Back to selection

Back to selection

“Documentaries Are Less an Act of Creation and More an Act of Discovery”: DP Bob Richman on The Price of Everything

The Price of Everything

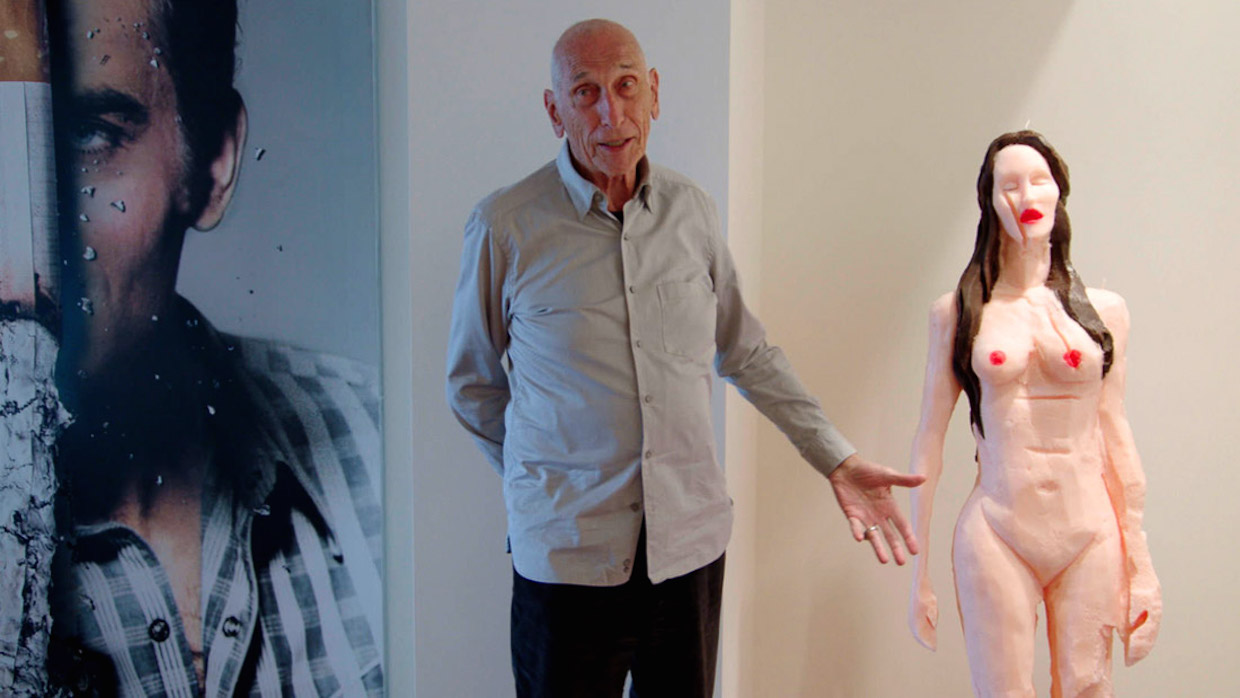

The Price of Everything Brooklyn-born DP Bob Richman began his career as a production assistant for Albert and David Maysles. He’s since gone on to shoot some of the most widely seen documentaries of the past 20 years: An Inconvenient Truth, Waiting for ‘Superman’, the Paradise Lost trilogy and Metallica: Some Kind of Monster, to name a few. His latest feature, The Price of Everything, is a vérité doc on the puzzlingly astronomical price of fine art. Richman spoke with Filmmaker ahead of the film’s Sundance premiere about his preferred camera for vérité filmmaking, reuniting with director Nathaniel Kahn (My Architect) and the essential importance of a good sound recordist.

Filmmaker: How and why did you wind up being the cinematographer of your film? What were the factors and attributes that led to your being hired for this job?

Richman: Nathaniel Kahn, the director of The Price of Everything, and I actually first met at Sundance in 1995, when a film I shot, Paradise Lost, premiered there. At the urging of a mutual friend and colleague, Andy Clayman, we went on to collaborate on his ground-breaking, Oscar-nominated film, My Architect. Nathaniel and I have continued to have a very special working relationship ever since so I think it was natural for him to bring me on to this film

Filmmaker: What were your artistic goals on this film, and how did you realize them? How did you want your cinematography to enhance the film’s storytelling and treatment of its characters?

Richman: I’m a vérité documentary cameraman, so for me the artistic goals and treatment of story and character almost never waivers from film to film. It’s not about cinematography or a “look;” it’s about feeling, about how I feel filming the action in front of me and how I’m reacting with the camera to best capture that feeling. I want the viewers to feel the same direct connection with the moment and the intimacy with the characters that I do, without any artifice filtering that experience. This is why it’s so important for me to be working with a director, like Nathaniel, who also wants to preserve that quality both during the filming and in the editing room. The ultimate goal is a film that transcends the film’s topic, whether it’s the art world, a fashion magazine or a murder trial, and reveals, through an honest portrayal of the characters coping with the challenges that life presents them, something universal about the human condition.

Filmmaker: Were there any specific influences on your cinematography, whether they be other films, or visual art, of photography, or something else?

Richman: My influences have largely been the great vérité pioneers of the ’60s and ’70s: D.A Pennebaker, Ricky Leakock and most of all Albert Maysles and David Maysles, who gave me my first job and taught me everything I know about vérité filmmaking.

David was not a cameraperson but his guiding filmmaking principles remain a huge influence on my camerawork. Robert Frank’s seminal book The Americans will always be a creative touchstone as are the photographic works of Henri Cartier-Bresson, Gary Winogrand, Josef Koudelka and Mary Ellen Mark. My influences in the narrative world include Vitorio De Sica, Yasujiro Ozu, Akira Kurosawa, Francis Ford Coppola, Martin Scorsese, the sumptuous lighting of Vitorio Storaro and Gordon Willis, and John Cassavetes’ Husbands, which manages magically to have the same sense of reality and immediacy as any documentary. The paintings of Edward Hopper, the music of John Coltrane and Jimi Hendrix, and, the humor of Lenny Bruce and Groucho Marx are also influences.

Filmmaker: What were the biggest challenges posed by production to those goals?

Richman: The biggest challenge in a film like this is not a cinematic one. It’s getting access to the right characters in the right situations and then developing trust. This process starts with the director in pre-production. Nathaniel is brilliant at this and on The Price of Everything we were extraordinarily lucky to have one of our producers, Jennifer Stockman, who also has a keen sense of who to film and whose connections to the art world gave us access to many of our subjects and locations. When I show up on the shoot with my camera and soundman, it’s my job not to screw up the delicate relationship established and eventually to help develop that trust until the subject feels perfectly comfortable being filmed. The way Nathaniel works, many of the scenes are a vérité and interview combination. We follow the subject around while they are engaged in an activity, like painting, or showing us something, and Nathaniel talks to them while trying to dig deep into their working or mental process. It’s always a revelation that if we do our job correctly each time, the relationships grow and our subjects allow us to see a deeper layer of who they are. There is a constant communication between Nathaniel and I during filming, much of which is non-verbal.

Filmmaker: What camera did you shoot on? Why did you choose the camera that you did? What lenses did you use?

Richman: For the last few years my rig has been the Arriflex Amira and the Canon 17-120 lens. My first camera was an Aaton and a Canon 8-64 lens. When shooting 16mm this was, in my view, the perfect handheld camera rig. It sat neatly on my shoulder and the lens gave me a wonderful wide to telephoto range. Over the years when switching to tape and then digital cameras with super 35 sensors, I’ve always looked for a rig that can give me that kind of ergonomics and lens range. I want the camera to become part of my body and a lens that allows me to go from a three shot to a close up of someone’s eyes without moving an inch.

The Amira, besides having a beautiful sensor, has all the buttons in the right place and so you can make changes in filtering, iso, and color temperature on the fly while shooting. It has a sharp viewfinder, and the eyepiece and shoulder pad move easily so you can find the perfect balance to accommodate the weight of the lens. The Canon 17-120 is a true cine lens with beautiful glass and has a short rotation for both the zoom and the focus rings that are perfect for handheld work. I can zoom with my thumb and index finger while focusing with my pinky at the same time (the lens comes with a micro-force but I prefer the human touch to the mechanical). All these qualities allow me to be comfortable in intimate situations and to deliver footage with enough wide and tight shots to make it easier for the editor to cut a true vérité scene. Most importantly, these qualities help me to shoot as I see and how I see expresses how I think and feel.

Cartier-Bresson said, photographs “are made with the eye, heart and head.” For the handheld cinematographer I would like to add the back and the legs and some bicep thrown in. I would be very happy to lose 10 pounds from my 25 pound rig and still have the balance, lens range and beautiful Arri sensor.

Filmmaker: Describe your approach to lighting.

Richman: If possible, I always use available light or I try to simply enhance the available light with a minimum amount of light fixtures to keep our footprint small and giving me the ability to shoot as close to 360 degrees as possible.

If I’m shooting an interview I keep it simple and natural and usually go for a soft single source look. I try to build in some contrast. Every face is like a unique landscape and although I often use just one or two lights, where I place them and whether I use negative or positive fill, can mean all the difference in the world.

Filmmaker: What was the most difficult scene to realize and why? And how did you do it?

Richman: This is the third year in a row that I’m answering these same questions. They are geared more toward fiction cinematographers than documentary cinematographers. This is the one question that stumps me every year. It implies that scenes are designed beforehand and that there is some technical solution the DP devised to implement that vision and make the scene work. I am quite sure that is what happens on a fiction film. Documentaries are less an act of creation and more an act of discovery. That’s what makes shooting them so thrilling to me. The question I would ask is, what was the most pivotal, or important, or even exhilarating scene and how did you cover it? These scenes aren’t planned and they present themselves suddenly without any warning. You not only have to realize its importance, you have to capture it in the moment with all its information and emotional verisimilitude. One scene that comes to mind is when Larry Poons visits an Upper East Side auction house that presumably had an old painting of his and they wanted him to verify it. This scene came up unexpectedly while we were shooting Larry at his loft. When we arrived, the executive in charge of contemporary art led us into a quiet room. The work of art turned out to be an unfinished and discarded canvas for one of Larry’s famous dot paintings. At some point Larry started to hotly explain to the gallery executive how when he stopped making these dot paintings back in the ’70s because he was ready to move on artistically, his gallery had dropped him and the art world discarded him. He continued to pursue art at its highest level without the affirmation of dealers and critics. This is the crux of Larry’s story and is a central theme in the film, exploring who decides what art is worth.

I had Larry in a tight profile and could widen out to get Paula, his wife, who was looking on with pride. The gallery executive, who was a bit taken aback by Larry’s almost defiant outburst, is about 6’3 and Larry is only about 5’5 so it was almost impossible to get a good wide shot. I wanted to get a close-up of the executive’s slightly startled face so the editor will have some sort of cut-away to work with. I was torn, I didn’t want to take the camera away from Larry who was quite compelling and I knew that this moment would be over in a flash. There are no retakes, no second angles so I did my best, and of course, I failed miserably. The scene was so rich that the editor, in this case the wonderful Sabine Kryayenbuehl, was able to make it work and since the viewers of the film were not there, and I was lucky to have nailed it enough, they won’t have any idea how much I failed. That’s how it is, one string of failures after the next, but it’s all about how badly you fail because, let’s face it, you can never completely capture it. I try to do my best, on a wing and a prayer.

One final word about the unsung heroes of vérité filmmaking, the soundman. No great vérité film could be made without them. The soundman on this film, Eddie O’Connor, has worked with me on many films including My Architect. We are a team, and we act as a unit. Eddie not only moves seamlessly with me and gets great sound he also helps to set a non-intimidating tone on set. The reality is that a vérité scene can work with bad picture but not bad sound.

Filmmaker: Finally, describe the finishing of the film. How much of your look was “baked in” versus realized in the DI?

Richman: Once again this is a question for a fiction film. If it truly is an act of discovery you can’t really plan a look because you have no idea how the film will evolve. The look, of course, has a lot to do with my handheld camera work. In each scene, I react as I come to it, try to make the best of what is in front of me and then hope to improve it in the color correct. It’s almost impossible and can be counter productive to try to give a consistent look except for the way it’s shot, which goes back to trying to capture the feeling and truth of the moment. What would take much longer to describe are the conversations I had with Nathaniel before each scene. He would tell me what he thought was going to be important in terms of content and visually and I would try to incorporate that information into my coverage. The conversations we had after shooting were even more extensive. We would try to figure out what we got right and wrong, and what we learned. We would then take those ideas to the next shoot. It’s a very collaborative and exhilarating way to work. Our approach to the material is constantly evolving as we move forward on our journey of discovery. These conversations are what truly shaped the “look” of the film.

TECH BOX:

- Camera: Arriflex Amira

- Lenses: Canon 17-120 cine lens

- Lighting: Available Light

- Processing: Digital