Back to selection

Back to selection

Twin Peaks: A Language More Powerful Than Words

Twin Peaks: The Return

Twin Peaks: The Return Of all the remarkable aspects of Twin Peaks: The Return, perhaps the strangest is not something that is present, but something that’s absent: the utter lack of any recognizable psychology. Characters simply aren’t motivated by the familiar psychological archetypes and cliches that underpin almost all narrative entertainment, especially series-based television. It’s not so much that the plot is inscrutable or resistant to interpretation, but that characters react to what’s happening around them in ways that look and feel familiar, but which betray little if anything of what’s going on in their heads. As opposed to shows like House of Cards or Westworld, where characters’ motivations and pathologies (“You have no idea what it means to have nothing! I have had to fight for everything my entire life!” Kevin Spacey’s Frank Underwood declares in House of Cards‘ season 4) are made clear through exposition, Twin Peaks works in a much different register, relying on something closer to the expressionism of silent cinema, when acting was largely gestural.

In fact, much of Twin Peaks plays like silent film, or film whose only sound is music and noise, as there are long stretches that feature either no dialogue or only intermittent words, such as the opening of part 3 featuring Cooper and Naido, the eyeless woman. Nearly 12 minutes pass with no dialogue, just a few utterances by Cooper. The scene — tinted and flickering — plays like a fragile document from pre-1910 Georges Méliès or D.W. Griffith. And although considerably shorter at approximately two-minutes, the floor-sweeping scene in The Roadhouse near the end of part 7 is just as radical: a Lumière brothers single take depicting an everyday activity — a mini-documentary, of sorts — about sweeping. Working outside the constraints of exposition or characters-talking-to-each other-about-what-they-are-thinking-and-how-they-are-feeling, Lynch is free to pursue a different sort of visual logic, one that allows for a fuller expression of linear time. And the really interesting thing about the long takes in Twin Peaks is how unmotivated they are by what’s happening during them plot-wise. These aren’t long takes used in the traditional cinematic sense, used to punctuate a typically bravura or lyrical sequence, but rather to highlight the everyday, the banal, the ordinary, such as Dougie’s walks into and out of the Lucky 7 insurance building.

Part 9 continues this pattern with extended shots that balance so delicately between comedy and sadness, as in the shot where Diane goes outside to the morgue’s steps for a smoke and is joined by Gordon and Tammy. In silence Diane smokes as Gordon watches with fascination and desire. The unbroken shot lasts for over two minutes with only a few lines exchanged at the end. The communication between Diane and Gordon is wordless, silent signals being exchanged that are grounded in their deep and long-lasting relationship, perhaps echoing the long history between Dern and Lynch. On first viewing it’s a puzzling shot, and on subsequent viewings it plays as an extended piece of static physical comedy. The same holds true for the extended Las Vegas Police Department sequence which extends to just under nine minutes, shifting between something approaching slapstick comedy amongst the detectives, and real feeling and pathos with Bushnell and Dougie. Within the sequence there is one two-minute scene in particular featuring Dougie and Janey-E as Dougie becomes fixated on the American flag which leads his eyes to wander, eventually, to a wall outlet, the sign of his rebirth into the world.

In his 1940 essay “Achievement,” Sergei Eisenstein commented on the radical techniques developed by James Joyce, whom he credits (along with Charles Dickens) as profoundly influencing the grammar of cinema. Joyce “unfolds the display of events simultaneously with the particular manner in which these events pass through the consciousness… of his characters. The effect at times is astounding, but the price paid is the entire dissolution of the very foundation of literary diction, the entire decomposition of literary method itself.” Although stream of consciousness as a literary method has become so canonized as to lose its shock value, it was so fresh and disorienting in the 1920s and 30s, with those long, uncurling sentences paging on and on in the works of Joyce, Virginia Woolf, Faulkner and others. (And what strange, influential works appeared in 1922, the year of Ulysses, including F.W. Murnau’s Nosferatu and the Swedish witchcraft film Häxan, whose black-and-white tableaus find weird echoes in Twin Peaks part 8.) Although cinema has always had its avant-garde, it seems to have stalled permanently in the realist mode, which makes sense as it was invented in the era of the realist novel. Even genre films that are not realist in the sense of content (i.e., superhero films or science fiction fantasy films) are realist in the sense that they rely on what have come to be the accumulated, refined, customary cinematic tools for depicting even unrealistic stories realistically via shot/reverse shot, establishing shots, close-ups, focused sound and a host of other techniques which grossly distort perceived reality in order to make it feel “real.”

Which brings us back to the absence of familiar, recognizable patterns of psychology in Twin Peaks. Lynch has spoken often about how everything begins with an idea. In a recent interview with Variety, he noted that “an idea holds everything… it has sound, it has image, it has a mood, and it even has an indication of wardrobe, and knowing a character, or the way they speak, the words they say.” Characters work in the service of ideas and since — in Lynch’s way of seeing things — ideas come from “out there” and are caught like fish, it would make sense that his characters, while they are of course psychological creatures, are motivated and governed by other, larger forces which may have very little to do with human need or desire. It’s not that his characters don’t feel (scenes like Diane confronting Cooper’s doppelganger in prison are full of deep feeling and anxiety) but that there’s very little exposition or overt dialogue to telegraph to the viewer the nature of these feelings, which often seem to come from deep reservoirs of mystery.

Even though it’s been much commented on, Lynch’s roots as a painter (both informally and formally, as he enrolled after high school at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston and later at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts) remain at the heart of films, which he began making because, he has said, he wanted to see paintings move. But paintings can’t talk. When we look into at the work of the painter Francis Bacon — whom Lynch has cited as an inspiration — whatever human figures there are do not move. They do not speak. In “Two Figures at a Window” (1953) we are confronted with silence. There is no presentation of psychology, just our own interpretation which is, weirdly and democratically, a reflection of our own psychology. In the face of a painting we are confronted with our own inner selves. What we think we see and how we interpret and make sense of what we see tells us more about ourselves than the painting or the intentions of its maker.

In his book David Lynch: The Man from Another Place, Dennis Lim notes that “in the speech patterns of Lynch’s films, with their gnomic pronouncements and recurring mantras, the impression is of language used less for meaning than for sound.” The long stretches of wordlessness in Twin Peaks work in the opposite way that most TV operates, where dialogue-free montage is used to convey a pronounced sense of mood or atmosphere. This is reversed in Twin Peaks, as dialogue conveys very little narrative information. Dougie’s trouble with language plays sweetly and sometimes comically, and yet his verbal responses to those around him distill what they say down an essential, core meaning. In part 6, Bushnell Mullins exasperated by Dougie’s seemingly childish doodlings on the suspect insurance files, tells him, “I’m thinking you might need some good professional help, Dougie,” to which Dougie responds “Help, Dougie.”

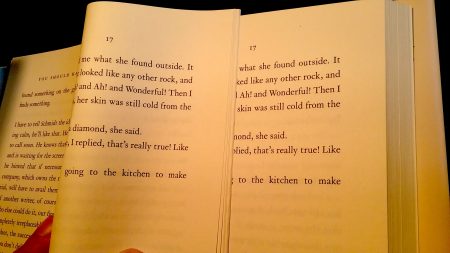

Side note: I don’t know if this has happened to you or not, but sometimes after I’ve watched an episode of Twin Peaks, something strange happens. Either that or I’m just more receptive to weirdness, because I’d been reading the excellent new bizarre novel by Daniel Kehlmann, You Should Have Left, which features an unreliable narrator keeping a journal. So when I picked the book up again after watching part 8 and started reading where I had left off, I figured I’d made a mistake in bookmarking because what I was reading sounded familiar. Which, in fact, it was. Five pages from the novel are repeated, so that the pagination goes pp. 1-24, 9-17, and then 18 to the end. This could be simply mis-pagination, but it could also be deliberate. In any case it has made a strange novel even stranger and more memorable, and — against all reason — I thank Twin Peaks for that. And for reintroducing a sense of wonder into our degraded world.