their own lives, and the right people will find them, more often than not.”

After a forty-years absence on the home-video market, another of Sidney’s great forgotten films, Little Fauss and Big Halsy (1970), starring Robert Redford, Michael J. Pollard, and Lauren Hutton, finally makes its debut on DVD and Blu-Ray this October, courtesy of Olive Films. The longstanding rights issues revolving around the Johnny Cash soundtrack have finally been resolved. I am here tempted to ask, “Why now, after all this time?” The film had long only been available via VHS-sourced, recorded-from-TV, badly panned-and-scanned copies that compromised Furie’s compositional mastery.

I might very well be reading into all this, with that old wishful glint in the eye, but could this be the beginning of some kind of renaissance for Sidney J. Furie?

I’ve met many Sidney J. Furie fans who did not know that they are fans of his. For example, I’ve had this exchange any number of times:

“Never heard of him…what did he direct?”

“The Leather Boys, The Ipcress File, Lady Sings the Blues, The Boys in Company C, The Entity.”

“Wow, I love those films! One guy did all those?”

“And many other great films too!”

I would transform into a missionary before their very eyes. There were also a number of “conscious” Furie fans who contacted me after the publication of the book. All this solidified my confidence that the man and his work do have a quiet but hearty following further awakened by the emergence of a book to both tell his story and re-classify the films as the clear work of an auteur.

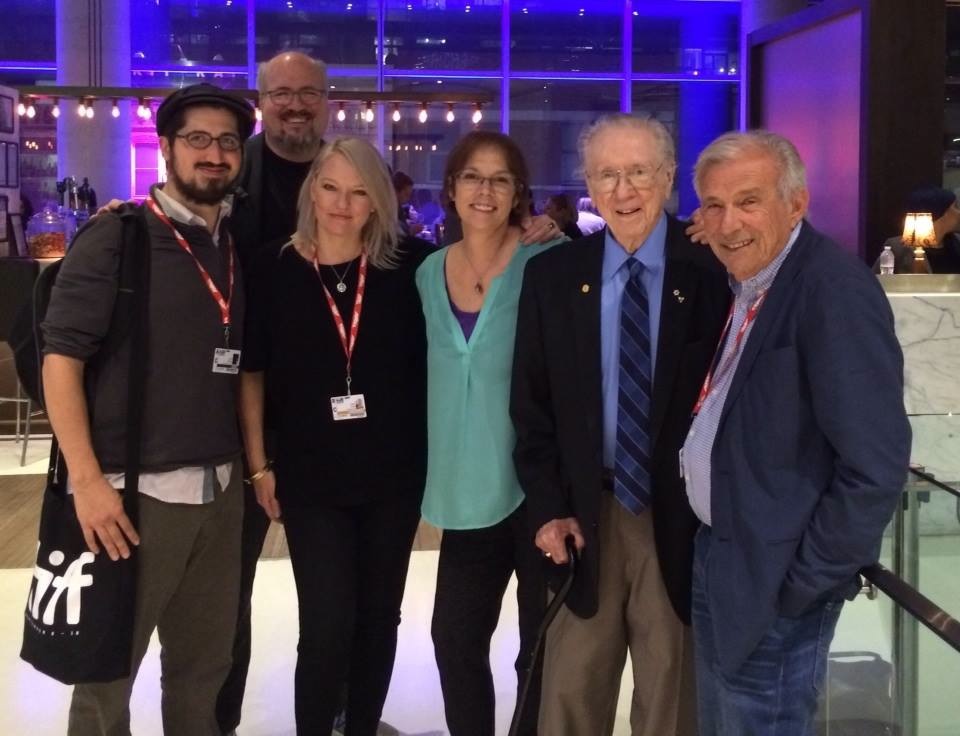

The crowning achievement of my evangelical efforts is undoubtedly my excavation of Sidney’s second feature, A Cool Sound from Hell (1959), and the success in getting it shown as part of Toronto International Film Festival’s Cinematheque program. I was present with Sidney in Toronto; between walks around town (during which Sidney took me on a tour of some of Cool Sound‘s shooting locations), we did radio interviews, answered Q&A questions, and signed some of our books. Reaction to the film was extremely warm, and a wider re-release looks like it will be coming down the pike (can’t speak specifically to this until it is officially announced, but a deal is in the works with a first-rate label known for restorations and giving new life to forgotten films). What a road this has been!

Sidney, who was not the keenest on showing such an ancient, “immature” work after all these years, was immediately consoled by the fact that it appeared in the Cinematheque program next to films like The Battle of Algiers, One-Eyed Jacks and Jonathan Demme’s Something Wild. Sidney’s appraisal of A Cool Sound from Hell is, to me, belied by the film’s ingenuity and sophisticated visual design, exemplified in two set pieces in the sample videos featured above and below.

A Cool Sound from Hell is a work that was important to the development of a Canadian film industry at a time when none existed. Writes TIFF director Piers Handling in the foreword of my book, “It remains a wonder to behold that [Furie] started making striking, bold, and of-the-moment feature films in Canada when the only game in town was the short films being made by the NFB. Furie and his films captured a country struggling to establish its identity.” On the festival website, senior TIFF programmer Steve Gravestock declares, “The wait has been worth it. [It is] simultaneously an early work in a memorable career, a milestone of anglophone Canadian cinema, and a vital record of a Toronto that was.”

I am still laboring intensively to score Sidney and his films their first retrospective. It is easy to grow impatient, because many venues count on tried-and-true programming for their revenue stream. Hinging any prominent series on a director that seems to lack such cachet is a risk. In Sidney’s case, I think: high risk, high reward. We should never be bashful about artistic discovery, or rediscovery. The Leather Boys, The Ipcress File, The Lawyer, Lady Sings the Blues, The Boys in Company C, The Entity, the first two independent films made in English Canada, and much more: all critically lauded films in what is, indeed, a striking resume. Part of the problem is that the cognoscenti blanch at seeing Superman IV and the late-career direct-to-video action-fare on his resume, and then quickly flee for the hills. That trigger-happy reaction among this intelligentsia gets me quite wearisome in the extreme.Obviously, my advice is to look closer. Maybe you’ll find one of our greatest living directors, and that is a statement made in earnest. I say that as someone whose favorite filmmakers are Jacques Rivette, Peter Watkins, Joseph Losey, Max Ophuls, Powell & Pressburger, Nic Roeg, Jean Vigo, Luchino Visconti, John Huston, Ritwik Ghatak, and Robert Altman, among others. But isn’t it that bold, impassioned pronouncements concerning lesser-known or esoteric artists are met with automatic skepticism, or accused outright of hyperbole? As Oscar-winning screenwriter and one-time British film critic Paul Dehn once jested, “I pick my words as cautiously as I sink my boats.” As I titled my original 2012 pre-book blog article about the man and his career, Sidney J. Furie is alive and well and living in films.