Back to selection

Back to selection

“The Edit Room Became a Kind of Experimental Laboratory”: Editor Nyneve Laura Minnear on 306 Hollywood

306 Hollywood

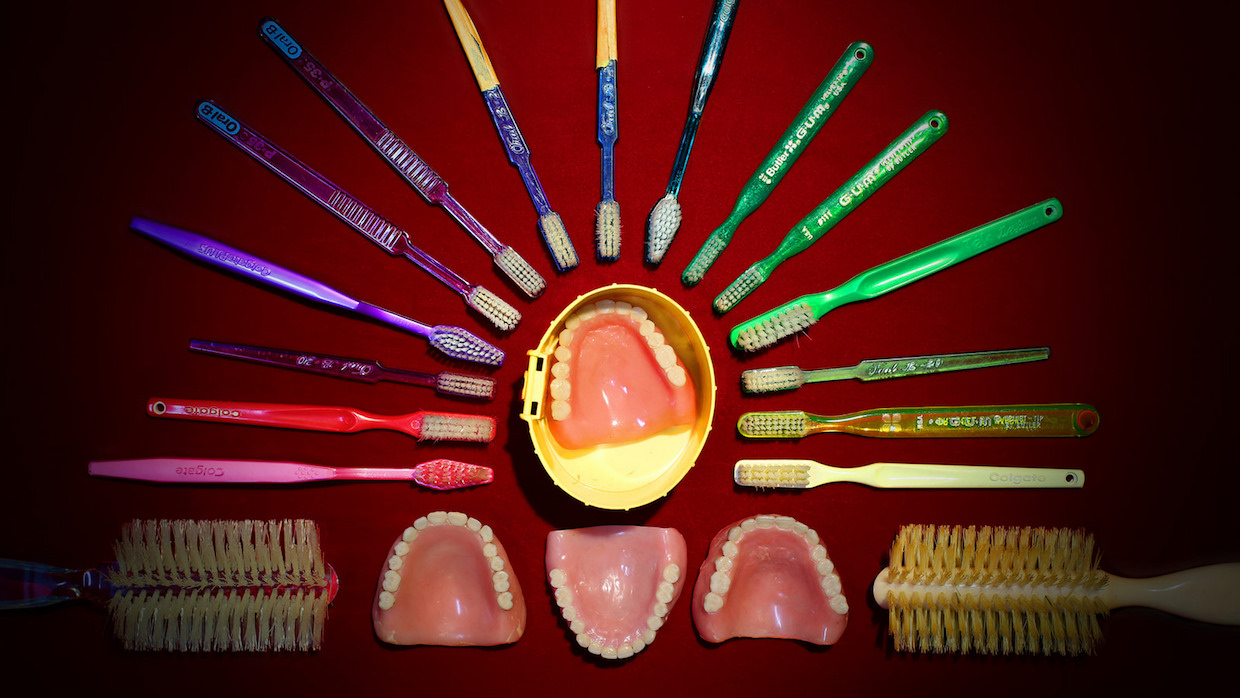

306 Hollywood As Scott Macaulay wrote in our 25 New Faces profile of 306 Hollywood directors Elan and Jonathan Bogarin last year, “In 2001, the pair — who together run the production house El Tigre Productions — began shooting their grandmother, Annette Ontell, in the Hillside, New Jersey house she resided in for 71 years. When she died in 2011, the Bogaríns decided, says Jonathan, ‘to keep the house and transform everything there into a film.’ The result is the beautifully strange 306 Hollywood, ‘a kooky, imaginative film,’ he says, that uses ‘a maximalist language of fiction film, art, dance and myth in order to draw in an audience like a Hollywood film — but one with no budget and a crew of two.'” Here, editor Nyneve Laura Minnear goes long on the unique challenges of this production.

Filmmaker: How and why did you wind up being the editor of your film? What were the factors and attributes that led to your being hired for this job?

Minnear: I’ve had the good fortune to be friends with Jonathan and his wife Yuko for years, and Jonathan and I had always joked about how amazing it would be if our schedules and projects would align to be able to work together someday. Eventually, I cut one of Jonathan and Elan’s shorts for the Whitney Museum and it was clear we really had amazing chemistry in the edit room, both personally and creatively. Many of my previous films have focused on one strong and usually quite eccentric character and I think this experience was the main attribute they were looking for in an editor — someone with strong long-form storytelling experience who could help give shape and depth to Grandma Annette and the larger themes they wished to explore.

Filmmaker: In terms of advancing your film from its earliest assembly to your final cut, what were your goals as an editor? What elements of the film did you want to enhance, or preserve, or tease out or totally reshape?

Minnear: The primary goals of the edit were to create a non-fiction film that could be as entertaining and engaging as a fiction film and to push the boundaries of how we see and represent reality. One of the trickier elements was figuring out what role Elan and Jonathan would play as characters. Although it had always been deeply personal, they were reluctant, as most directors are, to be in their own film. Who wants to see a nostalgic film about someone’s grandmother who isn’t famous and who didn’t really do anything in her life all that remarkable? So we used a light touch with their presence at first and the edit often ventured into impersonal “essay” territory at times. But once we understood how crucial and active their exploration needed to be and that it really was the excavation that would push the story forward, we teased their role out in various ways. We felt intuitively that they needed to be seen physically on camera every so often, so we played a lot with how that might look. For example, we added shots of them to the open 1970s driving material that weren’t originally there as a way to anchor their presence more deliberately. And we slowly came to understand the language of how to show them physically going through the house, which would appear at various points in the film.

Jonathan and Elan also have brilliant editing timing that’s been honed from their years of making shorts for museums and art collections. The sharp punctuation from scene to scene, creating visual surprises, was very much inspired by their experience and sensibility. This was teased out more and more as the edit progressed. Of course when it came to the interviews with Annette, it was important that we preserve the right balance between her charm and humor, capitalizing on her comic relief, and the more philosophical moments when we wanted her to dispense her advice, but without becoming too sentimental.

Filmmaker: How did you achieve these goals? What types of editing techniques, or processes, or feedback screenings allowed this work to occur?

Minnear: The process of editing this film was unlike anything I’d ever been involved with. It was truly collaborative in the sense that all three of us were “editing,” regardless of who was physically in front of the computer at any one time. The borderlines of writing and scripting and editing and storyboarding and shooting blended and morphed, responding to the needs of the moment. At one moment it was more important that we nail the visuals to understand what the scene or transition could be, at another it was more important to script out their narration, and yet another it was most important to see the bigger picture of where the story was headed before we could move forward.

What was truly unique for me was how the edit room became a kind of experimental laboratory. All non-fiction film editing is an unknown process of experimental trial and error: finding new associations, discovering new themes and uncovering new depths within the material in front of you. But this process was more akin to what I would imagine an animation studio to be like; the way to tell this story was completely invented. There was a freedom of play here to create entire worlds from both what was and wasn’t already in the footage. For example, we might have an idea for the emotional tone of a scene and have a sense for where it needs to come, but not understand visually how to express it. So we made draft after draft after draft of sketches with any images already available and placeholder cards to probe how to draw out the emotional depth we were going for, and this would inform how to reshoot something. Once Elan and Jonathan would reshoot it, these images would lead to discoveries for something else to take shape. So it was a back and forth between the edit room and shooting at the house that led us down avenues one couldn’t necessarily script out from the beginning. On the other hand, some scenes like the shredding of documents were very much scripted from the beginning and shot intentionally without changing very much once it became clear what emotional beat was needed at that particular point in the story.

The criticality we each brought to our daily feedback sessions was the most brutal and exhilarating process I’ve ever experienced in the edit room. First, Jonathan and Elan being siblings set a tone of intimacy that can allow for cutting straight to the point. And each one of us being extremely opinionated, the debates were heated at times. To create this kind of work was to invest quite personally in each sketch, each draft, and yet we had to take “not taking things personally” to whole new levels for it to work. The advantage is that there was the space for drafts of scenes to be horrible most of the time until they eventually worked — it was actually the expected starting point and there was no problem with it. From our daily experiments we would draw out ideas of what was working or could work in the future. We truly made better work this way.

What was also new for me is that this was the first film I’ve ever worked on where we didn’t have feedback screenings. We trusted that if we got the film to a place that all three of us loved, we would stand behind it no matter what.

Filmmaker: As an editor, how did you come up in the business, and what influences have affected your work?

Minnear: I came to filmmaking in my late 20s. My previous background was in biology/zoology, languages, dance and percussion, and at the time I was looking for something that would bridge the arts and sciences. I started out in production on more journalistic and science-based documentaries for PBS (Frontline and NOVA), but the minute I met editors and saw an edit room I fell in love. When I moved to NY, I knew I wanted to focus on character-driven verite documentaries, but I didn’t have much experience. The most important moves I made were to consistently turn down well-paying TV production work to take poor-paying AE jobs on indie docs that would allow me to be in the world I truly wanted to be in. I eventually met wonderful editors and directors who believed in me and referred me for projects I wasn’t so qualified for, and first-time directors who graciously paid me enough to scrape by and on whose projects we learned together.

I also travelled quite a bit before coming to filmmaking and spend a lot of time reading and engaged in philosophy. I devour writings on consciousness and reflections of artists and scientists and big thinkers. This has led me to be become just as interested in character portraits as experimental film. A broad range of interests, life experiences and insatiable curiosity are probably more important than anything else when it comes to learning how to tell a good story in the edit room. It’s the wellspring of new ideas. That, and watching and being inspired by a ton of films.

Filmmaker: What editing system did you use, and why?

Minnear: We used FCP7 primarily because the archival footage of Annette’s interviews and some of the other supplementary material was ingested many years earlier and Elan and Jonathan had already been experimenting for quite some time. Even though it wasn’t ideal technically once eventually introducing new 5D and C300 material, it didn’t make sense to shift gears to another system in the middle of the process.

Filmmaker: What was the most difficult scene to cut and why? And how did you do it?

Minnear: This was without a doubt the most difficult edit process I have ever been involved with. We could write volumes about the process and at the same time not be able to say very much except “who knows how we came up with that.” But one section in particular that was among the hardest starts with funeral director Sherry Anthony’s appearance in Annette’s bedroom to the appearance of the portal in the kitchen and Jonathan following Annette “out.”

In a sense there are two instigating moments in the film, Annette (Grandma’s) death and the moment Jonathan and Elan as characters decide to take the “other” path, the one most people don’t choose to go down – to stop the momentum of getting rid of everything and explore if there indeed still is life left in the house. From early on in the edit, we knew we needed some good reason for why they decide to keep the house. While the language of fairy tales and myth was always a guide and inspiration, it took some time to stumble upon these two devices. And it took upwards of who knows, maybe 50 iterations to get it to work. I’m a great fan of Joseph Campbell and The Hero With A Thousand Faces and loved the idea that the “custodians of the past” could be guides to lead Elan and Jonathan deeper down the rabbit hole, as well as the idea that a “portal” could play as the threshold they cross into another world.

Most of our early versions were just too confusing however, or too contrived, or the language and visuals too abstract. First, we needed to make Sherry Anthony’s appearance out of nowhere work, to feel eerie, on the borderline of reality and fantasy. That eventually came from both the exact combination of images — the right kind of first image of Sherry in the mirror, Elan “looking up” at a strange noise — and then trying out what felt like hundreds of combinations of what exactly Anthony says and when. Then we realized the moment they sense something strange is going on had to come immediately before Sherry, just a note of it. This was a huge part of the process. There was no clear method through the difficult and unknown sections. We just kept trying to adjust things over and over until something felt right. Often times one single image could make all the difference and crack a scene. Other times it was the right word at the right time in combination with the image. In this sense I imagine the process is much more akin to fiction film editing. The hybrid nature though would be that sometime they would just go back to the house and reshoot a couple of shots to see if that would help. It became clear early on that there was no way they could sell the house until we were picture locked. What if one more image would be the key to making an entire scene work?!

Regarding the portal, we had upside down images available before we knew where to use them. It was just something Jonathan and Elan played with in the field. The key to cracking this scene was understanding the concept that Annette was “calling” them. It wasn’t enough that a strange portal appears and “how cool. It’s a door to another world!” This felt contrived and unrelatable. Annette’s beckoning preserved the emotional arc, and then from there working with a writer really helped us craft the nuance of the narration to pull it all together.

Filmmaker: Finally, now that the process is over, what new meanings has the film taken on for you? What did you discover in the footage that you might not have seen initially, and how does your final understanding of the film differ from the understanding that you began with?

Minnear: It’s interesting, I think the broader potential of this film and what we dreamed it would be became apparent to us after the first few months of discussions and sketches. I worked on the project off and on for nearly two years and the vision didn’t really change, as it often does in documentary edits. In this case it just deepened and finally came to life. Of course the most important part was that Elan and Jonathan recognized for years before starting the edit that the interviews with their grandmother had something special going on. One of the keys to my own understanding of what kind of a story we might have on our hands came early on in the edit with the excavation of her interviews. It truly felt like an excavation. Looking for patterns in what she said, like the very Jewish-sounding names of her friends who had died, and her quirkiness in describing mundane things. She really became alive for me more and more throughout the process.

I didn’t go to the actual house for the first time until the very end of the edit. By then both Annette and the house were so vivid and almost mythical in my mind that it was an incredibly surreal experience. I wanted to touch everything, even the toilet paper in the bathroom with the Scotch label from the ’70s was a source of wonder. My final understanding and what the final film shows me is really more about the beauty of the creative process, that such a film, a crazy idea, could even be possible. That the normal can truly be elevated to the magical simply by shifting one’s angle of perception. I feel beyond fortunate to have joined the ride.