Back to selection

Back to selection

The Art of the Possible: Charles B. Pierce’s Arkansas Cinema

The Town That Dreaded Sundown

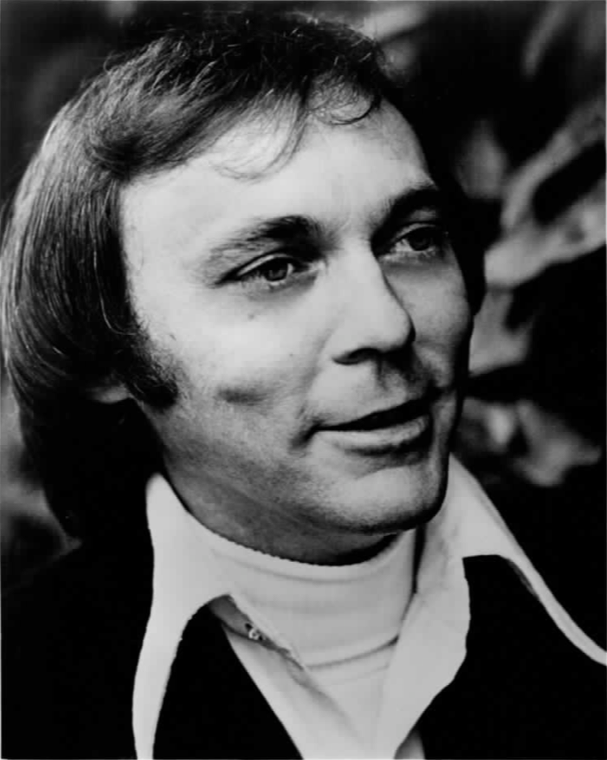

The Town That Dreaded Sundown Remembering her filmmaker father Charles B. Pierce, Dallas designer Amanda Squitiero first mentions the place he called home. “Arkansas claims him and he claimed Arkansas,” she says, having recently marked the seventh anniversary of his passing.

Emerging regional filmmakers now see more opportunity than ever to achieve the most ambitious of visions on skid-row budgets. Before the digital revolution, one might strain to remember a time when independent cinema could exist outside of the New York and Hollywood ecosystems. In this regard, Pierce realized cinema as the art of the possible, which could exist and even thrive in a place like Arkansas. In that routinely undervalued zone between New York and L.A. – that vast expanse often pejoratively referred to as “flyover America” – Pierce directed thirteen feature films, the majority independently financed.

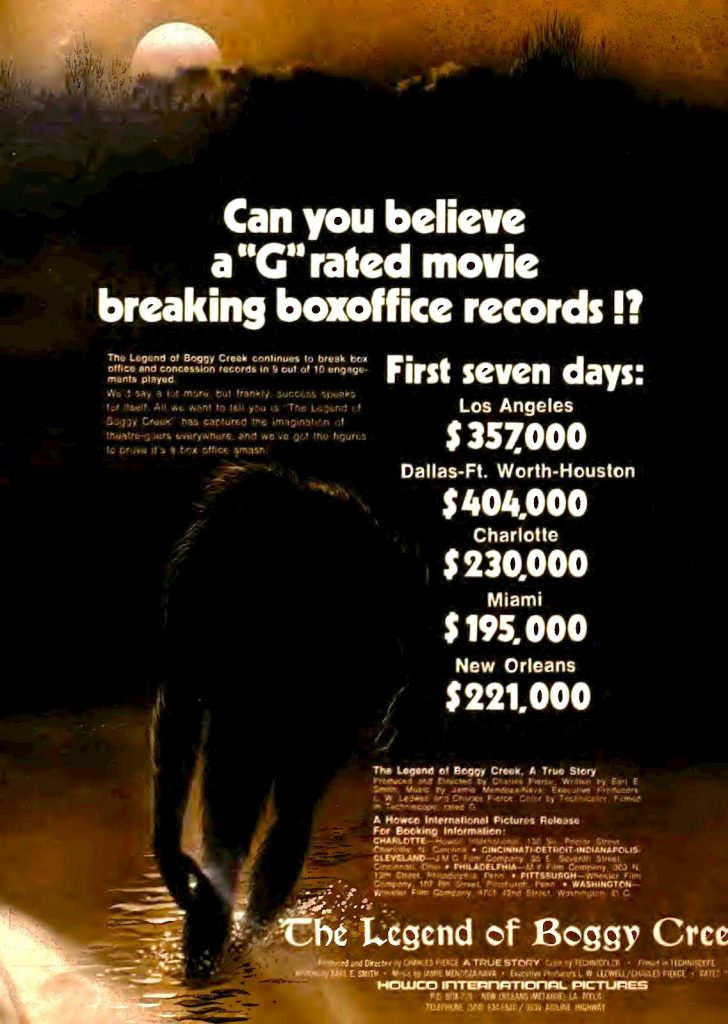

Today, Pierce is perhaps best known for writing the famous Dirty Harry line, “Go ahead, make my day” (based on his own father’s catchphrase) for Sudden Impact (1983). As a writer-director, he is regarded by some as an anonymous purveyor of schlock and innocuous family Westerns. It is oh-so-easy, however, to argue otherwise. His output gains respect and admiration with each passing year as more of his titles hit the video market. But cinephiles and film scholars are tragically quick to forget or write off Pierce as a trailblazer or icon of any stripe, despite his making independent film history with The Legend of Boggy Creek (1972), a $25 million golden goose produced on a $160,000 budget. Adjusted for 2017 inflation, that’s a $145 million gross.

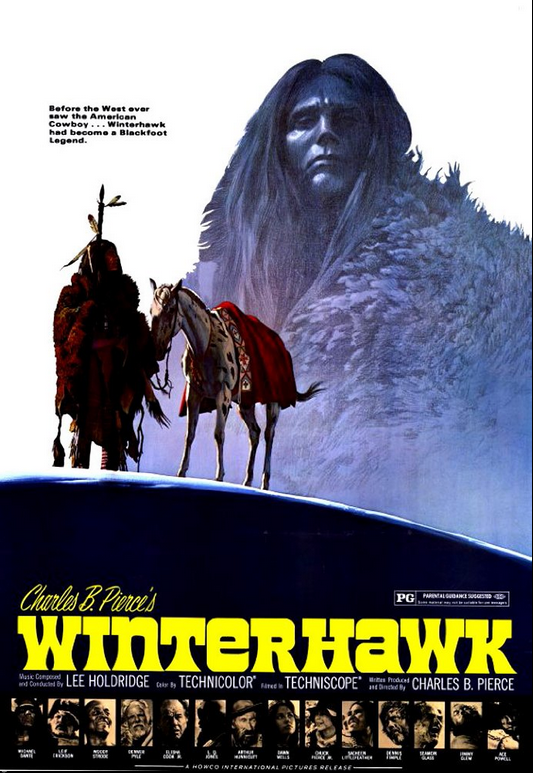

Educated cultists of the era branded him the George Romero of the South, but that’s disingenuous in many ways. Pierce’s most personal films reference canonical American motion picture classics with a surprising and unusual level of reverence and visual sophistication (evidenced especially in his early Westerns). Winterhawk (1975) and Grayeagle (1977), his two meditations on The Searchers (1956), both fit within the contours of the panoramic John Ford Westerns that open the American frontier epic to themes of tradition, family, chivalry, spirituality and rugged individualism.

Pierce’s flair for CinemaScope landscapes recalls both Ford’s and Anthony Mann’s in terms of sheer scale and depth. Background history is often literally framed through a foregrounded intimacy. While Ford’s sensibility is informed by his Irish-Catholic upbringing, Pierce’s equally humane sensibility flows mightily from his Arkansas Baptist heritage. “Amazing Grace” appears in many of Pierce’s pictures as a key directorial trademark.

In the prime of his career, Pierce directed many alumni of the classic Ford pictures he cherished, including Slim Pickens, Jack Elam, Ben Johnson, Paul Fix, Jeanette Nolan, Woody Strode, Denver Pyle, “Iron Eyes” Cody, Leif Erickson, and Elisha Cook Jr. In The Searchers, Lana Wood played the ten-year-old incarnation of Natalie Wood’s character; in Grayeagle, she essentially plays the Natalie Wood surrogate. Beyond these casting coups, there was a pertinent souvenir that Pierce most prized: a personal letter from John Wayne, applauding him for his efforts in keeping the Western genre alive. Pierce also prized the grandeur of the big screen; as Squitiero recalls, “You couldn’t have given him a big enough canvas, or a wide enough one.” Indeed, this is a rare proclivity for an independent of his era, and perhaps any era.

Early regional cinema is exemplified by pictures like Joseph L. Anderson’s Spring Night, Summer Night (1967, southeast Ohio), Tobe Hooper’s Eggshells (1969, Austin, Texas), Wendell Franklin’s The Bus is Coming (1971, Cleveland, Ohio), Eagle Pennell’s The Whole Shootin’ Match (1978, Austin, Texas), Rob Nilsson and John Hanson’s Northern Lights (1978, North Dakota), Victor Nuñez’s Gal Young ‘Un (1979, Central Florida), Penny Allen’s Paydirt (1981, southern Oregon), and Horace B. Jenkins’s Cane River (1982, Natchitoches Parish, Louisiana). In the able hands of these makers, some of whom were neophtyes, it’s easy to deem regional filmmaking a heroic act without fear of hyperbole.

Today, regional cinema at its boldest is exemplified by directors like Mark Thimijan (Lincoln, Nebraska) and Paul Harrill (Knoxville, Tennessee). Harrill won the 2001 Sundance Film Festival Short Filmmaking Award for Gina, An Actress, Age 29. He recently directed his first feature-length drama, Something Anything, also shot in and around Tennessee. Says Harrill, “For me, the fundamental premise of regional filmmaking is this: Where a story happens matters. There is an integrity to shooting a film regionally, and it goes beyond landscape.” He nevertheless concedes, “It can be challenging making regional films, even today. I’m in awe of filmmakers like Eagle Pennell, Penny Allen, Charles B. Pierce, and Jon Jost, who managed to produce important regional films well before the digital age.”

Mark Thimijan accounts his tenure as Lincoln, Nebraska’s filmmaker-in-residence: “I started out there in the nineties around the time Alexander Payne shot Citizen Ruth (1996) in Lincoln and Omaha. I ventured to L.A., lived there for a couple years, came back to Lincoln, and found that I was this island. In my time, I was probably the only person in Lincoln with an itch to make films. There was just no one else doing what I wanted to do.”

Thimijan then set about shooting his first short film on 35mm film. Where was the closest place to rent a 35mm motion picture camera? Minneapolis, Minnesota…over 400 miles away Thimijan arranged to meet the rental house representative halfway, in Des Moines, Iowa. “It was kind of like an illicit drug deal, except that it was this beautiful machine, but I have to say that laying my hands on it still got me high. Locals thought I was crazy wanting to shoot 35mm on a such a project, but I was determined. Part of it was that I was still skeptical about digital technology at the time.”

Thimijan sought the help of able hands (some of whom previously crewed on Alexander Payne’s About Schmidt), cobbled together all the local talent he could find, and then delivered the exposed stock to Los Angeles for processing. The Girl Who Could Run 600 Miles Per Hour toured festivals in 2006 and 2007. Since then, Thimijan has shot two feature-length films digitally: Barstool Cowboy (2008) and She Lives Her Life (2016). The latter is a loose, Cornhusker State remake of the Godard classic Vivre sa vie (1962).

Many of the stories behind Charles B. Pierce’s debut picture are not so dissimilar. It is here important to dispel the myth that Pierce enjoyed a tenure as a Hollywood set dresser. Many bios, remembrances, and obituaries erroneously attest to this credential. “That was another Charles Pierce entirely,” Squitiero clarifies.

After a stint as a TV weatherman in Shreveport, Louisiana, Pierce gained notoriety as Mayor Chuckles, the star of the popular local children’s television show The Laffalot Club. With his knack for fine art, Pierce enhanced the Mayor Chuckles schtick by sprucing up and completing the drawings and paintings that the show’s young guests would scribble on the air. (When Pierce became a film director, the handsome posters he commissioned from illustrator Ralph McQuarrie were central to his films’ identity on the marketplace.)

1971 saw his return to Arkansas, inspired by a wave of chilling stories he heard firsthand about a sasquatch-like monster haunting the swamps and forests near the town of Fouke. In collecting eyewitness testimonies, he set out to craft a faux-documentary portrait of the fear and trembling that enveloped parts of that community.

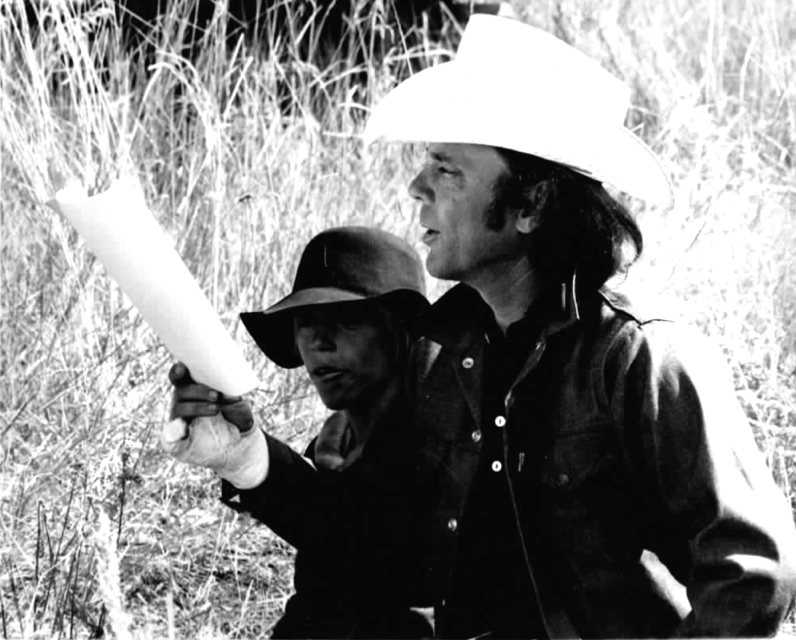

Pierce secured $160,000 in financing from Arkansas trucking company magnate L.W. “Buddy” Ledwell, for whom Pierce had done a visually striking, hit commercial that played throughout the Southwest. Between October 1971 and April 1972, with nine Texarkana high school kids moonlighting as his crew, Pierce shot his opus on a borrowed Techniscope-capable camera, functioning as his own cinematographer.

Upon picture wrap, he drove the exposed film cans to a lab in Burbank, California, for processing. In editing, interviews were paced with staged dramatic sequences, and underscored by a number of original, homestyle folk tunes provided by composer Jaime Mendoza Nava, who would become one of Pierce’s key collaborators.

The film made $55,000 in its first three weeks of playing the Perot Theatre in Texarkana. When The Legend of Boggy Creek expanded to other parts of the country, it eventually raked in its then-whopping $25 million in receipts, becoming the tenth highest grossing film of 1972. Its surprise success spawned a copycat cycle of “creature features” which dominated grindhouses and drive-ins throughout the seventies. Its “mockumentary” style later influenced Daniel Myrick and Eduardo Sanchez in the creation of their indie blockbuster The Blair Witch Project (1999). Says Myrick, “We wanted to tap into the primal fear generated by the fact-or-fiction format like The Legend of Boggy Creek. It’s certainly the one film that most inspired me.”

Concerning Boggy Creek’s then-innovative approach to subverting the documentary form, Squitiero remembers, “He really did believe that the Fouke Monster existed, so he thought that the documentary form best suited it. I think he also knew it would be scarier if people had to consider the possible truth of everything.”

To elaborate on the motives behind Pierce’s structural design, the on-camera interviews unfold much like folk stories, giving the film the rich, resonating impact of oral history. Boggy Creek is a cross-genre essay on collective memory and shared experience, and specifically how memory and common experience can unite and forever bind communities. This gives the interspersed horror sequences an unexpected weight that Mendoza-Nava’s suitably quaint folk tunes help to accent. The notion of oral history and heritage would furnish Pierce with a sense of thematics that pervade all his work.

Newly flush from the lucrative yield of his debut triumph, Pierce embarked on a much more personal, non-genre film with Bootleggers (1974), the story of two feuding families living in the Ozarks of the 1920’s. Shot by then fledgling cinematographer Tak Fujimoto (The Silence of the Lambs, Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, The Sixth Sense) in 2.35:1 widescreen, Bootleggers proved a disappointment to the ever hopeful, lovably quixotic Pierce, who, according to Squitiero, considered it one of the best pictures of his career. (Indeed, in this author’s opinion, Bootleggers is a worthy and even passionate work that still awaits rediscovery.)

“It’s amazing to me that he just always made things happen,” says Squitiero. “He was so skilled at scraping together a way to do things. He had a way to do anything. But he would laugh at himself because he couldn’t go out and do a gangster film or a standard love story. He always felt he would fall on his face, because he would only deal with subjects that touched him – specifically, films where he felt he had something to say. He loved Westerns and he loved horror films, and everything he did was personal. He still wanted to make films that he felt people would pay to see.”

As to his process, she recounts, “If the budget required, he’d be the sound recordist, the gaffer, the grip, and an actor. He wanted as much artistic control as he could have, which is why he needed to be an independent. He also loved giving new people chances. Some of those same folks who are still in the industry got their start under my dad.”

Pierce lit some fires under others, stirring them into action. His close childhood friend Harry Thomason and Boggy Creek co-screenwriter Earl E. Smith would go into Arkansas-based motion picture production for themselves. Smith directed the horror-Western hybrid Wishbone Cutter (1976, a.k.a. The Shadow of Chikara), starring Joe Don Baker and Sondra Locke. Thomason helmed five Arkansas films, including Encounter With the Unknown (1973), The Great Lester Boggs (1974), and So Sad About Gloria (1975), before taking up a career directing television (Designing Woman, Evening Shade). (Thomason also shot a short behind-the-scenes documentary on the set of Winterhawk.)

The first in Pierce’s series of Westerns, Winterhawk (1975), had its roots in a vision conjured by magic hour light as it hit a distant figure in a lonely landscape. “He had a very strong feeling about Winterhawk,” says Squitiero. “He used to drive a lot from Texarkana to L.A. and would race across the desert. One time, he stopped and saw an Indian standing beside a jeep looking off into the sunset. The way he described it, a hundred years disappeared, and the image became an Indian standing beside his horse. On the rest of the drive, he dreamed up a story of a proud, forgotten American Indian.”

He followed Winterhawk with a cycle of Native American-themed Westerns, including Grayeagle (1977), Sacred Ground (1983), and Hawken’s Breed (1987). Another frontier epic, The Winds of Autumn (1976), follows a 12-year-old Quaker boy’s lone search for vengeance and features Native Americans only peripherally. The Winds of Autumn, a picture to which he felt close, features more than a few passing nods to Pierce’s favorite film, Shane (1953).

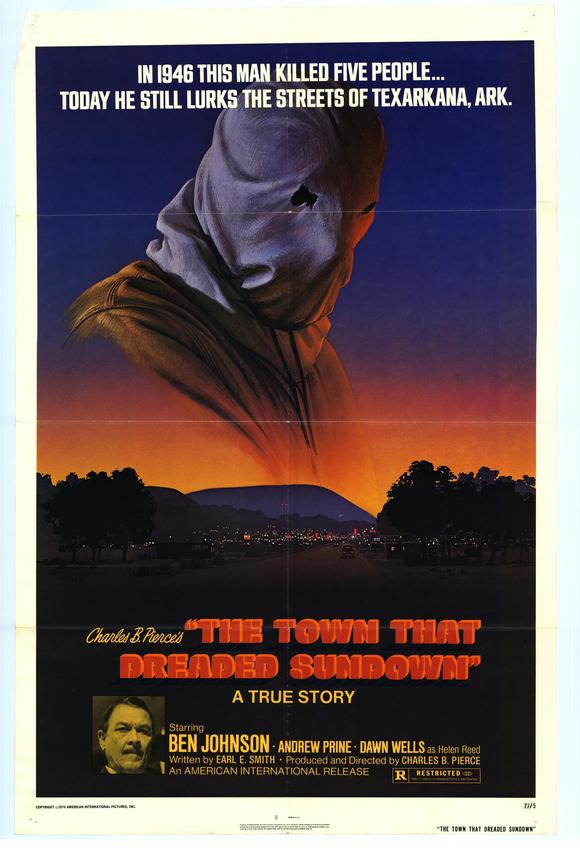

In 1976, Pierce rose to prominence again when he delivered another based-on-fact drive-in horror hit. The Town That Dreaded Sundown recounted Texarkana’s most infamous cold-case, that of the Phantom Killer, a brutal, hooded menace who terrorized the town just after World War II. The real perpetrator’s similarities to the Zodiac Killer are still discussed today. Pierce’s film prefigured the dawn of the slasher movie craze spurred by John Carpenter’s Halloween (1978), as well as the onslaught of horror vehicles about masked slayers.

In 1976, Pierce rose to prominence again when he delivered another based-on-fact drive-in horror hit. The Town That Dreaded Sundown recounted Texarkana’s most infamous cold-case, that of the Phantom Killer, a brutal, hooded menace who terrorized the town just after World War II. The real perpetrator’s similarities to the Zodiac Killer are still discussed today. Pierce’s film prefigured the dawn of the slasher movie craze spurred by John Carpenter’s Halloween (1978), as well as the onslaught of horror vehicles about masked slayers.

Though financially successful, the film opened up old wounds afresh in Texarkana. “During filming, he started getting death threats,” says Squitiero. “It became such a problem that we moved to Texas for a long time as a result. My mother moved us into a fortress because she was worried about our safety. Things cooled down in Texarkana, so the Little Rock Film Festival now gives their Charles B. Pierce Award for best film made in Arkansas.”

Due in part to the modest commercial success of The Town That Dreaded Sundown (which was remade in 2014), Samuel Z. Arkoff offered Pierce a three-picture deal at American International Pictures. Under this contact, he made The Norseman (1978), and The Evictors (1979). The former, a critically savaged box-office flop, starred Lee Majors as a Viking warrior, while the latter starred Vic Morrow and Jessica Harper (just after her starring turn in Dario Argento’s masterwork Suspiria). The Evictors, shot in Louisiana and also based on alleged fact, completes a “trilogy of terror” that commenced with The Legend of Boggy Creek.

To his dying day, his AIP days stirred bitter memories. Squitiero recalls her father’s rancor: “I remember him getting so frustrated that he would carry on and say, ‘No one will ever tell me what I’m doing on my motion picture. It’s my motion picture!’ It was always a ‘motion picture’ with him, rarely a ‘film’ and certainly never a ‘movie.’ He hated the word ‘movie.’”

In the eighties, Pierce suffered his career’s biggest embarrassment, a failed sequel to The Legend of Boggy Creek that was later parodied on Mystery Science Theater 3000. Although he was hesitant, producers had been hungry for one for well over a decade. He went on record with Tulsa World saying, “I really didn’t want to do Boggy Creek II. I think it’s probably my worst picture. This time, I spent almost as much time on the creature suit as I did on the film itself.” The director also appears as lead actor in Boggy Creek II: And the Legend Continues (1984); in some of his previous films, he popped up in colorful walk-on roles or supporting parts.

On Hawken’s Breed (1987), which starred Peter Fonda, he was denied final cut. “Hawken’s Breed was the product of a very unhappy joint financial venture,” says Squitiero. “I think that experience frustrated him more than the problems he had on the AIP pictures. Really, he was happiest when he was completely independent. He became a bit of a recluse after Hawken’s Breed. He wanted to slow down, so he spent his time fishing, painting, drawing, taking still photographs.”

In the late nineties, he returned briefly to his cinematic vocation with two features, the family drama Renfroe’s Christmas (1997) and the mountain-man saga Chasing the Wind (1998). Neither film saw wide release; Chasing the Wind has completely fallen out of circulation.

His final years, leading up to his 2010 death, were ones spent thinking and talking about the next film projects. One journalist, who enjoyed a telephone relationship with him towards the end, recalls: “He was a very sincere person, and always got to the meat of what he wanted to tell you, no BS. Despite what fate had handed him, he was not bitter…at least beyond what anyone who has ever worked in Hollywood is, by default. He had purchased an early HD video camera and was shooting beautiful nature footage for a project that never got completed. And he was considering doing a remake of The Legend of Boggy Creek.”

Squitiero paints a portrait of her father: “He was colorful, perhaps the best raconteur who ever lived. No one could recount a story like he could. He’d paint a really clear, vivid picture in your mind. And the stories of the making of his films are often just as wild and action-packed as the films themselves. And he had all the wonderment of a child.” A particular tale of an out-of-control buffalo on the set of Winterhawk is a favorite of hers.

If a single sequence in one of Charles B. Pierce’s films were to function as an x-ray of his artistic soul, the deeply touching runaway horse sequence in The Winds of Autumn best defines his unmistakable humanity.

In the sequence, twelve-year-old Quaker boy Joel (played by Pierce’s own son, Chuck Pierce, Jr.) treks alone through the wilderness. As he begins to ascend a mountain on horseback, a snowfall begins to dust the landscape. When Joel briefly dismounts the horse, the animal gets spooked and runs off and leaves the boy freezing, hungry, and even more desperate. He walks for miles through the cold, as the thickening frost and bitter winds beat against him. Suddenly, just ahead of him, an Indian wrapped in furs appears astride his own horse, clearly awaiting his arrival. Joel’s runaway horse stands beside him. The boy is dumbstruck and relieved as the Indian leaves two rabbit carcasses on the horse’s saddle and rides off. The boy leans into the animal’s mane for a quick prayer of thanksgiving before wearily mounting him again to continue his trek.

Here, Pierce’s aptitude for purely visual storytelling, composition and pacing, along with an acute sense of editorial syntax, augments what would have naturally been an effective and affecting sequence as written. Its heart and emotional resonance stems from a technical mastery.

Despite being a longtime DGA member, he was not honored at the Oscar ceremony’s annual “In Memoriam” tribute (in the same year Farrah Fawcett was likewise ignored). In Arkansas, June 16 was declared “Charles B. Pierce Day” by the two Texarkana mayors, Bob Brueggeman (of the Texas section) and Wayne Smith (of the Arkansas section). Today, director Jeff Nichols (Take Shelter, Mud, Loving) has picked up the mantle of Charles B. Pierce in regularly returning to make feature films in his native Arkansas.

So, how can an independent filmmaker of today follow the example of Charles B. Pierce, who often released more than one feature per year, and in a region that lacked the infrastructure for such endeavors?

The good news is that, today, with access to the digital tools, making regional films of value is a goal that is much easier to realize. In the mad dash to the east and west coast, it is perhaps easy for people to forget those stories that emerge from the perceived “void” where the “purple mountains majesties” and “amber waves of grain” dwell.

Regional filmmakers have greater capability to build bridges of empathy, and to achieve the art of the possible as Charles B. Pierce knew it to be. In the film world, people often most admire those who make “it” happen, whatever “it” happens to be. The purpose of this piece is not simply to draw deserved attention to a departed artist’s neglected body of work, but also to claim his life as a testament to ingenuity and passion for the craft.