Back to selection

Back to selection

Shutter Angles

Conversations with DPs, directors and below-the-line crew by Matt Mulcahey

DP Andrew Droz Palermo on A Ghost Story, Shooting 1.33 and That Pie Shot

Andrew Droz Palermo on the set of A Ghost Story (Photo by Bret Curry)

Andrew Droz Palermo on the set of A Ghost Story (Photo by Bret Curry) The polarity between director David Lowery’s $65 million Disney film Pete’s Dragon and the micro-budgeted A Ghost Story has been noted repeatedly in reviews and profiles. But the man behind the camera on A Ghost Story has a unique career trajectory of his own.

Cinematographer Andrew Droz Palermo made his feature debut with Adam Wingard’s tone-mashing home invasion horror flick You’re Next in 2011. He followed that by co-directing a documentary (Rich Hill, an affecting character study of Missouri teens living in poverty) and a narrative feature (One and Two). Palermo is back in director of photography mode on A Ghost Story, which finds a deceased musician (Casey Affleck) trapped in his former house — and a boxy 1.33 aspect ratio. Palermo spoke to Filmmaker about pulling off Affleck’s bed sheet ghost costume, almost prematurely bulldozing the main location and that epic Rooney Mara pie scene.

Filmmaker: Tell me a little about the script for A Ghost Story. I understand the shooting version was roughly 40 pages and David Lowery included very specific details such as the length of certain shots.

Palermo: The first version of the script that I got was about 25 pages and – though there are some key differences – it’s very much the movie that you see. Some shot lengths and even the aspect ratio were declared in the script. So the intention was clear from the beginning. For example there was a scene where Rooney [listens to one of Affleck’s songs] on headphones and the script said that we would not hear the music that she’s hearing, but instead we would watch her listening to a song for 3 ½ minutes. That scene changed in the final edit, but those sorts of details were spelled out. Or when the ghost gets off of the gurney, the script said “The camera holds for an impossibly long time.” (laughs)

Filmmaker: Did you and Lowery have any references for the long, often static takes in the first section of the film?

Palermo: A lot of our touchpoints were from Asian cinema – such as Stray Dogs director Tsai Ming-liang and some Taiwanese New Wave filmmakers like Apichatpong Weerasethakul, especially his Uncle Boonmee, which is also very slow and deliberate but has these really fanciful elements.

Filmmaker: No one is divulging the film’s exact budget at this point, but Lowery has said that the cost of the entire movie was less than one day of shooting on Pete’s Dragon. I’ve seen stills from A Ghost Story with long dolly track, Steadicam, and a MoVI and you were able to shoot on an Alexa Mini — so it’s not like you were working with bare bones tools. But was there anything that you really wanted that you couldn’t afford?

Palermo: Not particularly. My lighting package and my camera package were extremely small. We struck an amazing deal with Panavision and that’s due to Panavision being supportive of mine and David’s careers, and also knowing that it’s sort of an investment that we will continue to bring them business.

There was an early conversation where I was interested in using anamorphic lenses, but then cropping the image to a 4:3 (aspect ratio) because I really wanted that shallow depth of field that you can get from anamorphic. I just felt like that would be something that people hadn’t really seen – we’d have this shallow focus even in the wide shots. We just couldn’t afford a nice set of anamorphics. But I’m really happy with the Panavision Super Speeds and Ultra Speeds that I ended up with and thought they performed really well.

Filmmaker: You had a single, mixed set of lenses, right? So your 24mm might be a Super Speed and then the 50mm might be an Ultra Speed.

Palermo: Exactly. It was a mixture of Ultra and Super and there’s not much perceptible difference between them. The 50mm Ultra Speed that I had opened up to a T1.0 and that’s astoundingly fast. We also had a couple of Panavision Primo zooms with us for a lot of the shoot as well, but not all of it.

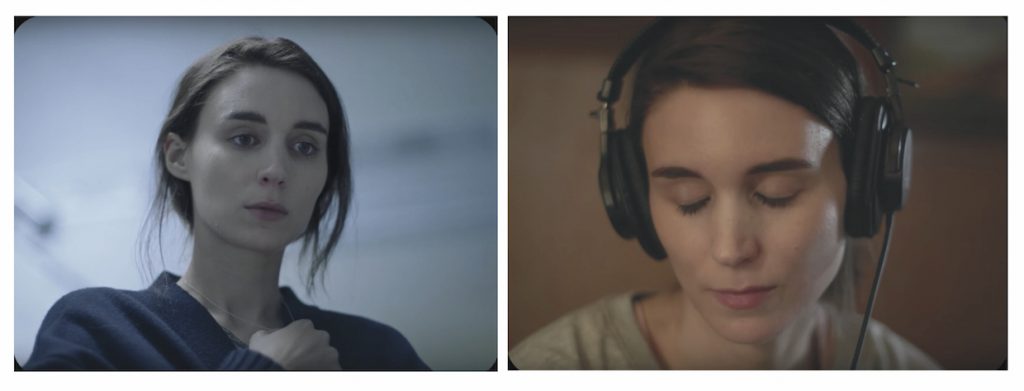

(Above) A pair of Rooney Mara close-ups shot at a stop of T1.0.

Filmmaker: Sometimes people say you shouldn’t shoot those older lenses wide open because you don’t get the best image quality that the lens is capable of. Were you able to shoot those lenses wide open?

Palermo: Well, it depends on what the subject is. It only becomes apparent when you have really hard edges in the frame — like shooting architecture, for instance. If you’re shooting something like that it becomes more noticeable that the lens is really falling apart, because the chromatic aberration starts to shift on the hard lines and the corners of the frame can get softer and vignette. Some of my favorite stuff in the film was actually shot at a T1.0, but those shots were just faces and you can get away with it. Rooney listening to her headphones and then Rooney looking at Casey’s body on the gurney were both shot at a T1.0.

Filmmaker: You opted for 4:3 mode on the Alexa Mini – so you were locked into that 1.33 aspect ratio from the beginning. There was no turning back.

Palermo: We had some other cameras out occasionally — like Alexa Classics or even a Red — and those images were shot in [wider aspect ratios] and we would kind of wonder, “Did we make a horrible mistake? These wider frames look amazing.” (laughs) But I’m happy that we painted ourselves into that corner and had to stick to our guns.

(Above) An early version of the ghost was used during a test day at a construction site and ultimately made its way into the final film.

Filmmaker: When you were shooting tests for the ghost’s costume, what was the most disastrous version?

Palermo: It’s actually in the movie and it’s one of my favorite shots. It’s when the ghost is in what we called “the pit,” which was this big construction site. We shot that on a test day, but we also knew those shots would end up in the movie because that was the only day we could get into that location.

That early version of the ghost had an extremely wide nose that didn’t really feel like a nose. The sheet was also very transparent so you could really see the form underneath it, which sometimes was kind of cool but often we didn’t want it to look like there was a human body under there. Costume designer Annell Brodeur worked really hard to give the ghost more of a form. She built up sort of a petticoat underneath the sheet and made this soft helmet that shaped the face. I think she did really great work and I’m so happy she pushed it past that first version.

Filmmaker: You shot some of the ghost footage at 33 frames per second (fps) – which is slight slow motion. How did you land on that number?

Palermo: That’s something that [Pete’s Dragon cinematographer] Bojan Bazelli suggested to David on that film to punctuate certain things, and we found with the ghost that 33 frames per second was perfect. It shaved off any remaining bit of humanity in the way he walked and the way he moved. It made him glide a little more. We toyed around with ways in which we could make him kind of float. At one point we joked, “Let’s put him on a hoverboard so he can just roll around and not have to use his feet.” (laughs) But there are many scenes where he’s shot at 23.98 because other characters are moving in the frame. For those shots the ghost typically wasn’t doing big moves. If he was just standing there, we could shoot him at 23.98.

Filmmaker: I read that you would sometimes shoot the ghost at 33 fps and then shoot another plate of the same frame with an actor at 23.98 and composite the two together.

Palermo: The compositing work wasn’t really about the ghost’s motion. A good example of how we used [that technique] is when Rooney eats the pie. There’s no reason the ghost would need to be in that frame for that entire time — and if he was in the frame and something happened to his costume or he didn’t do something right, he would’ve spoiled a really long take. So we divided that frame right down the middle, did a take with Rooney eating the pie at 23.98, and then afterward threw the ghost in and shot a plate of him also at 23.98. I don’t think there are any instances of those plates being shot at different frame rates.

Filmmaker: What was the shooting schedule like?

Palermo: We shot something like 16 days of principal with Casey and Rooney. Then we went away and came back and did another 10 or so days — I forget exactly how many. Then finally I shot an additional two or three days before we went down to Austin to color.

Filmmaker: What types of things were you shooting during those two pick-up sessions?

Palermo: All kinds of stuff. It was mostly new material rather than reshoots. In the first round of pickups we were shooting a lot of the ghost on greenscreen so that we could toss him into shots that he wasn’t originally planned to be in. For example, the script started with a ten-page conversation between Casey and Rooney and ultimately that got chopped up in the edit. The material from that conversation is mainly at the end of the movie now, which meant the ghost needed to be present.

We also shot the destruction of the house during the pickups because we knew if we destroyed the house in principal photography there would be no opportunity to shoot there again.

Filmmaker: Smart move.

Palermo: Honestly, as simple as that idea sounds, it occurred to me very late one night driving home from set. I was like, “Guys, we have to call off the demolition. Let’s give David some time to figure out what the movie is in the edit and see what we might need to come back and get.”

Filmmaker: Since you brought up the pie scene, let’s dig into that. It’s two very long shots of Rooney Mara taking down almost an entire pie in real time — and you didn’t do any coverage to be able to cut that down.

Palermo: It was in the script that way. On the day, Rooney suggested that she would probably sit down on the ground to eat the pie. So I put a lens on the viewfinder and ended up in a corner that I thought would be the best spot for the camera. After shooting the first half of the scene — the piece where Rooney is standing — there was a lot of discussion and conversation about the pie. Eventually I had to push us forward and say “We really need to shoot right now,” because I knew there was this sunlight that was going to come through the trees and hit behind Rooney’s head at a certain time of day and we had to start shooting so we didn’t miss it.

(Above) A shot from A Ghost Story (left) and a similar image snapped during a location scout (right) by cinematographer Andrew Droz Palermo.

Filmmaker: Let’s talk through a few frames, starting with this shot of Affleck on the gurney that you mentioned earlier. After Mara exits frame, the camera sits motionless for what feels like an eternity before Affleck’s “ghost” sits up.

Palermo: This was a space that we scouted heavily and I took a lot of photos while we were there. I actually have a photo of David and one of the producers, Toby Halbrooks, staged in this exact position. So this shot was already something we were thinking of well in advance. It was a very considered frame, because we knew it was going to be an extremely long take. There’s actually some stuff at the end of the shot that was cut that was very funny but perhaps a little too different from the rest of the movie. Casey got up [covered in the sheet] and walked across the room into close-up and then tripped and fell out of frame. Then he stood up again and the eye [holes] were now there in the sheet. It was a little goofier than the rest of the film, but it was fun to stage and to watch Casey walk across the room blind under the sheet.

Filmmaker: During a party thrown by one of the home’s future inhabitants, a reveler (Will Oldham) breaks into an extended monologue about the meaninglessness of existence on a planet that will eventually be subsumed by the sun.

Palermo: In an ideal world we would’ve loved to have done a long take for this — and we talked a little about Werckmeister Harmonies, the Béla Tarr film, and the way that film opens with a monologue from a character about the solar system. Will was so great in that scene. He nailed that monologue every time. He never needed a line fed to him. He came incredibly prepared. But it’s such a long monologue, and there’s so many other characters involved and we had all these extras, so we ultimately decided to cover it rather traditionally with mediums and close-ups and profiles and reverses. We had two cameras working on that. Largely I just lit it from straight above and then there’s that one kitchenette light [over Will’s right shoulder in this frame] that changes color depending on who’s living in the house. In this shot it has a half-pink party gel on it. With the Latino family it had a little bit of CTB [Color Temperature Blue] and then when it’s Casey and Rooney’s house, it’s CTO [Color Temperature Orange].

Filmmaker: Your hero lights for the show were the LiteGear LiteMats. Is that what you used here – a LiteMat armed out over Will’s head for a toplight key?

Palermo: That’s right. We put one directly overhead to emulate this bare bulb that you see in the wide shot of this scene.

(Above) A VFX shot courtesy of Weta Workshop (The Lord of the Rings, Avatar). Director David Lowery talked the New Zealand-based company into helping out on A Ghost Story following their collaboration on Pete’s Dragon.

Filmmaker: This last frame takes place when the timeline jumps ahead and the ghost stands atop a high rise staring out at a futuristic cityscape.

Palermo: This shot is entirely greenscreen. There’s not a real element in this shot with the exception of the ghost. The camera move is also real – I was up really high in a greenscreen studio and I tilted down to a green floor and then back up to the ghost, who was just standing there on a platform we built with apple box steps. We were also blowing really big fans at him to give his costume some play. Weta did fantastic work. They really brought a lot of texture into those windows to make it feel like a natural cityscape is around him.