Back to selection

Back to selection

My Journey Through French Cinema: Personal Canon-Building with Bertrand Tavernier

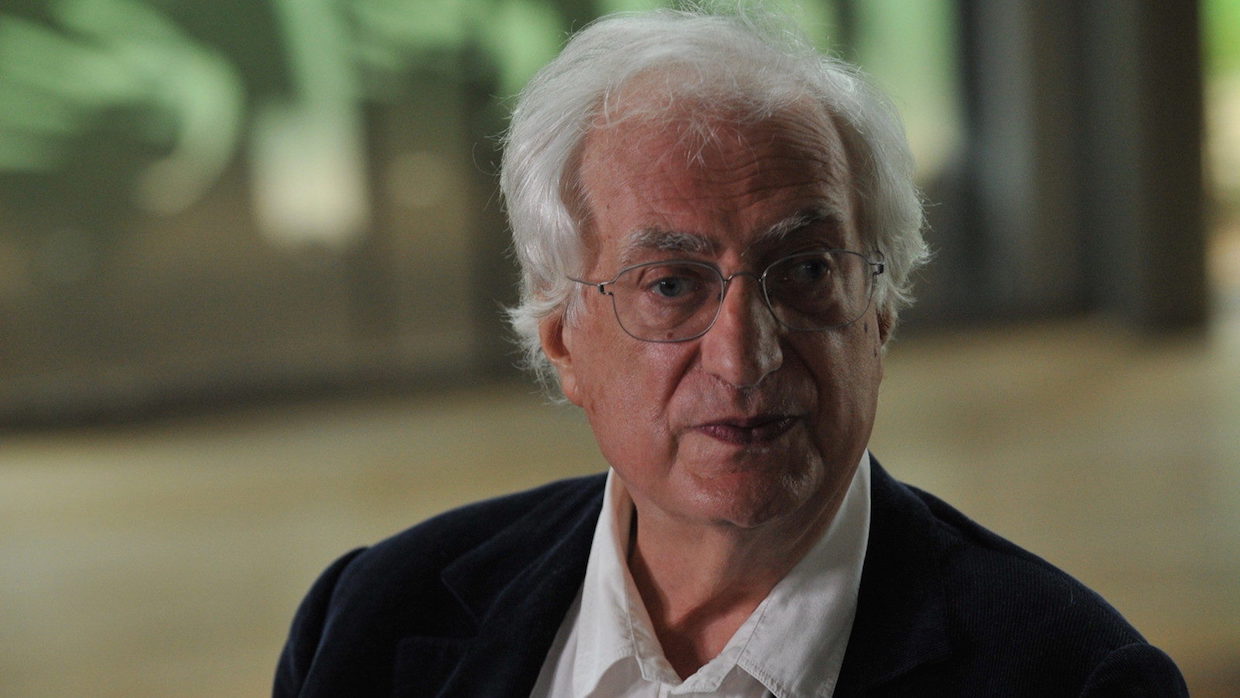

Bertrand Tavernier in My Journey Through French Cinema

Bertrand Tavernier in My Journey Through French Cinema Names you won’t hear in Bertrand Tavernier’s personal history of French cinema: Abel Gance, Marcel Pagnol, Sacha Guitry, Alain Resnais, Philippe Garrel. Don’t expect to hear about any directors who got started after the ’60s either: Tavernier begins with a solid overview of the glories of Jacques Becker, the first director to make an impression on him (“At age six, I could have chosen worse”) and ends with an equally lengthy tribute to Claude Sautet — along with Jean-Pierre Melville, one of his two professional fairy godmother gateways to the production side of French cinema. There is, to be sure, plenty of time devoted to Renoir and Melville, and a good deal on Godard (Tavernier was his press agent); this is, nonetheless, a thoroughly personal overview of the filmmakers Tavernier watched/worked for until he started making his own films with 1974’s The Clockmaker — thus far and no further.

You will repeatedly hear the name of one post-’60s director, Quentin Tarantino. This makes a kind of sense: both Tarantino and Tavernier are aesthetically-quasi-omniverous proponents of personal canons whose films arguably transcend the sum of their influences. Granted, that’s a tricky, potentially over-dismissive argument: I’ll cop to not being overwhelmingly familiar with the pre-New Wave filmmakers Tavernier spends the majority of his running time admiring, though I’d seen more of the selected titles than I’d expected, mostly at idle weekend afternoons taking chances on MoMA rep programming. I’ll cheerfully stump for Becker’s Modigliani of Montparnasse or Claude Autant-Lara’s Four Bags Full, less so Julien Duvivier’s Un Carnet de Bal.

This is all a matter of taste; one viewer’s forgettable middlebrow is another’s exquisitely fine-tuned classicism. Tavernier’s picks are refreshingly unconcerned with internationally canonical movies viewers outside of France might reasonably be expected to have knowledge via regular theatrical reissues or home video access. This is undeniably edifying, even if I’m more interested in boosts for such previously-unknown-to-me quantities as Jean Sacha and select Eddie Constantine vehicles than other bits of advocacy. It’s bold, and, in Tavernier’s unabashed admission, “in a spirit of provocation” to stop for a devil’s advocate reconsideration of late-period Marcel Carné via stultifying excerpts from 1971’s Les Assassins de l’ordre, but I remained unconvinced of the need to dive down that deep cut rabbit-hole. While his analysis of Renoir’s staging strategies is lucid aces, often Tavernier speaks in vague ways of various directors’ virtues (force, vigor, clarity), failing to translate his enthusiasm into something I can perceive myself; he’s on much more solid ground delving into the collaborative production particulars of various figures, as in clarifying the back-and-forth casting et al. disputes between Carné and Jacques Prevert. Much time is spent on composers as well: as someone who makes films himself, Tavernier has a much keener sense of the pragmatics behind each films than the average production-unfamiliar critic (and, granted, he has other trump cards like gossip from conversations with e.g. Jean Gabin).

Tavernier’s performing advocacy on behalf of a strand of French cinema largely thrown out of critical respectability by the polemicists of the New Wave. Refreshingly, he spends zero time rehashing the rise of Cahiers and the revolt against “cinéma du papa,” but the context is clear (assuming you have it already, as this isn’t an entry-level primer): at one point, he expresses regret for dissing Yves Allegret in a piece of youthful advocacy for a work dismissed as a B-movie (“better B for Boetticher than A for Allegret”). I found myself oft-unconvinced while remaining simultaneously sympathetic to the project’s broader scope. This advocacy isn’t just talk on Tavernier’s part: the process of assembling the archival footage led in some cases to active restoration of the titles under consideration, which is all to the good. If I found myself often unable to perceive the connection between some of the seemingly stodgier titles on display and Tavernier’s own stellar work — notable in particular for the speed of both its editing and camera movements, and a general penchant for the unostentatiously vigorous — it’s useful to consider the ways we’re all shaped as viewers and (not me!) makers. It’s a subject Tavernier’s spent literally his whole life thinking about, and if the film’s block-by-block lumpiness has the same one-thing-after-another consistency as a biopic which dutifully follows a subject’s life with no sense of dramatic sculpting, that makes sense: his cinema is his life. And anyway, watching a deluge of clips is always fun.

My Journey Through French Cinema opens in limited release on Friday; listings are here. Quad Cinema’s Tavernier retrospective begins tonight.