Back to selection

Back to selection

“If You Were a Real Filmmaker, You’d Have a Fancier Camera”: Oren Jacoby on Shadowman

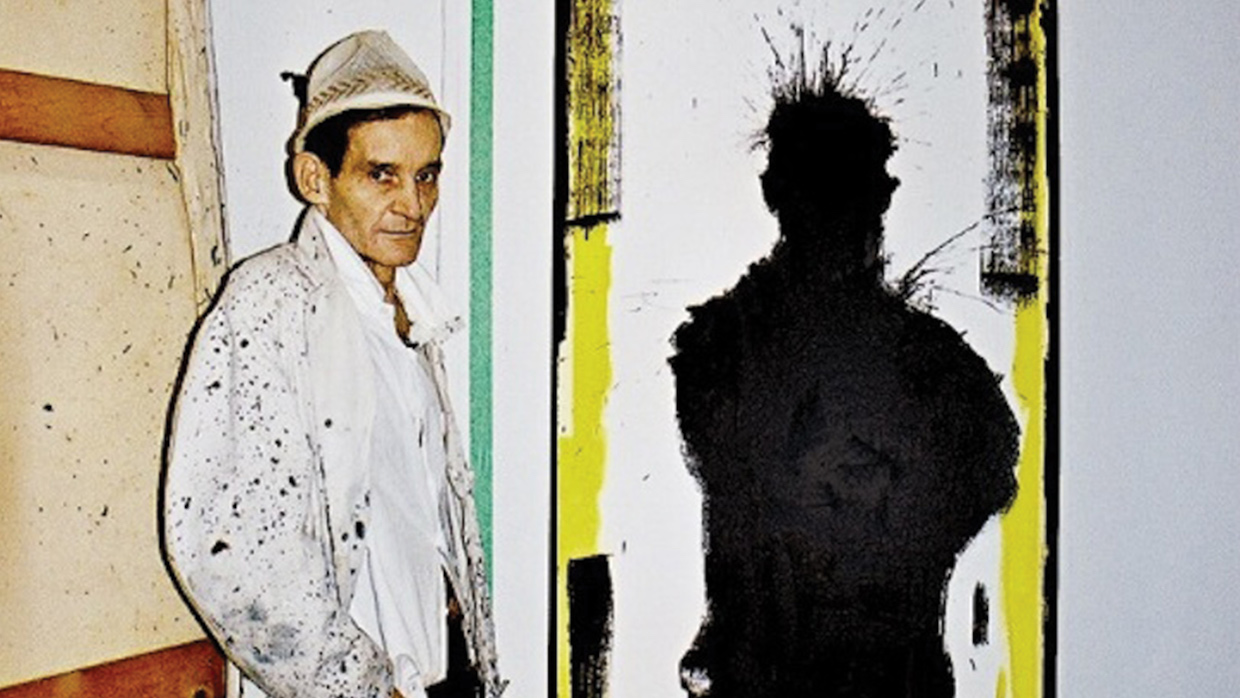

Richard Hambleton in Shadowman

Richard Hambleton in Shadowman One of the most celebrated street artists of the 1980s, Richard Hambleton created a collection of equally eccentric and harrowing work that decorated the walls, alleyways and sidewalks of New York City. Along with Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat, Hambleton was an unrivaled challenging artist and, as his contemporaries tragically died before middle age, one of its remaining beacons of inspiration. While known for his “murder art” — chalk outlines of fictitious crime scenes splattered with red paint resembling blood — and his Marlboro Man paintings crafted from a thick tar-like substance, Hambleton’s most iconic pieces serve as the namesake of Oren Jacoby’s new documentary in theaters this week.

Debuting in the summer of 1980, Hambleton’s Shadowman wall art, mysteriously anthropomorphic Rorschach tests that popped up in every crevice of New York and trickled up from the streets to the art galleries; fame (and fans, including modern day U.K. pop artist Banksy) followed. And while the subsequent rise of AIDS and a 1987 stock market crash attributed to the demise of this particular chapter in street art, Hambleton’s biggest obstacle was that he didn’t dissolve along with it. Catching up with the artist today, living on Orchard Street and re-reading every newspaper clipping covering his work, Hambleton is still difficult to deal with, still stressed, still needing of more time and still brilliant. As the documentary opens, Hambleton is to have a fancy career retrospective shortly, and he demands every last second to get it right.

In advance of the documentary’s opening at the Quad Cinema this Friday, I spoke with Jacoby about representing the New York arts scene of the 1980s, the aesthetic appeal of celluloid wear-and-tear, getting Hambleton comfortable in front of the camera and how the legacy of his subject lives on in today’s prolific street artists.

Filmmaker: How long has a nonfiction story about Richard Hambleton’s life been percolating? In terms of newly shot footage, your material begins in 2009 in preparation for a career retrospective of the artist’s work. Was that your way in to this story?

Jacoby: I started the story in 2009. There hadn’t been one in the works before I met Richard and decided to make a film. Other people had shot footage of Richard, which we were very lucky to discover and include in the documentary, but that was it.

Filmmaker: What was that footage?

Jacoby: The earliest material from the late 1970s and early ’80s comes from two films made by art students who knew Richard’s work. They got to know him and were able to follow him in action, documenting what was happening at the moment.

I first became aware of Richard when I was living on the Lower East Side — I guess you could say the edge of Tribeca — at the end of 1979 and 1980. I started to notice those shadows and some of his other conceptual works that were popping up around the city. I became interested in the artist but didn’t know his name and, for a long time, didn’t even know that each of the works were done by the same person. I only realized that thirty years later when I was introduced to Richard by Hank O’Neal, a still photographer, who had been documenting a lot of his work. Hank’s coverage dates back to Richard’s arrival to New York in 1979, and he became an important part of my documentary.

Filmmaker: When we see art dealers Vladimir Restoin Roitfeld and Andy Valmorbida working in Richard’s Orchard Street studio to “get his shit in order” for an upcoming, ultra fancy retrospective presented by Giorgio Armani, Richard is highly stressed, sleep-deprived and suffering from skin cancer that he refuses to treat. How did he feel about being in front of your camera? Was he on board from the very beginning?

Jacoby: It’s kind of a funny story, as I wasn’t sure at first. The first time I went in there, I engaged with Richard directly, talking to him and asking questions. A lot of material in the film, where Richard is at his most outgoing in those early scenes, consisted of me asking a lot of stuff on one of my early visits. He was engaging and outgoing with me because I remembered the work and I reflected on my experience of seeing it.

After that visit, I was shooting everything myself, sometimes with Andy and Vlad, sometimes just with Andy (and sometimes without both), and for some reason, Richard kind of ignored me. I couldn’t figure out why. I tried to follow what I heard from other good verité cameramen — which I don’t pretend to be in the slightest — and I’ve learned my lessons from some good ones, including Ricky Leacock, who I was lucky to work with early in my career, and Bob Richman, whose been a DP on a number of my films. They taught me not to shove my way in. You work from far away, you work slowly from the sides and from behind the subject. You don’t try to intervene. You let the subject get used to you being there. I tried to follow that, but still couldn’t understand why Richard wouldn’t notice me nor pay any attention to the fact that I was there.

I finally bought into the idea that what was happening between him and Andy and Vlad (and his former girlfriend Mette Madsen) was more interesting than the fact that I was filming. And hey, if a character isn’t doing something more interesting than just being in front of your camera, then you should put your camera away anyway.

I had this funny encounter with Richard after the film was finished. We went to talk one final time, meeting on the roof of this hotel he was staying at in Little Italy. I told him that the film was completed and that it was going to be in the Tribeca Film Festival. And while he was excited that the film was done, he said that he never believed I was going to finish it because I had such a crummy camera. “If you were a real filmmaker, you’d have a fancier camera,” he told me. Maybe that’s why he didn’t pay any attention to me. He figured “Well, he’ll never finish the movie anyway, so it doesn’t matter.” He didn’t take it seriously.

Filmmaker: I believe three cameramen, including yourself, are credited on the film. Were you responsible for all of the Orchard Street footage?

Jacoby: Pretty much. There was one shoot that Bob Richman filmed, but I filmed all the others, sometimes with help from Elgin Smith, my associate at the time, who did the sound and, if something happened where I couldn’t position myself, him being taller allowed him to shoot as well.

Filmmaker: How did Motto Pictures come aboard the project?

Jacoby: They’ve been amazing partners. I guess it was just a little over a year ago that I was wondering how I was ever going to finish this film. I was discouraged. I tried to raise money, tried to find distribution people who would sign on, approached other distributors I had worked with previously, etc. Some people liked the film and offered to go out and raise money for it, but nobody could deliver anything. I didn’t have the money I needed to finish the film.

I was lucky enough to get into IFP Week’s Spotlight on Documentaries program and scheduled a bunch of meetings for the project. One of those meetings was with Motto Pictures’ Julie Goldman, Christopher Clements and Carolyn Hepburn. I knew Julie from years prior (we tried to work together on several projects that just didn’t work out) and had thought of Motto as an ideal partner to help get the film a bigger profile, for people to take it seriously. I think I showed them the trailer and the rough cut, and they liked it and said they’d try to help get the film to the finish line. Partly through their efforts, things started to look up. Shortly after that collaboration, we got into Tribeca and shortly after that Submarine came aboard as a sales agent and we got a distributor. The other great thing that happened at IFP Week was that I met with Amazon. They expressed interest in the film and we were able to begin discussion with them that came to fruition after Tribeca.

Filmmaker: Your film features numerous interviews with art dealers and art connoisseurs, both from that time period and in the present. What personally mattered most to me was how several artists, Penny Arcade and Clayton Patterson chief among them, were also featured. They represent the downtown New York art scene that, if not in existence today, prospers in Penny and Clay’s refusal to let their fellow artists fade into the past. What did their inclusion provide for your film?

Jacoby: Their inclusion was essential. For me, wanting to make a film that evokes a world, creates a background and environment that helps feel like the viewer is actually there, it was important to recruit genuine, downtown New York characters, and particularly ones who had a relationship with Richard and a history that paralleled him. They could speak to his experience in a mutual way. We didn’t want outsiders or critics who would judge him (or art dealers who interacted with him in a very different way). Carlo McCormick, although not an artist, was someone very much a part of that scene, and Mette Madsen, Richard’s former girlfriend, is also an artist and part of that community. She lived in the same building as Jim Jarmusch and was part of that scene.

Filmmaker: Was it important that your interview subjects represent a mix of NY artists/advocates who make this work along with the the art world that technically profits from it? That contrast feels like a constant throughout.

Jacoby: It was all about putting Richard in the context of the people who had working relationships with him and were part of his life. Each of the characters we interviewed helped us to track his story, his development and to show his rise and fall (and then second rise and fall) that he experienced in the art world. Some of those people were downtown colleagues and others were dealers or collectors who had relationships with Richard. Those were the people that he depended on. He turned to them for money, for help and for a place to stay. Each of those collectors had longstanding relationships with Richard that would run really hot and cold. He would love them one moment and then all of a sudden turn on them or they would turn on him. It went up and down and added to the drama of the story. It helps you understand the conflict and turmoil Richard was dealing with throughout his life

Filmmaker: Shadowman‘s first half serves as a retelling of Richard’s prolific career. With New York City serving as his canvas, his notoriety really kicked off in the summer of 1980 with the Shadowman paintings featured across every wall and alley in the city. It’s a creepy sight, one only accentuated by your archival footage’s depiction of it on celluloid. The material is at times scratchy and faded, and it grounds it in the decrepit seediness of 1980s New York. How did the film look of the archival material play a part in your documentary?

Jacoby: I started my career working in film, often in 16mm, which is what I think a lot of that footage was shot in. Some of it was actually very early videotape, i.e. the stuff with Richard painting the shadows on the streets. That was shot with in an early, portable video format, I believe. Then there was the wonderful footage of Richard in his studio where he’s painting some of his first horse rider canvases that we included in the movie. That was all shot on film.

I love film and the texture it has. I love when it shows the artifacts apparent from the printing process, the scratches that give it a kind of grittiness. And because it’s film, there’s this pristine underlying reality apparent, whereas the most sophisticated video can make it feel artificial. Film makes it feel real. I just heard that Steven Spielberg shot his new movie, The Post, on film because he wanted that real look to evoke the specific time period.

Filmmaker: Are you conscious of the visual shifts an audience makes when you toggle between film and digital video? There’s a contract between the archival footage and the newer footage you shot in 2009.

Jacoby: I mean, you deal with the realities of the technology you have available to you. I can’t afford to shoot on film today because it’s just too expensive a medium for most documentaries. However, the stuff that I shot in Richard’s studio, for example, never could have been shot on film. We used all available light in what was a very dark environment, and we had to focus the camera while we were “on the run,” sometimes having to switch to autofocus and pray that something in the image would be in range. We didn’t have time to focus the camera, and that would [be a disaster using film].

When we shot the primary interviews, I felt that they needed to feel contemporary. You should know that these people are being interviewed in the current day, discussing Richard, and that time has gone by. In that way, you try to be conscious and aware of the tools you’re using and how they affect the storytelling.

Filmmaker: In another instance of visually contrasting archival material, you incorporate Clayton Patterson’s home video footage of Hambleton’s early ’90s apartment, filled to the brim with dirty clothes, sex workers, dope users and paintings made in human blood. What did that footage, grungy as it was, offer your film narratively as well as visually?

Jacoby: When you describe those elements, you realize it’s an incredibly visceral experience. You feel like you’re in this unbelievable environment that most people will have never been exposed to and [can’t imagine] someone living like that. The visual format makes it feel more immediate.

Earlier you talked about the material of Richard in ’80s New York as a sort of grungy, seedy character, but it also has a sense of adventure and fun to it. To me, that was very much evoked in the scene where someone shone their car headlights on Richard, illuminating him painting the first shadows on the street. That footage had a fun, outlaw, adventurous kind of feel to it. Now contrast that with Clayton’s home movie footage in the drug house. That material is sad and desperate in a way that’s reflected in the chosen video format and Clayton’s style of shooting. It doesn’t romanticize the situation. A lot of people have made films about artists and drugs and depicted them very romantically. We were after showing something more realistic, the horror that comes into people’s lives while they’re struggling with addiction.

Filmmaker: It’s difficult to see the Shadowman paintings and not think of Banksy, a street artist your film briefly mentions. How do you feel about artists doing that kind of work today, and as extension, the documentaries that follow them?

Jacoby: It’s very interesting that this film is coming out at the same moment as Faces Places, the film Agnès Varda did with JR. We went over to London to film Steve Lazarides, who grew up in Bristol with Banksy and served as his manager and agent for many years, helping to create the worldwide phenomenon that was Banksy. I guess they had a split a few years ago, but for a long time they were partners, and Steve spoke to how Richard was one of Banksy’s great inspirations.

There’s a scene in our film where people are looking at Banksy’s work on the streets of New York, as he had come to the city a few years ago and had a few surprises. Every day a new Banksy piece was being discovered in a different neighborhood in New York City, and he was only in contact with one New York press person, Keegan Hamilton, who would receive a tip on where these pieces would show up next. Keegan was, at the time, with The Village Voice and now with VICE, and he had been in touch regarding Banksy’s desire to provide an homage to the originators of the the kind of art Banksy now makes. Richard was high on his list.

To answer your question on how I feel about this kind of art today: the big difference with Richard and all of his colleagues – and those who followed after him – was that he didn’t have it in him to play the game and work the dealers in a successful, organized fashion. Maybe it was because of his psychological problems or his addictions or whatever, but he, as Penny Arcade says in the film, never allowed the market to dictate what he was doing as an artist. It was never about making money. And while that’s not to say that he wouldn’t do a painting to sell so he could keep on living, he wasn’t altering his art because he thought it would advance his career. He was doing the work that was in him and needed to get out.

Banksy is a master salesman and a genius at using mass media to advance his reputation and add to the appeal (and price tag) of his art. He’s made himself millions and millions of dollars as an artist. That’s not something Richard was ever able to do or even thinking about doing.

Filmmaker: Is it important, as a filmmaker documenting an artist, to capture the essence and playfulness of the work itself? I’m sure you’re always trying to establish the correct tone for the story you’re trying to tell, but the film is also influenced by the tone of the given artist’s work. Do you attempt to find a balance between the tone of the work and the tone your film takes on?

Jacoby: You’re paying us a nice compliment. I think that’s what we were trying to do, to have the film make you feel connected to the spirit of the work. We were going for a feeling of spontaneity that was present in Richard’s art. There’s certainly a nostalgia for the punk era and ’80s New York now, and the idea was for Richard to evoke that world while also removing the illusion and hype of the nostalgia to show what it was really like. We wanted to evoke his world, to make you feel more connected to what it felt like to be there. As a documentary filmmaker, that’s what I’m always trying to do. Rather than comment on it, I want to help you relate to it and let you feel what it was really like.

Filmmaker: Several times in the film, Hambleton’s contemporaries Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat are noted as being the most sought after “street artists” of their time, and the best thing for their careers was that they died young. This interview is taking place a mere three weeks after Richard’s death at the age of 65. That’s noted in a title card that concludes your film, but how do you feel his death impacts the way audiences may view his work (and your film) now?

Jacoby: Well, he didn’t die young the way Basquiat and Haring did. Basquiat died at the age of 27 and Haring was 31. There was so little work that they were able to produce [in their young lives], and so the value of the work went up. Richard had thirty more years to work with then they did. I’m no art dealer and I can’t talk about the value of the work, but it’s apparent that more attention is being paid to Richard because of his recent passing and because this film is coming out. There is a feeling of “here was someone who had a really considerable contribution to art and who isn’t with us anymore, and so now let’s take a look at his work more seriously.”

One other sad note is that Richard died two days before the opening of a show at MoMA, “Club 57,” that includes one of his great early canvases. The original Club 57 was a small space downtown at 57 St. Mark’s Place and Richard, Basquiat, Haring, and other artists of the time often gathered there. While the show is still running at MoMA, Richard never got to see his work in the museum, although he knew the curators and knew his work was going to be included. It stands out as the only really large, impressive canvas in the show. Haring’s piece is a small piece of plywood with some scribbles and doodles on it and the Basquiat is an 8X11 piece of typing paper with some Xs and Os on it. Richard’s is a big, incredible canvas! It shows that he was an important figure early in the movement, and it’s sad that he didn’t live to see it.