Back to selection

Back to selection

“When the Design is Really Part of the Whole of a Film, the Film is Well Designed”: Production Designer Thérèse DePrez

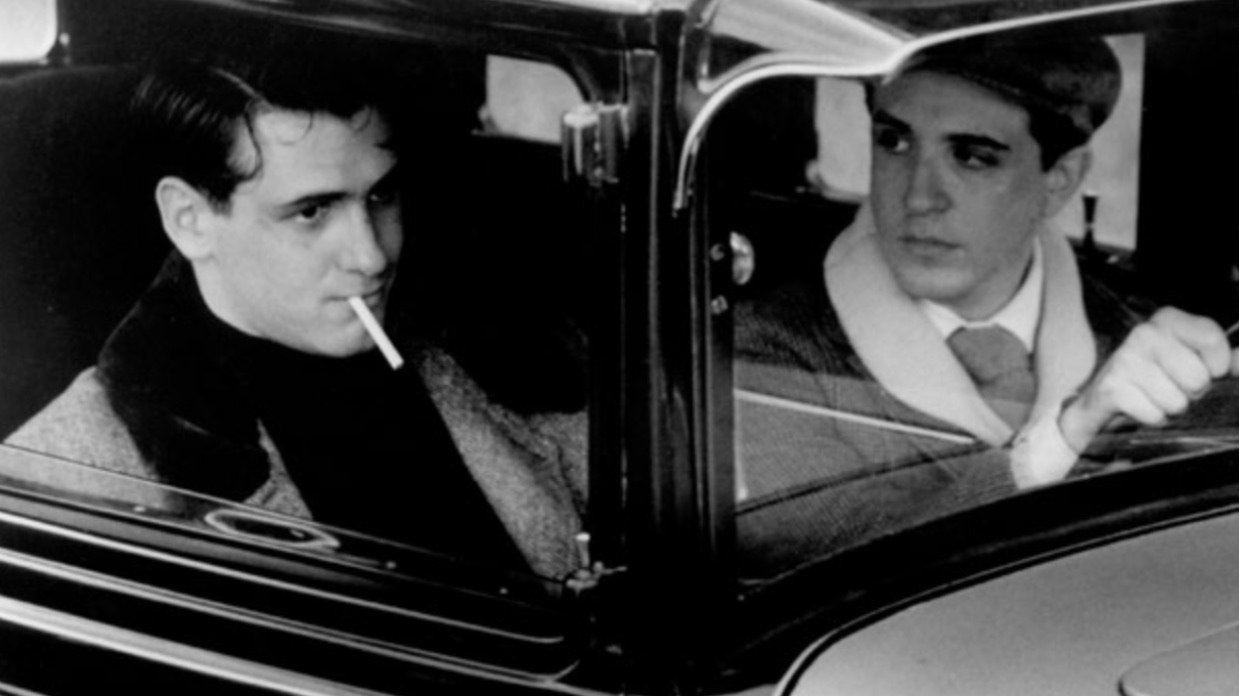

Swoon

Swoon The following profile of production designer Thérèse DePrez was written by producer Ted Hope for Filmmaker‘s Spring, 1994 issue, and is being rerun on the sad occasion of DePrez’s passing this week in New York.

After the standard art school stint, and the pay-your dues PA/grip/electric rigmarole, Thérèse DePrez nabbed her first designer gig on Tony Jacobs’s low-budget consumer/horror send-up, The Refrigerator, which sent her further down the blood-spewed path to art direct three straight-to-video horror pics. The creepy crawlers allowed DePrez to hone the “specialty prop” and set design skills she would later call on for Tom Kalin’s Swoon, Todd Haynes’s Dottie Gets Spanked, Steve Maclean’s David Wojnarowicz bio Postcards from America and Gregg Araki’s freshly-wrapped Doom Generation.

It’s no surprise she finds the directors Cocteau and Méliès her true inspirations for the way their films weave heavy conceptual design through the plot and characters’s s psychology. Dr. Strangelove, Bladerunner and Brazil, along with other breakthrough futurist films, are her “totems.” Laying down the law, she states that “when the design is really part of the whole of a film, [the film] is well designed. When one aspect of a film overshadows the rest, it’s a failure. A good designer will work with the other teams on a film to keep everything at the same level.”

“On Swoon,” DePrez continues, Tom Kalin and I selected an anchronistic design concept to bring the story into the present. Perhaps we should’ve pushed it even further. The budget for the film was very low, and I had no crew, which all helped to push the design to a stark minimalism and forced us to focus on individual objects as pieces of art, all the while keeping it within its period. Whereas 30 (Kalin’s Geoffrey Beene promo piece) was much more theatrical, playing on specific images from other films, like Blood of a Poet.

“I’ve been lucky to work with directors who are artistically inclined. I think a director should always hire a designer that has the same aesthetics and sees the script in the same way they do. I find that the directors I come to respect the most have stacks of research — photos, paintings, literature, films — when I first meet them… They needed to be that specific.

“Personality is the second most important to one’s aesthetics. The director is working so closely with the designer, the designer needs to have a personality that can put up with all the production entails — the budget and schedule constraints. They need to be someone who’s not going to break down, someone that has strength [along with] the aesthetic sense they were originally hired for.

“The conceptualization unfortunately begins with the budget, in addition to the script. I prioritize things in relation to color and lighting. Most of the films I’ve done are very stylized, and I’ve gone beyond the realism of the characters and their environments.

“I read through the script without stopping, and I have initial instinctual designs and concepts immediately; they tend to be the ones I stick with. They come to me for some reason. Then I read the script again for breakdown purposes.

“The relationship with the DP is equally important. I feel all my relationships are important. In prep I ask the DP the width of the shot, what lenses they are using, how much will be seen, how they’ll be lighting it, etc. I don’t want to design anything if it is not going to be seen or will go out of focus. I like to go over every shot in preproduction. It’s the inevitable last-minute changes that are frustrating, but it’s one of the reasons why I’m a designer who likes to be on set. I don’t want to be haunted at the dailies with the, ‘You didn’t tell me you were going to do that’ surprises.

“It’s really important that a designer be brought in early — particularly on a low-budget film — on the location selection process. A designer is going to be able to determine how a location fits in aesethetically, from an architectural and period point-of-view, far more than a location scout.”

Pressed for her dream job, DePrez quickly replies, “To design locations that have not yet been seen; a futuristic-type film is ideal. I live for the day that won’t have to be locked into such a tight budget — where I’ll only have to design and not have to design/artdirector/propmaster/build, etc. It’s compromising to have to do it all. I’d like the opportunity to just design.”