Back to selection

Back to selection

Robert Bresson x 2 via NYRB Classics

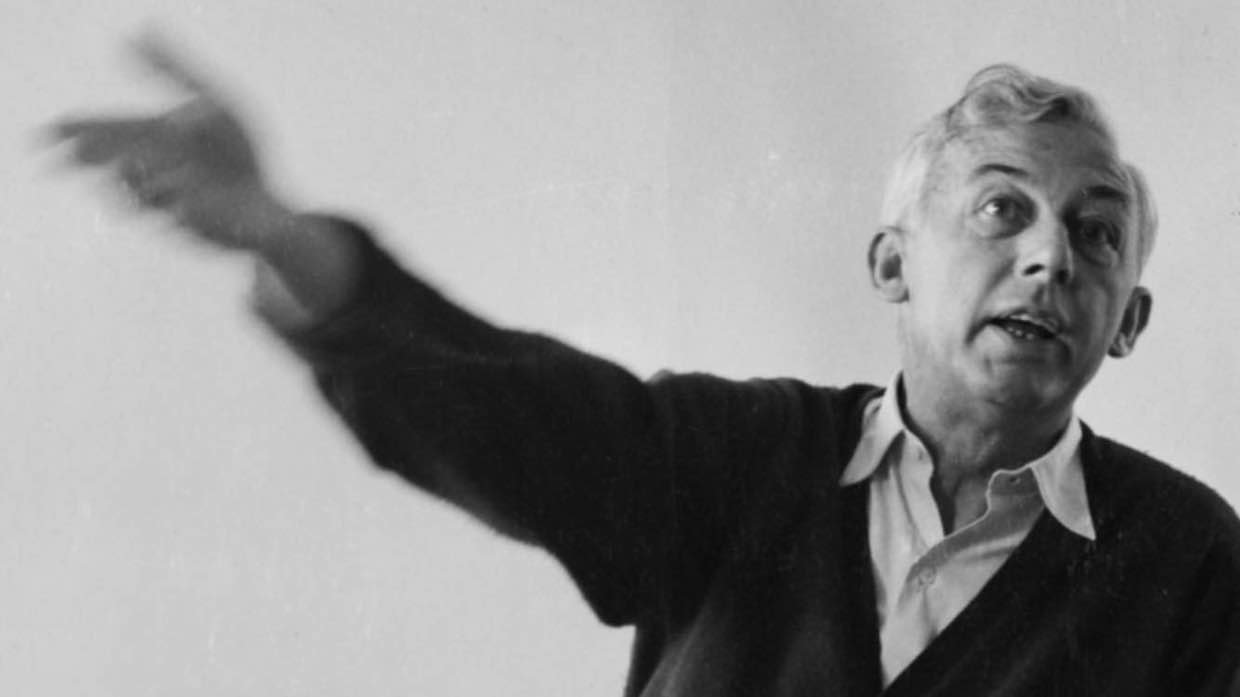

Robert Bresson at Cannes, 1962 (Photo by Jaakko Tervasmäki/Courtesy of NYRB Classics)

Robert Bresson at Cannes, 1962 (Photo by Jaakko Tervasmäki/Courtesy of NYRB Classics) NYRB Classics is not only reissuing Robert Bresson’s Notes on the Cinematograph but publishing Bresson on Bresson, a freshly translated interview collection. While the imprint’s never published a straight-up film book before, the former isn’t that eyebrow-raising: Bresson’s slender volume of koan-like declarations has been a fetish object outside of Film World since initial publication. Bresson on Bresson, though, is a different proposition. Interview collections (like the Conversations with Filmmakers series published by the University of Mississippi) are both valuable and inherently redundant, as subjects inevitably are forced to give the same answers over and over through the years. The interviews aren’t trimmed down to their non-overlapping essence, so a little impatience inevitably sets in: you need to be really interested to commit.

Bresson described Notes as a “short technical book about the cinema,” which is an interesting way to define “technical.” Alongside a little discreet bitching about producers, there are indeed some sturdy, applicable and concrete directives within: “Reorganize the unorganized noises (what you think you hear is not what you hear) of a street, a railroad station, an airport…Play them back one by one in silence and adjust the blend.” Much of this, however, is in the realm of aphorism: re-opening the volume at random, my eye lights upon “Nothing too much, nothing deficient.” Will do! What emerges more broadly is a sense of Bresson’s determination to think through a total system of filmmaking that would be his alone, starting with the construction of a specialized vocabulary: his repeated insistence that his work was “cinematography,” compared with the “filmed theater” of the “cinema,” is probably the most-repeated sentiment of his career.

I hadn’t given any serious thought to Bresson’s films (all of which, minus his rare first one, I’ve seen) in a few years, and it’s fortuitous the NYRB Classics initiative comes shortly after seeing Angela Schanelec’s The Dreamed Path (which I wrote about here). It’s a film I admire and also the closest thing I’ve seen to Bresson cosplay, with a liberal number of Close-Ups Of Hands. Isolated body parts don’t seem to mean the same thing to Schanelec that they did to Bresson, who insisted a) on the general principle of synecdoche as a way of sharpening the senses b) that the unconscious self-expression of appendages is probably more revealing than dialogue. Schanelec’s close-ups don’t seem to perform any such work: they’re nods towards a stylistic lineage that she then fragments in a narrative whose increasing elisions leave us pleasurably lost rather than rigorously locked-in. Ricky D’Ambrose, a director I’ve known since college whose recent short films have also been working through some obvious Bressonian homages, was appalled when he saw it: “I don’t ever want to make films like that,” he wrote me in an email.

The question of direct shot imitation, then, seems not so important and I don’t see it coming up a whole lot — Bresson’s visual sense was too particular to be terribly useful as a starting template in pretty much any other context. In more indirect ways, Bresson’s influence is more obvious: the emphasis on flattened performances from non-professionals and challenging viewer attention through severity, durational and otherwise, is pretty groundbreaking. His private conceptual vocabulary is Bresson’s alone, but the broader idea of a cryptic, self-created lexicon is familiar to any cinephile who’s gone so deep down their viewing trail that ideas and evaluative scales that make intuitive sense to them can seem impenetrable to anyone who hasn’t been a fellow traveler for sometime.

There’s something deeply pleasurable in this refusal to serve, to work only on one’s self-coined terms and to reserve the right to either elucidate or obscure those terms. It’s a fun coincidence that Bresson speaks of his total admiration for Cézanne — Straub-Huillet, who adored Bresson and took the idea of total artistic integrity regardless of any hypothetical viewer far further, similarly admired the painter. How to explain this shared affinity? For these filmmakers, it’s a fondness so obvious as to barely require further explanation. The fun when approaching such intractable filmmakers, with their penchant for stating obscure predilections as the most obvious thing in the world, is in learning to feel what they want you to feel or not feel — to dive into an open challenge, seek annotative help, and emerge with a richer sense of what film can be. These volumes shed some light on Bresson’s intentions and (slightly) changing feelings about his process over the years, but they’re stimulating as one kind of model for filmmaking: to try to conceptualize yourself into originality before the writing even starts.

NYRB’s volumes go on sale November 15. The retrospective “Bresson on Cinema” starts at BAM today. Another Bresson series starts at Metrograph on November 23.